Protestors demonstrate outside the office of Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker during his fireside chat at the Wisconsin State Capitol February 22, 2011 in Madison, Wisconsin. (Photo by Eric Thayer/Getty Images)

Protestors demonstrate outside the office of Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker during his fireside chat at the Wisconsin State Capitol February 22, 2011 in Madison, Wisconsin. (Photo by Eric Thayer/Getty Images)

Hiding out at a secret location in Illinois, Wisconsin state Sen. Kathleen Vinehout ends every media interview with the same warning: Republican Gov. Scott Walker’s attack on public employee unions is overshadowing another part of his budget plan that could shred the state’s health care safety net.

The governor’s proposal, a “budget repair” bill that would strip most public employees of their collective bargaining rights, would also allow the Walker administration to make potentially drastic changes in health programs with little legislative oversight. Officials say it could help tackle a looming two-year $3.6 billion deficit. But, the result, Vinehout predicts, is that “large numbers of people will lose BadgerCare,” a component of Wisconsin’s Medicaid program.

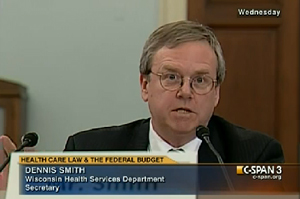

Taking the lead in revamping health programs for the poor would be Dennis Smith, Wisconsin’s new health secretary. A mild-mannered bureaucrat and head of the federal Medicaid program under President George W. Bush, he’s known within policy circles for staunchly conservative views and stinging critiques of President Barack Obama’s health care law.

Under Walker’s plan, Smith could reshape critical aspects of Wisconsin Medicaid and potentially strip tens of thousands of people from the rolls. He’d also be directed to ask the federal government for permission to go further.

In the process, Smith could chart a course for other Republican-led states seeking to reduce deficits by paring Medicaid. And he could emerge as a national leader in the right’s resistance to the new health law, an increasingly important issue in the lead-up to the 2012 elections.

Smith

Still, Smith faces some hurdles. The health law makes an additional 16 million people eligible for Medicaid, a joint state-federal program, beginning in 2014 and bans states from dumping most people who are now covered.

Nonetheless, an analysis by the independent state Legislative Fiscal Bureau says Wisconsin could drop about 70,000 higher-earning adults from Medicaid without getting permission from Washington.

Smith is already edging into the national spotlight in part thanks to House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan of Wisconsin. A day after Smith was confirmed as health secretary, he was called before the panel to testify on how the health law will hurt the state’s residents.

“Expanding Medicaid under the current framework doesn’t make sense,” he told Kaiser Health News in late 2009 as the law was being debated. “You’ve got to give states flexibility.” (Smith couldn’t be reached for comment for this story.)

Just over a million people in Wisconsin are enrolled in Medicaid, at a cost of more than $6.5 billion in 2009, the latest year available. That year, the federal government picked up almost 70 percent of the cost, but the share will decline when stimulus funds dry up this summer. Walker says Medicaid costs are at the root of half of the projected deficit.

Currently, most major Medicaid changes must be cleared by the full Wisconsin legislature. But, under Walker’s bill, Smith’s health department could make those changes through an emergency rule-making process without legislative approval. The Joint Committee on Finance would have 14 days to veto the changes. But critics say the new rules mean Smith and Walker wouldn’t have to present detailed plans to the public.

What Smith comes up with “may be brilliant,” says David Reimer, a former state budget official who is now director of Community Advocates Public Policy Institute in Milwaukee. “It may be awful. But we don’t know.”

Smith, an Illinois native, was head of the federal Center for Medicaid and State Operations from 2001 to 2008. He also worked on Capitol Hill and ran Virginia’s Medicaid program. Before becoming Wisconsin’s health secretary, he was a senior fellow at the conservative Heritage Foundation and also worked for Utah-based Leavitt Partners, a consulting firm set up by Michael O. Leavitt, former secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services.

Leavitt says Smith left the consulting firm because “he wanted to use his experience in a laboratory where his vision could be demonstrated. There’s no question that if he’s able to put it together and make it work, others will follow him.”

Still, while it’s clear that Walker and Smith want to tackle Medicaid, the question is: What’s their plan? The budget bill outlines some likely changes, but also gives Smith leeway to make broader ones that aren’t yet clear.

In the past, Smith has consistently argued that Medicaid should focus only on the poorest people (Wisconsin covers individual adults earning nearly $22,000), and should rely on private managed-care programs to restrain costs. He also has promoted charging recipients higher co-pays to try to dissuade them from seeking unnecessary treatments.

Critics, such as Judith Solomon, an analyst with the liberal Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, say Smith has long advocated policies that could hurt the poor and undermine the intent of Medicaid. Opponents also cite a 2009 paper published by Heritage that seemed to advise states to drop out of Medicaid altogether.

But Robert Moffit, a senior fellow at Heritage who brought Smith to the think tank in 2008, says while “there’s no question Smith is a real conservative,” he’s thoughtful and open to new ideas.

As head of the federal Medicaid program, Smith issued a record number of waivers that allowed states to experiment – including increasing the use of managed care and allowing states to find new ways to pay doctors and hospitals.

“How many newly insured individuals gained health insurance under the Bush administration because of our waivers?” Smith said in the 2009 interview. “Instead of getting credit for that, we got criticism” from liberals who wanted Washington to control the programs more tightly, he said.

The Obama administration is likely to resist the kind of changes Smith will likely want to make in Wisconsin. Though federal Medicaid officials would not specifically comment on Wisconsin, they indicated that the types of policies suggested in Walker’s bill – such as barring people who are likely eligible for Medicaid from receiving services before being formally enrolled – could pose problems.

But Leavitt, Smith’s old boss, says economic problems have become so severe that something has to give. “Health care policy has always been driven by human compassion,” he says. “We can’t lose it, but we are now dealing with a new factor.”