The Baltimore health system put Robert Peace back together after a car crash shattered his pelvis. Then it nearly killed him, he says.

A painful bone infection that developed after surgery and a lack of follow-up care landed him in the operating room five more times, kept him homebound for a year and left him with joint damage and a severe limp.

“It’s really hard for me to trust what doctors say,” Peace said, adding that there was little after-hospital care to try to control the infection. “They didn’t do what they were supposed to do.”

Pushed by once-unthinkable shifts in how they are reimbursed, Baltimore’s famous medical institutions say they are trying harder than ever to improve the health of their lower-income neighbors in West Baltimore.

But dozens of interviews with patients, doctors and local leaders show multiple barriers between the community and the glassy hospital towers a few blocks away.

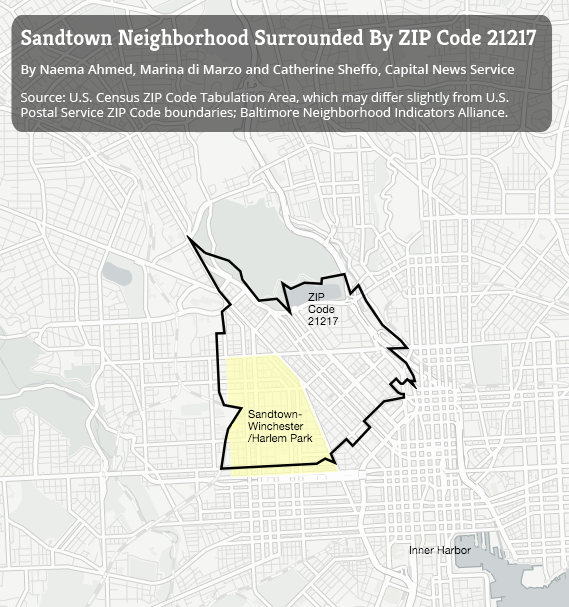

Reporters from Kaiser Health News and the University of Maryland’s Philip Merrill College of Journalism spent much of the fall in and around Sandtown-Winchester, a Baltimore neighborhood where violence flared last year after Freddie Gray was fatally injured in police custody.

Residents say they have little more confidence in the medical system intended to heal them than in the criminal justice system intended to protect them.

It’s really hard for me to trust what doctors say.

Even though his accident happened in 2004, Peace says he cannot view doctors and hospitals with anything less than deep suspicion.

“They almost let me die,” he said.

As with so much else, there are two Baltimores when it comes to health. One population is well off and gets the best results from elite institutions on the city’s west and east sides, the University of Maryland Medical Center and the Johns Hopkins Hospital.

The other is a poor minority that gets far less, even as it uses hospital services at higher-than-average rates. One indicator: The typical Sandtown resident lives a decade less than the average American.

“They come in with a great service, but they don’t have relationships with people in the community,” said Louis Wilson, senior pastor of New Song Community Church in Sandtown, a small wedge of about 5,000 households. “They want the people in the community to come in and respect them, but they don’t respect the people in the community. It does not work. It just doesn’t.”

The gap is more than the cultural distance between lower-income African-Americans and the wealthier practitioners, often of other ethnicities, who treat them, although that’s a part, Wilson said. It’s about insurance that is still unstable, confusing and perceived as expensive despite the health law’s recent expansion of Medicaid for low-income patients.

The gap is more than the cultural distance between lower-income African-Americans and the wealthier practitioners, often of other ethnicities, who treat them, although that’s a part, Wilson said. It’s about insurance that is still unstable, confusing and perceived as expensive despite the health law’s recent expansion of Medicaid for low-income patients.

It’s about a system that still treats too many residents in the most expensive way possible — in crisis visits to the emergency room — rather than keeping people healthy in the community. It’s about having too few primary-care doctors addressing everyday needs to change that.

It’s about inadequate transportation to get to appointments and jail stays that cut patients off from family doctors. It’s about avoiding medical institutions often seen in the same light as the justice system that held Freddie Gray when he died: as biased, haughty and dangerous.

‘I Lost Two Aunts In That Hospital’

“When you walk into a hospital, it’s like walking into a courtroom,” said William Honablew Jr., who volunteers at LIGHT Health and Wellness, a nonprofit whose community services include helping those with HIV and other chronic illness navigate the system. “You know who’s in charge, and you know who’s not.”

Many in Sandtown have heard of Henrietta Lacks, an African-American woman whose tissue was used without permission by Johns Hopkins Hospital in the 1950s to establish a line of experimental cells. For years Baltimore blacks associated Hopkins, on the city’s east side, with the “night doctors” of African-American folklore who supposedly kidnapped black children for medical experiments, residents and community leaders say.

When you walk into a hospital, it’s like walking into a courtroom. You know who’s in charge, and you know who’s not.

Bon Secours Baltimore Health System, Catholic, nonprofit and the nearest inpatient provider to Sandtown, has reduced potentially deadly, in-hospital hazards such as pneumonia and blood and urinary tract infections in recent years. Adjusted for illness severity, its death rates for Medicare patients with major conditions such as heart failure and stroke are little different from national scores.

But to the frustration of hospital officials who say they deserve better, Bon Secours is still known across West Baltimore as “Bon Se-Killer.”

“I lost two aunts in that hospital, an uncle and two cousins. Five people,” said Arnold Watts, 60, in a grim accounting matched, unprompted, by several other residents interviewed.

The average Sandtown resident lives to be 69.7 years old, according to the Baltimore City Health Department — the same as life expectancy in impoverished North Korea.

Detailed data from the Maryland agency that regulates hospital prices, seldom seen by the public, illustrate why.

Residents of the ZIP code including Sandtown accounted for the city’s second-highest per-capita rate of diabetes-related hospital cases in 2011, the second-highest rate of psychiatric cases, the sixth-highest rate of heart and circulatory cases and the second-highest rate of injury and poisoning cases. Asthma, HIV infection and drug use are common.

Two out of ten babies born in Sandtown in 2013 were underweight — the highest percentage in any of Baltimore’s 55 neighborhoods. The share of Sandtown mothers getting early prenatal care fell by 25 percentage points in 2013 from the year before.

Dr. Jay Perman is a pediatric gastroenterologist who is president of the University of Maryland, Baltimore, which shares its downtown campus with the University of Maryland Medical Center. Perman, who says the school has a critical role to play in fighting poverty, looks out of his fourteenth-floor, paneled office across a boulevard that marks the beginning of Baltimore’s poor west side.

“Why,” he asks, “in the midst of this extraordinary health care enterprise that is present in Baltimore, with all this expertise, are we sitting here on this side of Martin Luther King (Blvd.) and on the west side of Martin Luther King (Blvd.) you have some of the most disappointing life expectancies that one could imagine?”

Two miles away, residents such as David Johnson start to provide an answer. Johnson, 52, sits in the nave of First Mount Calvary Baptist Church, waiting for food-bank vegetables and talking about being newly out of jail, lacking identification and trying to qualify for Medicaid.

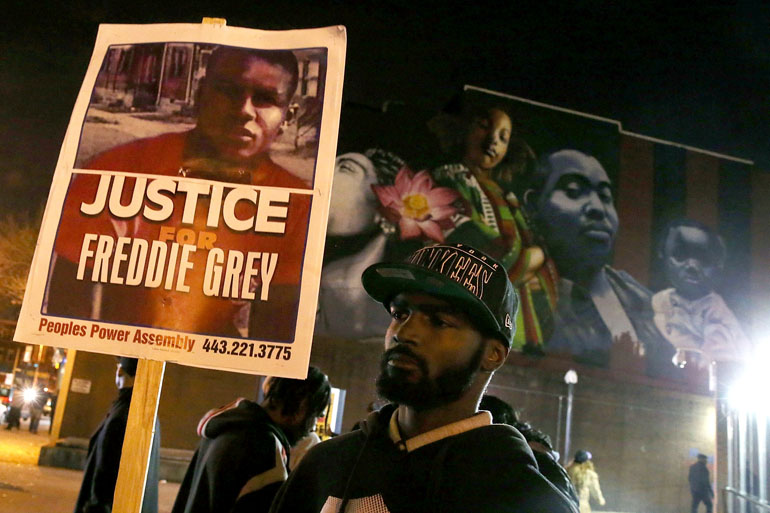

Police arrested Freddie Gray, 25, five blocks from the church last April, allegedly for carrying an illegal switchblade. He died of spinal injuries that prosecutors filing manslaughter charges blamed on police.

Western District police station, where officers removed Gray’s unconscious body from a prisoner van and protesters surged a week later, is a block south.

Months To Qualify For Medicaid

“I think I have diabetes,” said Johnson. “I know I have high blood pressure. I know that. I get dizzy a lot, especially when I wake up in the morning. I need to see a doctor.”

But he can’t. Baltimore jail authorities lost his identification cards, he said, before releasing him in October from an 11-month stay related to a drug arrest. He spent weeks reapplying for a Motor Vehicle Administration identification card, which social workers said he needed to qualify for Medicaid.

“You need ID to get ID, you know?” he joked. Nobody told him he could use incarceration credentials to qualify.

Medicaid’s expansion to include low-income adults was seen as an unprecedented opportunity to cover former inmates such as Johnson as they rejoin the community. (Inmates are not usually eligible while incarcerated.)

But limited administrative resources for release planning means sign-ups are often limited to the most severely ill, said Lena Hershkovitz, a vice president with HealthCare Access Maryland, a nonprofit working to increase enrollment.

“I know for a fact that he’s not unusual,” she said of Johnson. “I would say the majority of people leaving the prison or detention system are leaving without Medicaid.”

Last year the University of Maryland Medical Center found hepatitis C was causing potentially life-threatening damage to Antonio Davis’ liver, said Janet Gripshover, a nurse practitioner at the Baltimore hospital. Hepatitis C can also cause liver cancer.

Davis’ Medicaid plan, run by UnitedHealthcare, thrice denied doctors’ prescriptions for Harvoni, a new drug that can cure hepatitis C with no side effects but costs up to $90,000 for a full treatment, documents show. Davis, 58, was ineligible because he tested positive for illegal drugs or alcohol, United said in two letters to him.

“I’ve been off drugs and alcohol for six years,” he said, although he acknowledges drugs are probably how he got the virus long ago. “I don’t even drink near beer” — nonalcoholic beer.

Only by switching to a different Medicaid plan, run by Amerigroup, was he approved for Harvoni. Like many states, Maryland contracts with private insurers such as Amerigroup and United to provide Medicaid coverage.

Gripshover and other professionals acknowledge the drug’s high cost but say it saves lives and can save equally large expenses for treating cirrhosis and cancer. “There are no data” to support withholding Harvoni or other treatment from those who use illegal drugs, according to guidelines from associations of liver-disease professionals. United declined to comment on his case.

Communication barriers and “poor customer service” are also barriers to care in West Baltimore, according to a 2012 report by John Snow Inc., a Boston consultant hired by an association of community health centers.

William Ferebee, 66, has obstructive lung disease and a stent implanted after a 2001 heart attack. He avoids doctors at a University of Maryland Medical Center clinic because “they don’t even really come look at me,” he said. Instead, they give orders to a nurse or resident, “and then he comes in and says, ‘OK, here’s what we’re going to do.’”

William Ferebee, 66, has obstructive lung disease and a stent implanted after a 2001 heart attack. He avoids doctors at a University of Maryland Medical Center clinic because “they don’t even really come look at me,” he said. Instead, they give orders to a nurse or resident, “and then he comes in and says, ‘OK, here’s what we’re going to do.’”

A doctor at a nearby, independent clinic “is a sweetheart,” he said. “But it’s so hard to get an appointment.”

Distrust of the system often ensures there’s no communication at all.

Deborah Stevenson, 57, limps so badly with a damaged knee that sometimes people think she’s drunk. She believes she needs a knee replacement, “but I’m scared to get it,” she said. Her orthopedist “wouldn’t answer my questions and deal with me like a patient,” she said.

Even though she doesn’t have diabetes and her leg is otherwise healthy, her son speculated doctors might cut it off.

“I’m handicapped now,” she said. “I don’t want to be crippled.”

Fear of legal consequences also keeps people away from the health system. Some men worry doctors will report their undocumented address to social services, which they believe could reduce aid for female partners who live with them, said Wilson, the New Song pastor.

Medical privacy laws allow hospitals and clinics to help law enforcement officials trace suspects and fugitives. Residents subject to outstanding warrants fear they’ll be arrested if they seek care.

“Some people got a case out there — they’re not going to the health clinic,” Wilson said. “They’re going to die without giving up their information.”

Even when patients get access, care is disrupted by physician turnover, poor follow-up or insurance companies’ changing medical networks.

“The system is fragmented,” said Debbie Rock, who has run LIGHT Health and Wellness, on Sandtown’s western edge, since the 1990s. “I think that people need to go back and talk to each other. I think the doctors and the health insurance companies need to sit down and listen to each other.”

One homeless West Baltimore patient left an oral surgeon’s office with a wired jaw and no way to pay for the liquid nutrition he needed to feed himself, said Carol Marsiglia, senior vice president at the Coordinating Center, a nonprofit consulting organization that is working to reduce readmissions and emergency visits in the neighborhood.

A home-oxygen company wouldn’t serve a discharged lung patient because he had a $27 balance, she said. A hospital directed two home-health companies to teach a patient how to deal with a new colostomy bag; neither showed up. The Coordinating Center fixed the breakdowns.

Poverty makes Sandtown’s health worse. Many say poverty causes Sandtown’s poor health.

Four Liquor Stores And Three Sub Shops

Many residents hold jobs in government or manufacturing, run churches or collect pensions from the military or Social Security. Even so, the median Sandtown household income in 2011 was $22,000.

Roofs leak. Mold and mildew grow. Baltimore Gas and Electric cuts off energy to Sandtown households for nonpayment at twice the rate it does in the rest of the city. Lead paint violations like the kind that allegedly poisoned Freddie Gray are nearly four times higher in Sandtown than in Baltimore as a whole.

Drug and alcohol use are common. Diets are often poor. Many lack cars and the nearest supermarket is more than a mile away from the church.

“If we walk around this block, we’ll pass four liquor stores and three sub shops,” said Derrick DeWitt, pastor of First Mount Calvary, on Fulton Avenue.

Even small co-payments required by many health plans dissuade low-income West Baltimore residents from seeking care, the John Snow report found. Some constantly switch doctors to find the lowest price, leading to “disjointed services” and potential harm if information falls in the cracks, it found.

“I change doctors like I change underwear,” said Eddie Reaves, 64, who tries to find practices that won’t charge him copays as little as $12 or $15. His income is $1,170 a month, he said. In 2014, he added, “I must have seen a good total of about 10 doctors.”

Reaves has diabetes and high-blood pressure. He’s on Medicare because of a disability. He has applied twice to Medicaid since the health law expanded coverage two years ago. That would improve his benefits. But he never received the paperwork, he said.

The best care he ever received, Reaves said, was when he didn’t need any insurance card — when he was homeless.

Eddie Reaves, a diabetic with high blood pressure, said the best care he ever received was when he didn’t need any insurance card — when he was homeless. (Iman Smith/Capital News Service)

Health Care for the Homeless, a nonprofit a couple miles east of Sandtown, delivers comprehensive services to the homeless without regard for ability to pay.

“Didn’t have no bills,” Reaves said of the clinic when he used it a few years ago. “Your medicine they helped pay for. They did a lot for you. You could get your teeth done and everything. It was just great, man.”

The rest of the medical system is so unsatisfactory by comparison that low-income Baltimoreans sometimes claim to be homeless when they’re not, just to use the clinic, he said.

What happened after a 2004 car accident that broke Robert Peace’s pelvis is a glaring example of what many say is the kind of medicine that has been practiced too long in West Baltimore and what many say they are working to change.

Emergency surgery at UMMC fixed the fracture. But Peace developed a persistent bone infection. He received little or no follow-up care, he said, getting treatment only when the infection surged out of control and required repeated, expensive surgeries.

“The pain would be so intense — it’s like, wracking my body. I would literally sit there and shake,” he said. “That’s when I would know I had to go to the hospital, because I knew the infection was back.”

He said he required five more surgeries over a year and a half — the kind of return trips to the hospital, or “readmissions,” that the health industry and the Affordable Care Act of 2010 are trying to reduce by promoting coordination between hospitals and community doctors.

A 2004 car accident broke Robert Peace’s pelvis. He had emergency surgery at University of Maryland Medical Center but developed a persistent bone infection and received little or no follow-up care, he said. (Doug Kapustin for KHN)

“I’m blaming it on the follow-up,” said Peace, 58. “They knew the infection wasn’t going away, but the only time they would really tend to it was when I was in the hospital.”

Today Peace walks with a cane and a pronounced limp.

It’s a story that’s still too common in West Baltimore, said Antoine Bennett, a lifelong Sandtown resident and an elder at New Song Community Church.

“We’ve got a joke here, but it’s a serious joke,” he said. “If they ain’t medicating, they’re amputating or operating. But what’s missing is the care. Primary care.”

When asked about Peace’s case, UMMC spokesman Michael Schwartzberg said, “Much has changed in the Maryland hospital environment” since his surgeries. Improvements include new emphasis on preventing readmissions and “significant investment” in care coordinators and other post-discharge management, he said.

Keeping People Healthy And Out Of The Hospital

By many accounts, hospitals, doctors, health plans and governments in Annapolis, Maryland’s capital, and Washington are making unprecedented efforts to bridge the medical divide with Sandtown and the rest of low-income Baltimore.

The grand idea is to save money and simultaneously improve lives by keeping people healthier in the community instead of letting them become ill enough to land in the hospital.

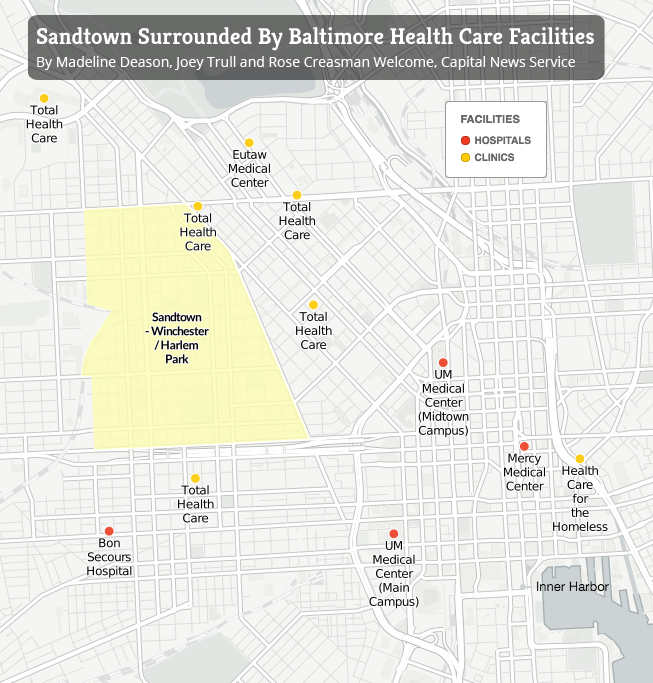

In October Bon Secours bought a nearby church that it intends to turn into a primary care and wellness center. UMMC and Bon Secours are working with “transition coaches” from the Coordinating Center to make sure people leaving the hospitals take medicine and schedule follow-up appointments. UMMC’s transition clinic serves hundreds of recently discharged patients.

Maryland is developing one of the most advanced electronic networks for letting medical providers collaborate by sharing patient records. Health Care for the Homeless has opened a clinic in Bon Secours.

Dr. Samuel Ross, Bon Secours’ CEO, talks about working more closely with the churches and continuing to improve the hospital’s outcomes and reputation.

Dr. Samuel Ross, CEO of Bon Secours Hospital (Doug Kapustin for KHN)

“No, it’s not solved,” he said. “We need to keep doing what we’re doing, and understand that some of this is a person at a time. There is no wholesale campaign or branding message that’s going to cause people to say, ‘You’re wonderful.’”

In 2012 Maryland’s legislature created “health enterprise zones” to increase the supply of primary caregivers in West Baltimore and other underserved areas. UMMC puts emergency room patients in touch with a primary care doctor if they don’t have one.

In September hospitals proposed taxing insurance companies, employers and other payers so they could hire up to 1,000 caregivers directly from West Baltimore and other low-income communities with poor health results.

The Baltimore health department is pressing hospitals to collaborate on high-risk patients and is building ties with lower-income neighborhoods by hiring residents, said Dr. Leana Wen, the city’s health commissioner.

Baltimore’s B’more for Healthy Babies program has reduced the city’s African-American infant mortality rate by nearly a third since 2009, to 12.8 per thousand births. But that’s still a fifth higher than the African-American rate for all of Maryland.

University of Maryland Medical Center has workshops and internships for high schoolers interested in health careers. The University of Maryland, Baltimore, got a federal grant to mentor and train West Baltimore middle schoolers to increase the number of African-Americans in health care jobs.

More and more professionals echo UMB’s Perman, who said a medical professional’s duty to patients does not end at the hospital or clinic door.

“As a profession, as an industry, we have not sufficiently appreciated, let alone done something about, the impact of social determinants” such as poverty, poor housing, lack of food choices and low education, he said. “Guys like me and gals like me can easily say, ‘I made the correct diagnosis. I wrote a proper prescription. I’m done.’ What I say to my students is, if you think you’re done — if ‘done’ means the patient is going to get better — you’re fooling yourself.”

Maryland’s ambitious overhaul of hospital reimbursement, authorized by the health law, is supposed to back that philosophy with powerful incentives. Starting in 2014, hospitals have been assigned annual budgets for all government and private payers, instead of being paid per admission or treatment.

The idea is to boost their motivation to contain costs by delivering preventive, community care — to pay them for keeping people out of the hospital. Hospitals are also getting penalized for excessive readmissions and preventable harm such as infections and accidental punctures.

“It’s a daunting task… when we talk about joblessness and poor nutrition and violence in the neighborhoods,” said Dr. Walter Ettinger, chief medical officer of the University of Maryland Medical System. “But we all feel driven by our mission to serve our communities in a better way, and now the finances are aligned to do that.”

Poor people, however, know that between ambitions and accomplishments is a chasm of disappointment.

In the face of wider primary-care shortages and the difficulty for doctors to make a living in low-income neighborhoods, the zone fell far short of its original goal of adding 48 primary care professionals to West Baltimore.

“Some of the goals and objectives across almost all of the zones were a bit ambitious,” said Maura Dwyer, a senior policy advisor for the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

In 2014 People’s Community Health Center closed three nonprofit clinics for low-income patients in Baltimore and later entered bankruptcy proceedings, demonstrating the difficulty.

Total Health Care operates several federally qualified health centers in Baltimore. (Iman Smith/Capital News Service)

Officials at Total Health Care, a federally supported nonprofit with several primary-care clinics near Sandtown, say they are proud of their service to West Baltimore.

“We want to bring the standard health in this neighborhood up to national standards,” Dr. Marcia Cort, Total’s chief medical officer, told students from the Merrill College. “We don’t want it to be the neighborhood and area [where] life expectancy is low and people are dying from preventable things.”

Still, she said, “Baltimore City is in a health crisis.”

Readmission rates for Bon Secours were still the highest in the state in 2014, although the Coordinating Center’s transition coaches helped reduce them by 14 percent from the year before.

Readmissions for UMMC’s midtown campus were second highest statewide after declining 5 percent, also with work by transition coaches. At UMMC’s downtown campus, readmissions were fifth highest in the state and declined 2 percent.

But state financing to pay for the transition coaches expires at the end of March. The Coordinating Center is optimistic it will be renewed but nothing is set, Marsiglia said.

In 2014 only 37 percent of surveyed Bon Secours patients “strongly agreed” that they understood their care after they left the hospital. For UMMC patients the figure was 51 percent.

Many resent that it took this long for the industry to try the very solutions — improving primary care, giving communities resources to help themselves — that residents of neighborhoods like Sandtown have been advocating for years.

“Unfortunately the hospitals didn’t hear us,” said Diane Bell-McKoy, CEO of Associated Black Charities, a Maryland nonprofit. “As a person of color giving that information — most people think we don’t know what we’re talking about.”

Distrust of the system, still more widespread than medical officials imagine, is passing to a new generation, residents say.

“It’s a culture that has come about over time, because younger people have seen or feel like their parents and their grandparents didn’t get the best medical treatment when they went to the hospital,” said First Mount Calvary’s DeWitt. “So they have this why-go attitude.”

Derrick DeWitt, pastor of First Mount Calvary on Fulton Avenue in Sandtown, said the “why-go attitude” toward medical treatment is being passed down to a new generation. (Nora Tarabishi/Capital News Service)

On Dec. 9, Maryland regulators shrank funding by two-thirds for the proposal made three months earlier to create hospital jobs in poorer neighborhoods.

Other initiatives do little to address the low incomes and unemployment linked to Sandtown’s poor health. Nor do they simplify the shifting maze of private and government insurance plans and hospital and doctor networks that patients must navigate to get care.

One example: Nearly 2,000 low-income Medicaid members, including many in Sandtown and nearby, had to change coverage in August or get new doctors because United dropped University of Maryland Faculty Physicians from its Medicaid network in a contract dispute, said Shannon McMahon, deputy secretary of the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

United “had thorough continuity of care measures in place before the contract ended to ensure ongoing care was not disrupted,” said company spokesman Ben Goldstein.

For many residents, enrolling in a plan is too complicated and time-consuming, requiring time off from work to get coverage they don’t understand and can’t afford, said LIGHT Health’s Rock. In some ways the health law and its new coverage rules have made things more complex, she said.

“As the landscape is changing, people really just don’t know what to do,” she said. “They sit you down with somebody that’s supposed to help you fill [an insurance application] out, which is like a Charlie Brown episode. Once you start on the second page it’s like ‘Wah, wah, wah.’ You don’t hear nothing else. You walk out and it’s like, ‘What happened?’”

David Johnson, who was concerned about his blood pressure, dizziness and possible diabetes, joined Medicaid in December. It took two months, three trips to the motor vehicle bureau to get a new ID and two trips to social services to enroll.

An estimated 133,000 eligible but uninsured Marylanders still hadn’t signed up for Medicaid as of October. As of early February, Eddie Reaves, the diabetic who gave up applying after his second attempt, was still among them.

This story is part of a reporting partnership between Kaiser Health News and University of Maryland College Park’s Philip Merrill College of Journalism, which operates Capital News Service. KHN and students from the school are examining how Baltimore’s nationally respected health system serves the community where violence flared in April after Freddie Gray was fatally injured in police custody. The project is continuing. To see all the students’ work go to the CNS website.