As she surveyed patients’ charts, Nancy Romeo, a medical review auditor at a hospice company, was surprised by the resilience of those supposedly near death.

One patient admitted to hospice care in 2002 was still healthy enough in 2007 to stroll around his yard at home, she found. Another patient received hospice care for four years before the company for which Romeo worked, SouthernCare, determined she was not dying. “I looked at charts every day, and almost every chart was inappropriate,” said Romeo, a nurse.

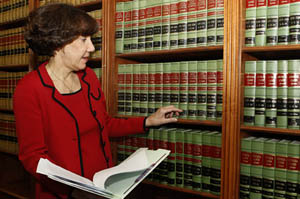

Nancy Romeo, a medical review auditor at a hospice company, was surprised by the resilience of many of the patients and filed a suit claiming the company had fraudulently enrolled patients. (AP Photo for KHN/Butch Dill)

Nancy Romeo, a medical review auditor at a hospice company, was surprised by the resilience of many of the patients and filed a suit claiming the company had fraudulently enrolled patients. (AP Photo for KHN/Butch Dill)

In 2007, she filed a whistleblower lawsuit against SouthernCare claiming that the company had fraudulently enrolled patients in hospice. Eventually, the government obtained a $24.7 million settlement in the case. SouthernCare, based in Birmingham, Ala., and one of the nation’s largest for-profit hospice companies, admitted no wrongdoing, and officials declined comment for this article.

Over the 28 years that Medicare has reimbursed providers for hospice services, it has been praised for giving critical medical and emotional support to dying patients and their families. When properly used – that is, at the very end of life – hospice care also has saved the government money. Providing dying patients with palliative care in their own homes, or in a hospice facility or nursing home, is far less expensive than continuing to order up futile medical treatments, studies have shown.

Indeed, advocates say more patients should be receiving hospice services earlier in the course of their illness. The median time spent in hospice care now is just 17 days.

But as hospice has moved into the mainstream – it is now serving 1.1 million Medicare patients a year – concerns about excessive costs and misuse have mounted.

Four in 10 Medicare beneficiaries now use the hospice benefit before they die. Patients agree to forgo treatments aimed at prolonging their lives, but can receive pain-relieving medication to ease the symptoms of a terminal illness, as well as attention from nurses, social workers and others.

Medicare’s bill for hospice care rose to more than $12 billion in 2009 from $2.9 billion in 2000. Although the benefit is intended for patients who have no more than six months to live, 19 percent now receive hospice services for longer, according to the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, or MedPAC, an independent congressional oversight panel. In 2009, 10 percent of patients remained in hospice beyond seven months. Medicare pays a flat fee ranging from $147 to $856 a day, depending on the level of care, whether a hospice actually provides services or not.

Financial Incentives

A primary concern of MedPAC is that this payment method encourages hospices to seek out patients likely to live longer. For-profit hospices in particular tend to have longer-staying patients, studies have shown.

“The financial incentives do in fact dictate behavior,” said Eugene Goldenberg, a research analyst for BB&T Capital Markets who follows the hospice industry. “It’s a lucrative business, at least under the current reimbursement system.”

In response, Medicare has adopted a restriction: It won’t pay for hospice beyond six months unless a physician or nurse practitioner visits the patient and attests that his or her condition is still terminal. But this requirement, part of the health care law passed last year, has provoked a backlash.

Hospice operators say sending a doctor or nurse practitioner out to see every patient at the six-month mark is too expensive. Presently, most hospices rely on registered nurses to see patients and then relay information back to the office.

“This face-to-face visit is a way to limit the length of people staying on hospice, and it probably will increase the number of people who get discharged,” said Dr. David Casarett, an associate professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and chief medical officer at the university’s Philadelphia-based hospice. “But will we be discharging the right people? I’m not sure.”

But given the financial and political pressures facing Medicare, government officials are concerned that hospice care may be misused. The inspector general of the Department of Health and Human Services looked at one fast-growing segment – hospice patients in nursing homes – and found hospices routinely failed to document that those patients belonged in a hospice or that they were getting the care to which they were entitled. The inspector general is now investigating unusual patterns of hospice stays.

Evidence produced in a series of lawsuits, too, suggests that hospices may need more careful oversight.

A regional vice president at Trinity Hospice, a now-defunct chain based in Texas, “strongly encouraged” employees to “find a way” to keep patients as long as possible, according to a 2005 internal report uncovered in a whistleblower lawsuit.

In 2006, the government obtained a $12.9 million settlement from another national chain, Odyssey Healthcare, after a former manager there said she was fired for trying to get the company to discharge patients who did not meet Medicare’s eligibility rules.

Both companies settled the cases out of court and did not admit wrongdoing. Odyssey was subsequently bought by Gentiva Health Services, and a company spokesman had no comment on the settlement.

Dementia’s Unpredictability

One of the main reasons for longer hospice stays is the increasing prevalence of patients with diseases, like dementia, that follow sometimes unpredictable paths. For instance, Alzheimer’s patients are three times more likely than cancer patients to stay in hospice beyond six months, MedPAC data show.

In 2009, Duane Chirhart, a retired airline pilot, questioned the cost of his aunt’s hospice care while she was in a nursing home in Minnesota. For more than two years, the nursing home had been taking care of most of her needs. At the same time, a hospice company billed Medicare $4,252 a month for its services, which included short visits by outside nurses.

“The employees who visited her were really caring people,” he said, “but there only were four or five hours a month when they were actually there.” Chirhart canceled the hospice service. His aunt, who has Alzheimer’s, is now 88 and still alive.

When the humorist Art Buchwald went into a hospice in February 2006, he expected to die within weeks of kidney failure. But his kidneys kept working, and Buchwald made national news when he quit hospice after five months. He died the following year.

To allow for greater flexibility, Congress ended the strict seven-month time limit imposed when the benefit was created. Now hospice care can continue indefinitely so long as the hospice said the patient is still likely to die within six months.

“To some degree, the growth in the number of beneficiaries and the duration of stays is the result of conscious policy changes,” said Jonathan Blum, deputy administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Alexander Horvath, who is 85 and has dementia, is in his eighth month of care provided by the Jewish Social Service Agency Hospice, a nonprofit in Rockville, Md. His wife, Jacqueline, believes that he is receiving excellent, cost-effective care. The hospice has taken steps to prevent bedsores, for instance, by replacing his mattresses with special ones that help keep lesions from developing. “I want him to be as happy and comfortable as long as he possibly can be,” she said.

But the profit motive in hospice has become a greater concern as for-profits hospices have expanded. They now account for half of Medicare certified hospices. A study in the Journal of the American Medical Association published in February found 6.9 percent of patients tended by for-profit hospice providers remained for more than a year, while 2 percent of those in nonprofits did.

“Objectively if patients are in hospice more than a year, it kind of suggests that based on current hospice eligibility criteria they have been enrolled too early in the course of their terminal illness,” said Dr. Melissa Wachterman, the study’s lead author.

J. Donald Schumacher, president of the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, based in Alexandria, Va., said longer stays are a good development, because the full benefit of hospice can’t be realized in just the final days of life. He said a hospice’s ownership type does not influence the nature of care provided, and credits hospices for enrolling patients earlier in their declines. “Hospices have gotten better and more sophisticated in marketing their services to patients whose illness are moving from chronic disease into terminal illness,” Schumacher said.

But some fear that hospice companies have become too aggressive. “There are rival companies trying to get people to sign up for who will care for them until they die,” said Lloyd Peeples, an assistant U.S. attorney who led the government’s case against SouthernCare. “I had no idea there were companies fighting over patients, just like telephone companies fighting over whether to sell you an iPhone or a Blackberry.”

jrau@kff.org