Aetna, one of the nation’s largest insurance companies, will remove a key barrier for patients seeking medication to treat opioid addiction. The change will take effect in March and apply to commercial plans, a company spokeswoman confirmed, and will make it the third major insurer to make the switch.

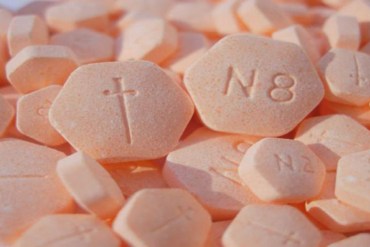

Specifically, Aetna will stop requiring doctors to seek approval before prescribing particular medications ― such as Suboxone ― that are used to mitigate withdrawal symptoms, and typically given along with steady counseling. The insurance practice, called “prior authorization,” can result in delays of hours to days in getting a prescription filled.

The change comes as addiction to opioids, which include heavy-duty painkillers and heroin, still sweeps the country. More than 33,000 people died from overdosing on these drugs in 2015, the most recent year for which statistics are available. And it puts Aetna in the company of Anthem and Cigna, which both recently dropped the prior authorization requirement for privately insured patients across the country. Anthem made the switch in January and Cigna this past fall.

Both companies took the step after facing investigation with New York’s attorney general, whose office was probing whether their coverage practices unfairly barred patients from needed treatment. They made this adjustment as part of larger settlements.

It sounds like just a technicality ― a brief delay before treatment. But addiction specialists say this red tape puts people’s ability to get well at risk. It gives them a window of time to change their minds or go into withdrawal symptoms, causing them to relapse.

“If someone shows up in your office and says, ‘I’m ready,’ and you can make it happen right then and there ― that’s great. If you say, ‘Come back tomorrow, or Thursday, or next week,’ there’s a good chance they’re not coming back,” said Josiah Rich, a professor of medicine and epidemiology at Brown University and doctor at Providence-based Miriam Hospital, who frequently treats patients with opioid addictions. “Those windows of opportunity present themselves. But they open and close.”

As these major carriers drop the requirement, treatment specialists hope a trend could be emerging in which these addiction meds become more easily available. In New York, for instance, the attorney general’s office will be following up with other carriers who still have prior authorization requirements, an office spokesperson said. The office would not specify which carriers it will next examine.

Meanwhile, though little research pinpoints precisely how widespread this coverage practice is for drugs that treat opioid addiction, experts say it’s a fairly common practice.

“Just think of any big health insurance company that hasn’t recently announced they’re doing away with this, and it’s a pretty safe bet they’ve got prior authorization in place,” said Andrew Kolodny, a Brandeis University senior scientist and the executive director of Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing, an advocacy group.

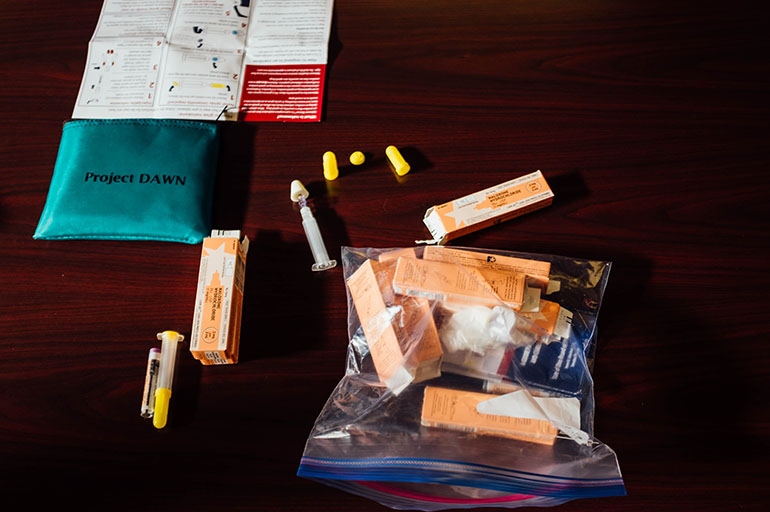

Aetna will stop requiring doctors seek approval before prescribing particular medications such as Suboxone. (Wikimedia Commons)

How does the problem manifest? Take Boston Medical Center, located in a region that’s been particularly hard hit by opioid addiction. Doctors there wanted to launch an urgent care center focused on this patient population. Less than a year old, the program’s treated thousands of people.

But prior authorization requirements have been intense, said Traci Green, an associate professor at Boston University’s School of Medicine and deputy director of the hospital’s injury prevention center. To help people get needed care ― before it was too late ― the center hired a staffer devoted specifically to filling out all the related insurance paperwork.

“It was like, ‘This is insanity,’” Green said, adding that “navigating the insurance was a huge problem” for almost every patient.

But defenders of the requirement maintain that such controls have value. Insurance plans using prior authorization may view it as a safeguard when prescribing a potentially dangerous drug. “[It’s] not a tool to limit access. It’s a tool to ensure patients get the right care,” said Susan Cantrell, CEO of the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy, a trade group.

Other large insurance carriers ― such as United Healthcare and Humana ― list on their drug formularies a prior authorization requirement for at least some if not all versions of anti-addiction medication. A spokesperson from Humana said the practice is used “to ensure appropriate use.”

Also, though, it is generally agreed that the practice is used to control the prescribing of expensive medications. Per dose, the cost of these drugs varies based on brand and precise formulation, but it can go as high as almost $500 for a 60-pack dose, which can last a month.

Regardless of intent, critics say, those extra forms and hoops do make it more difficult for patients in need to get these medications ― ultimately, they say, doing more harm than good.

“If you would like a physician to not do a particular treatment, put a prior authorization in front of it,” Rich said. “That’s what they’re used for.”

Meanwhile, addiction treatment advocates and health professionals are hoping to build on what they see as new momentum.

Earlier this month, the American Medical Association sent a letter to the National Association of Attorneys General, calling for increased attention to insurance plans that require prior authorization for Suboxone or other similar drugs.

Minnesota’s attorney general has written to health plans in the state, asking they end prior authorization for addiction treatment. New York has also heard from other states interested in tackling the issue, the attorney general spokesperson said. And another project, called Parity Track, is soliciting complaints from consumers.

They’re arguing based on a requirement that insurance plans, thanks to so-called “parity laws,” must cover addiction treatment, and cover it at the same level as they do other kinds of health care.

The prior authorization requirement “doesn’t meet the sniff test for parity,” said Corey Waller, an emergency physician who chairs the American Society of Addiction Medicine’s legislative advocacy committee. “It’s a first-line, Food and Drug Administration-approved therapy for a disease with a known mortality. Every other disease with a known mortality ― the first-line drugs are available right away.”

But the justification for legal cases like New York’s could get weaker. The 2010 health law, which lawmakers are working to repeal, included requirements that mental health and addiction treatment be considered an “essential health benefit.” If that disappears, robust coverage for addiction could be less widely available, several noted.

Meanwhile, the stakes are substantial, Rich said. He recalled a patient who was taking a version of buprenorphine ― the active ingredient in Suboxone ― who had a brief relapse with heroin. That led to complications in the paperwork for renewing his prescription for treatment.

“Now he’s out of the office, in the street, using more,” Rich said of that case. “Incumbent upon [effective treatment] is the ability to get people started right away. If there’s prior authorization? It’s infuriating.”