The Affordable Care Act brought health insurance to 5.5 million women over the past two years, but many women still tell of unmet health care needs that could pose risks for them or future pregnancies, a new report finds.

Researchers from the Urban Institute and the March of Dimes Foundation underscored the ACA’s long-term potential to improve health care for women in their child-bearing years, 18 to 44. The report was released Tuesday.

The health law, in addition to making insurance available to more women, also established maternal and newborn care as essential benefits for all health plans. They must also provide free preventive services, such as gynecological exams, and free supplies such as breast pumps.

Past studies have shown that costs prevent women from getting necessary medical care when they lack insurance, and that women who get services before and between pregnancies can improve their health and that of their future children.

“They’re getting the coverage they need and that’s the first step,” said Cynthia Pellegrini, senior vice president of public policy at the March of Dimes Foundation. The foundation funded the report as a first effort to monitor the health law’s impact on maternal care and birth outcomes.

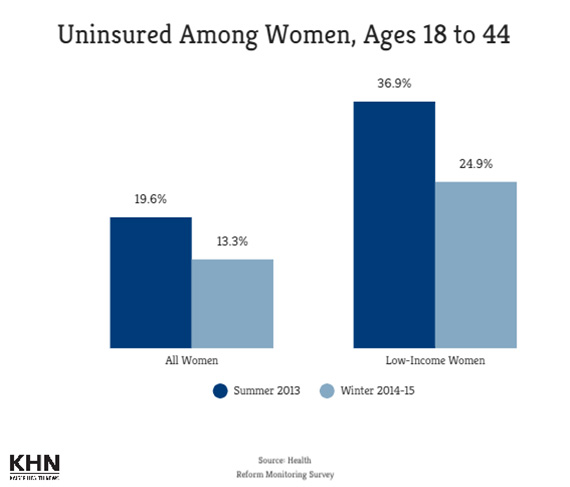

Researchers drew on data from the Health Reform Monitoring Survey, a quarterly online survey that is monitoring the ACA’s impact before federal survey data is available. It is funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Urban Institute.

The rate of uninsured women in their childbearing years dropped to 13.3 percent in winter 2014-2015 from 19.6 percent in summer 2013, representing an increase in coverage for 5.5 million women, the report said.

Other changes: Smaller shares of women overall reported problems paying family medical bills and having unmet needs for care because of cost than in the previous year. Both trends also held true for low-income women.

Other changes: Smaller shares of women overall reported problems paying family medical bills and having unmet needs for care because of cost than in the previous year. Both trends also held true for low-income women.

Despite signs of progress, the report said more remains to be done. Low-income women in states that did not expand Medicaid under the ACA did not achieve the same gains as low-income women in expansion states.

Almost a quarter of low-income women in their childbearing years remained uninsured last winter. Nearly half of low-income women – and almost four in 10 overall — reported an unmet need for care due to cost last winter, despite improvement on that issue since 2013, the report said.

Health care postponed for financial reasons could suggest that women who can buy insurance – instead of going on Medicaid – are choosing high-deductible plans under the health law. Those charge lower premiums but require users to first meet an annual deductible – and pay thousands of dollars for health care services themselves – before insurance kicks in for subsequent services.

“You’d have a high psychological concern about cost, no question about it. You’d also have a reluctance to see a doctor,” said David Newman, executive director of the Health Care Cost Institute, a nonpartisan nonprofit.

Another possible explanation for a woman missing needed care is the expenses associated with taking time off work if she is an hourly employee and possibly paying for transportation and childcare.

“For low-income women without great benefits, there are all sorts of issues that stop them from getting to the doctor. Access to insurance isn’t going to alleviate those other problems,” said Atul Grover, chief public policy offer at the Association of American Medical Colleges.

The challenge for future health care enrollment periods will be reaching more minority and low-income women, said Claire Brindis, a professor of health policy at the University of California, San Francisco.

“We’re still at the beginning of a major upheaval,” she said.