Just as people are finding their bearings in a post-Affordable Care Act world, the health insurance market in Washington is on the brink of another upheaval.

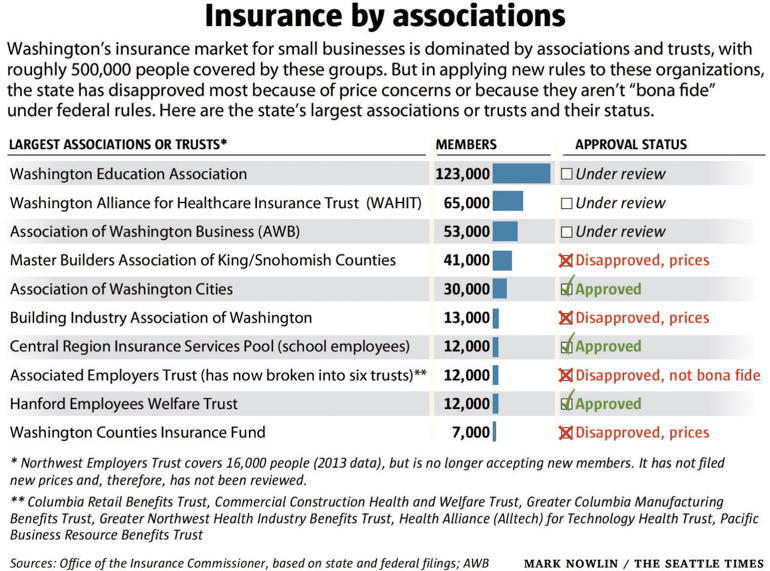

For 20 years, small businesses in the state have relied heavily on associations and trusts to provide coverage for their workers. These groups had cheaper prices than insurance sold on the open market, allowing them to become the dominant players, with roughly half a million of the state’s residents covered by these plans.

Now Insurance Commissioner Mike Kreidler, citing federal changes under the ACA, has rejected the majority of the state’s roughly 64 association and trust plans, saying they don’t comply with the new rules.

Kreidler said the changes will create a fairer, more stable marketplace in the long run for small-business coverage. Based on an Office of the Insurance Commissioner analysis of association plan prices for 2015, some employees are getting a raw deal, the commissioner said, with older workers sometimes paying eight times more than younger workers, and women of childbearing age paying higher rates, too.

Association proponents say the system is popular and works well, and they’ve challenged Kreidler’s policies, arguing that he has no legal power to disapprove their plans. Even those who don’t entirely object to Kreidler’s overhaul say the rollout of the rules and the review of the plans have been a disorganized, ad hoc mess.

As a result, health-insurance coverage for many small employers and their workers hangs in limbo — though most people likely don’t even know it.

“They are the innocent victims here,” said Sean Corry, a Seattle insurance broker with dozens of clients with association plans. “It’s all very irritating. I can’t tell our clients what’s going to happen. I can’t tell them they can keep their plan” a whole year.

Small businesses have traditionally had two insurance options: the small group market, which is open to everyone, or associations and trusts. (This year a third option became available statewide, small business insurance sold by the state-run Washington Healthplanfinder exchange, but few have signed on.)

In 1995, the Legislature created special rules for associations and trusts, allowing employers with 50 or fewer workers to buy “large group” insurance through the organizations. It meant the associations didn’t have to follow small-group rules, a provision that allowed price variation from employer to employer. The associations could charge a business with sick workers higher rates, essentially forcing them out, while keeping the prices lower for everyone else.

Washington’s rules created a market for small businesses dominated by associations and trusts — perhaps more so than in any other state.

But while associations thrived, the small group market, which cannot vary prices according to someone’s health, became much smaller and more expensive. Kreidler has warned that with so much “bad risk” — employers with sicker workers — in the small group pool, it could become unviable.

“If you want to have a stable market, you have to make sure plans aren’t cherry-picking the market,” Kreidler said. The commissioner, first elected in 2000, has over the years tried to stop the associations from such “cherry-picking.” He didn’t succeed.

Then came the ACA.

Dozens of plans disapproved

The 2010 ACA includes rules for insurance marketplaces, and those, in combination with additional instructions from the federal government, have led Kreidler’s office to apply a two-part test to associations and their plans to determine if they’re operating legally.

First, the association must have been formed for a purpose other than simply selling insurance, and its members must work in the same industry, such as farmworkers, restaurants or aerospace employees. A group meeting this criteria is deemed a “bona fide” association.

The second test determines whether the association is selling insurance plans at an appropriate rate. The plans can’t charge more for sick people or women, and they are limited as to how much more they can charge older workers than younger ones.

So far, only nine plans have cleared both hurdles. Nineteen failed the bona fide test and 22 were denied because of their rates. Two trusts that were disapproved are fighting the Office of the Insurance Commissioner (OIC) through administrative hearings, and one of them also filed a case in federal court.

One of those the office denied was the Master Builders Association Health Insurance Trust, which covers approximately 1,400 companies and 40,000 workers and their families in King and Snohomish counties.

The trust tried to meet the new rules, cutting up to 12 percent of its member companies to clear the bona fide bar, said Jerry Belur, CEO of EPK & Associates in Bellevue, which administers the trust. In January, Belur learned his trust was denied because of its prices.

“We were surprised and a bit disappointed because of our close working relationship with [Kreidler’s] office and the steps we had taken to meet the requirements in order to operate like we have for 20 years,” Belur said. The organization has not challenged the decision on legal grounds.

“We see this as one more step and are hopeful that the OIC will embrace our desire to continue to collaborate,” he said.

Impact on workers

Associations with disapproved plans have 90 days to appeal the ruling, and the employees they cover still have their insurance. If an association doesn’t appeal, the OIC asks that the group contact the agency, which can help move people to new coverage. That could include moving to another association, to the small group market, or to the state’s insurance exchange, either in the small group or individual market.

“We’ll wind up working with them so there will be a reasonable transition,” Kreidler said. “We’ll work to minimize the impact on individuals.”

An additional 13 plans await the office’s ruling; two are from the Association of Washington Business’s HealthChoice program, which insures 53,000 people.

While the AWB plans have not received the office’s approval, Jeff Gingold, an attorney representing association health plans including the AWB, said there is no legal requirement for Kreidler to sign off on their product.

Kreidler “has gone way beyond his constitutional authority, his legislative authority, even beyond his own rule making,” Gingold said. “Clearly the ACA has changed a lot of things in the health-care market, but in this particular area, Kreidler has been extremely vague as to what in the ACA has made this change.”

What may lie ahead

Gingold defends the association plans as a good deal for employers and employees, and he points out that 90 percent of enrolled employers renew their AWB coverage each year. If customers felt ripped off, Gingold said, they’d take their business elsewhere.

“Who is [Kreidler] protecting here?” he asked.

While experts are split over which side will prevail in the fight over the regulations, many agree that if the new rules survive, the associations will not.

“I think the association plan market that you saw in Washington, absent a court intervention, will not be there [in the future],” said John Conniff, a Tacoma-based attorney specializing in insurance regulatory compliance.

What would that mean for small businesses? As with other ACA-driven changes, some people would lose plans they liked and see their rates go up while others could get better deals. It would create a system that was more equitable between the associations and the small-group market.

“It’s a good thing to have everybody in the same pool and everybody plays by the same rules,” said Corry, the Seattle broker.

When it comes to insurance, if someone is getting a great deal, “it comes at the expense of somebody else,” Kreidler said. The new rules will help level the playing field.

“The ACA has been the ladder we needed,” he said, “to get that start.”