Cody Pedersen and his wife, Inyan, know that in an emergency they will have to wait for help to arrive.

When Inyan, 34, was preparing to give birth to her two youngest children, doctors scheduled her to have C-sections in a hospital rather than having her come in to give birth after she went into labor. In January, Cody was stabbed in the neck. It took an ambulance two hours to arrive.

Though he survived, Cody knows that unless he and his family go themselves to seek care, which is often hours away by car, they’re unlikely to receive it.

Cody, 29, and his family live in Cherry Creek, a Native American settlement within Cheyenne River Indian Reservation in north central South Dakota. The reservation is bigger than Delaware and Rhode Island combined, but in Cherry Creek there is no general store, no gas station and few job opportunities. A 17-mile gravel road in Cherry Creek connects to a better road which eventually leads to Eagle Butte, the largest town on the reservation, and home to just over 1,300 people. That’s where the closest doctors are.

When Cody runs out of gas money, he has to pay $40 to a neighbor to take him to the health center in Eagle Butte. But he can’t even do that before lucking out and securing an appointment, calling at 7 a.m. on the same day he wants to see a doctor. Clinics like the one Cody goes to do not allow patients to schedule appointments in advance. And it affects their everyday lives: Their 11-year-old daughter Makrista missed school for two weeks because they can’t get a doctor’s note to vouch that her head lice has gone away. And, the family said they can’t get the note because the clinic in Cherry Creek has been closed for weeks.

Before the 1950s, most Native Americans lived in reservations or near them. Then, with support from the federal government, many started moving to large cities, looking for employment opportunities and better education. Today, more than half of Native Americans live in urban areas.

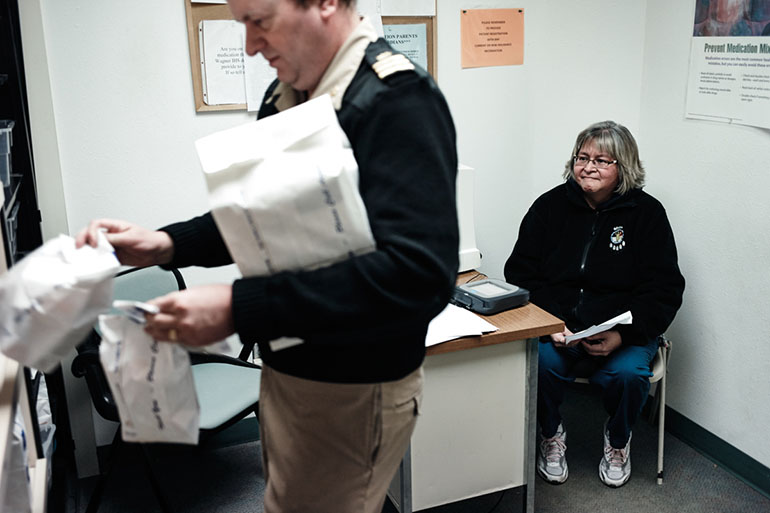

The federal government is obligated by law to provide medical care to American Indians and Alaska Natives, and it does it through the Indian Health Service, an agency of the Department of Health and Human Services. There are also tribal-run health centers set up on reservations. And 20 states have Urban Indian Health Programs, which receive IHS funding to provide medical services and support to American Indians who don’t live on reservations.

But there are still significant gaps in care, both on the reservation and in town. The IHS is chronically underfunded. It receives a set amount of money each year to take care of 2.2 million native people — no matter how much care they may need. On the reservation, IHS facilities often don’t have services that people elsewhere expect, such as emergency departments or MRI machines. And those limited facilities can be hours away by car. In town, reaching care is easier, but clinics also don’t have enough funding to meet all of the health needs of the community. And people can’t get the free drugs they are entitled to through the IHS anywhere but an IHS facility.

Donna Keeler is executive director at South Dakota Urban Indian Health, which has been providing health services to the American Indian population since 1977. Keeler said her clinics in Sioux Falls and Pierre receive federal grants, but unfortunately, a federal prisoner has a larger health care budget allocated to him than an urban American Indian does.

In 2013, Indian Health Service spending for patient health services was $2,849 per person, compared to $7,717 for health care spending nationally, according to a report from the National Congress of American Indians.

Keeler says most of her clients are the poorest of the poor, and typically have more serious health problems than the general public, including higher rates of diabetes, injuries and liver disease. In other states, American Indians with low incomes can sign up for expanded Medicaid. But South Dakota lawmakers haven’t expanded Medicaid coverage to low-income adults, leaving thousands of people, most of them urban, poor American Indians, without health coverage.

Gov. Dennis Daugaard, a Republican, has left the door open to a special legislative session this year in which lawmakers could consider a Medicaid expansion proposal, but even consideration of such a proposal isn’t guaranteed. If South Dakota did expand Medicaid, it would give clinics like the one Keeler runs additional funding, since the Medicaid reimbursement rates are higher than what IHS provides.

Still, even without Medicaid expansion, the Urban Indian Health clinic is an improvement for patients like Joe Marrowbone, Cody Pedersen’s brother. Marrowbone moved out of Cherry Creek and off the reservation partially to get out of the cycle of poverty prevalent there, he said. It was an added bonus that access to health care for his family also dramatically improved when they moved.

Marrowbone works as a janitor at a religious school in Sioux Falls. He and his family don’t have to travel from the reservation to get health care they need, and that makes a big difference. The Sioux Falls clinic location of Urban Indian Health is much closer to his home than it would be if he lived in Cherry Creek, and there’s also the option of getting care at a local hospital. As a result, the family rarely has to wait long to get the care they need. Instead of worrying about where his health care is coming from, Marrowbone can focus on a new goal: trying to adopt his niece, Savannah, after her mother died.

Not only is the health care available to Native Americans in South Dakota underfunded, management of patient records also hampers their care.

Jami Larson is a resident nurse at Urban Indian Health in Pierre. She said she is frustrated that none of the systems, among the Indian Health Service, tribal-run clinics or the Urban Indian Health Programs share patient data with each other. Each clinic has its own records that are often duplicated in different facilities as people enter the system, and as a result, those patients who don’t keep up with their own records often have to repeat immunizations or lab work.

For Larson, herself an American Indian, the year and a half that she’s spent as a nurse at the clinic in Pierre has allowed her special relationships with her patients.

She said that care for them would improve if the clinics, hospitals and doctors serving American Indians worked together. For now, Larson is leaving her own mark the best she can: On many days, you can find her visiting patients to make sure they’re on track and, through a federal program, she even goes food shopping with some to help make sure they’re eating food that will keep them as healthy as possible.

This story and photo essay were produced through a collaboration between Kaiser Health News and NPR.

Photographer Misha Friedman says he tries “looking beyond the facts, searching for causes, and asking complex and difficult questions.” His work has been featured by many media organizations, including NPR, The New Yorker, Sports Illustrated, Der Spiegel and GQ.

KHN’s Andrew Villegas contributed to this report.