Among the young people known as “Dreamers,” Ever Arias belongs to a select group.

Of the roughly 700,000 unauthorized immigrants who have temporary but tenuous protection from deportation, only 99 are in medical school. Fewer still have made it to their final year.

Arias is one of them and, come June, will start his medical residency — the on-the-job training he needs to become a doctor.

What’s not clear is whether he’ll be allowed to finish and, ultimately, practice in the United States.

“We’re at the mercy of the government at this time,” said Arias, 27, who will graduate this May from Loyola University Chicago’s Stritch School of Medicine.

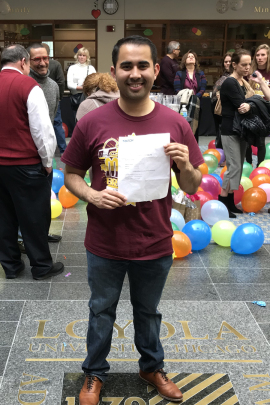

Last Friday, Arias got great news. On Match Day, when 31,000 medical students nationwide found out where they will be trained as residents, he learned he would be heading to Southern California, where he was raised. His three-year residency will be in internal medicine, and his goal is to practice in underserved communities that need bilingual doctors, he said.

But at this pivotal moment in his medical career, Arias must focus both on his academic future and his legal one. In September, the Trump administration announced it would end the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, setting off an ongoing political and legal battle that could overshadow the careers of immigrant doctors in training.

The tug-of-war has left Dreamers — the name given to people brought illegally into the U.S. as young children — wrestling with apprehension and uncertainty. The stakes are particularly high for those like Arias, who have bet everything on professions that require high-cost educations and several years of training. The end of the DACA program could mean the end of their careers in the United States.

Ever Arias celebrates on Match Day, after learning he would be headed to Southern California for his medical residency training. (Photo courtesy of Ever Arias)

“The biggest fear I have is that one day everything I’ve worked for will be taken away,” Arias said.

President Barack Obama created DACA in 2012. The program allows qualified young people to obtain temporary work permits, which Arias and other Dreamers need to complete their training and advance in their careers.

The future of DACA is tied up in courts. Earlier this year, federal judges in California and New York temporarily blocked Trump’s move to terminate the program, and his administration is appealing.

For now, Dreamers can reapply for the status every two years, but there’s no guarantee how long that will last.

“Without DACA, there is very little possibility that medical students will be able to fulfill their profession,” said Betzabel Estudillo, of the California Immigrant Policy Center. This is of particular concern in the medical field where there is an urgent need for a “robust and diverse workforce,” she said.

Ignacia Rodriguez, immigration policy advocate at the National Immigration Law Center, called Arias and other Dreamers “pioneers.”

“They’ve had this ambition before DACA was around and they’ll continue to work towards it even if DACA were to be taken away,” she said. “But they deserve stability.”

After months of applications and interviews, Arias was excited that he “matched” with his first choice, a residency program in Southern California. He declined to name the institution, citing the uncertain political situation.

Arias, who was born in Mexico and brought to the U.S. at age 6, grew up in Costa Mesa, Calif. He graduated from the University of California-Riverside in 2012 and, after a two-year break, started medical school.

When the Trump administration announced its plan to rescind DACA last year, Arias was in the middle of applying to residency programs. He worried that they might reconsider whether to continue accepting DACA recipients because they could run the risk of losing their trainees midstream if DACA were eliminated.

But some residency programs aren’t letting the uncertainty cloud their decisions.

“We want programs to be able to choose from the best and brightest and to be able to select applicants who would be best suited for their institutions and communities, regardless of status,” said Atul Grover, the executive vice president at the Association of American Medical Colleges, which represents medical schools and teaching hospitals.

Residency programs take a risk with every student they admit, not just Dreamers, added Sunny Nakae, the assistant dean for admissions at Loyola’s medical school. “The threat that looms over DACA obviously adds a more foreseeable risk,” she said. But “there’s no guarantee that anybody … is going to finish.”

Arias toyed with the idea of waiting a year before applying; he thought maybe the political climate would cool by then.

“But we decided it was now or never,” Arias said of himself and the other Dreamers in his graduating class.

He recently applied to renew his DACA status, he said, and is trying to simply focus on “the craft of learning medicine,” not the turmoil surrounding the immigration debate. If DACA were eliminated, he and other recipients would lose their status at different times, whenever their two-year terms ended.

Before DACA, people without permission to live and work in the U.S. couldn’t get medical residencies because they didn’t have work authorization, Nakae explained.

Raquel Rodriguez, 30, was one of the few undocumented students who started medical school before DACA was created.

Rodriguez, who was born in Mexico City and raised in San Diego, is a second-year family medicine resident in Southern California. She also declined to disclose the name of her residency program.

Rodriguez received her undergraduate degree from Harvard University in 2009. But because she had neither immigration papers nor DACA, her academic counselor discouraged her from applying to medical school, explaining that she wouldn’t be able to secure a residency spot, she said.

She applied anyway, and in 2011 she started medical school at UCLA.

“I applied, but didn’t think I’d get in, and then I did and I had no idea how I was going to pay for it,” she recalled.

Medical school is expensive — the median in-state tuition at a public medical school was about $37,000 for the 2017-18 academic year, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges.

Rodriguez’s friends from Harvard helped her pay for her first year. Then in June 2012, DACA paved the way for other financial opportunities. By patching together scholarships and loans, Rodriguez got herself through her remaining years of medical school.

She will finish her medical residency training next year. She also has a master’s degree in public policy and hopes to find a job that combines both disciplines. She’s still not sure what that will look like, but she knows she wants to give back to low-income communities.

So does Arias. Members of his family didn’t have health insurance because of their legal status, so he’d like to serve populations who also struggle with limited access to coverage and care, he said.

“I see the role I can play in my community,” he said. “I don’t want that to be stripped away from me.”

This story was produced by KFF Health News, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.