Once again, the majority of the nation’s hospitals are being penalized by Medicare for having patients frequently return within a month of discharge — this time losing a combined $420 million, government records show.

In the fourth year of federal readmission penalties, 2,592 hospitals will receive lower payments for every Medicare patient that stays in the hospital — readmitted or not — starting in October. The Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, created by the Affordable Care Act, was designed to make hospitals pay closer attention to what happens to their patients after they get discharged.

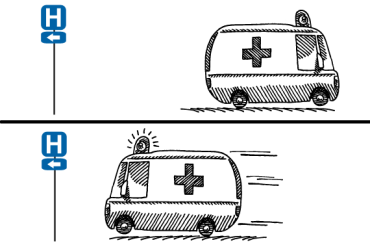

Illustration by Andrew Villegas/istockphoto

Since the fines began, national readmission rates have dropped, but roughly one of every five Medicare patients sent to the hospital ends up returning within a month.

Some hospitals view the punishments as unfair because they can lose money even if they had fewer readmissions than they did in previous years. All but 209 of the hospitals penalized in this round were also punished last year, a Kaiser Health News analysis of the records found.

The fines are based on readmissions between July 2011 and June 2014 and include Medicare patients who were originally hospitalized for one of five conditions: heart attack, heart failure, pneumonia, chronic lung problems or elective hip or knee replacements. For each hospital, Medicare determined what it thought the appropriate number of readmissions should be based on the mix of patients and how the hospital industry performed overall. If the number of readmissions was above that projection, Medicare fined the hospital.

The fines will be applied to Medicare payments when the federal fiscal year begins in October. In this round, the average Medicare payment reduction is 0.61 percent per patient stay, but 38 hospitals will receive the maximum cut of 3 percent, the KHN analysis shows. A total of 506 hospitals, including those facing the maximum penalty, will lose 1 percent of their Medicare payments or more.

Overall, Medicare’s punishments are slightly less severe than they were last year, both in the amount of the average fine and the number of hospitals penalized. Still, they will be assessed on hospitals in every state except Maryland, which is exempt from these penalties because it has a special payment arrangement with Medicare.

These lower payments will affect three-quarters of hospitals or more in Alabama, Connecticut, Florida, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Virginia and the District of Columbia. KHN found that fewer than a quarter of hospitals face punishments in Idaho, Iowa, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota and South Dakota.

Most of the 2,232 hospitals spared penalties this year were excused not because Medicare found readmissions to be sufficiently infrequent, but because they were automatically exempted from being evaluated — either because they specialized in certain types of patients, such as veterans or children, because they were specially designated “critical access” hospitals, or because they had too few cases for Medicare to accurately assess.

The readmission penalties are not the only fines hospitals face this year. As it did last year, Medicare is also giving out bonuses and penalties based on a variety of quality measures. The government has not yet announced those, but they also begin in October. Those financial incentives will total about $1.5 billon. Medicare will also punish hospitals with high rates of infections and other avoidable occurrences of patient harm.

The KHN analysis found that four hospitals have received the maximum readmission penalty every year. Two are in Kentucky: Harlan ARH Hospital, which is in the heart of the Appalachian coalfields, and Monroe County Medical Center in Tompkinsville. The other hospitals are the Livingston, Tenn., Regional Hospital — also in Appalachia — and Franklin Medical Center in Winnsboro, La. None of the hospitals immediately returned phone calls Monday.

Hospitals have been lobbying both Medicare and Congress to take into account the socio-economic background of patients when assessing readmission penalties. They argue that some factors for readmissions — such as whether patients can afford medications or healthy food — are beyond their control.

The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, which advises Congress, has recommended altering the readmission penalties. The National Quality Forum, a nonprofit that Medicare looks to when creating quality metrics, is examining whether socio-economic factors should be included when calculating readmission measurements as well as other barometers of hospital quality. But that experiment will take two years to complete.

“Hospitals should not be penalized simply because of the demographic characteristics of their patients,” Sens. Joseph Manchin III (D-W.Va.) and Roger Wicker (R-Miss.) wrote last week in the Journal of the American Medical Association. The senators have introduced a bill to consider socio-economic factors when calculating the penalties.

Their essay, co-written by Dr. Andrew Boozary, a health policy analyst, pointed to a study that found safety-net hospitals were nearly 60 percent more likely than other hospitals to have been penalized in all of the first three years of the penalties. Hospitals with the lowest profit margins were 36 percent more likely to be penalized than those in better financial shape, the essay said.

In regulations released Friday, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reiterated that it would not unilaterally make such changes in the program, noting that some safety-net hospitals have been able to keep their readmission rates low.

“While we appreciate these comments and the importance of the role that sociodemographic status plays in the care of patients,” the agency wrote in the rule, “we continue to have concerns about holding hospitals to different standards for the outcomes of their patients of low sociodemographic status because we do not want to mask potential disparities or minimize incentives to improve the outcomes of disadvantaged populations.”