Even as Massachusetts celebrates a dip in the growth rate of health care costs, state lawmakers are still working feverishly on cost-control bills.

The critical question: How much health care spending should the state aim to cut? Two unlikely bedfellows, the state’s largest employer group and a coalition of congregations, are putting the pressure on legislators to go deep.

In separate actions Tuesday night, The Greater Boston Interfaith Organization and the state’s largest employer group, Associated Industries of Massachusetts posted the same goal. Health care spending has been growing at least twice as fast as the rest of the state’s economy. But these groups say the state must hold all health care spending – including both government spending and private spending — to a rate of two percentage points below the state’s gross state product, or GSP.

GSP -2 would be a dramatic change – that’s like your boss putting a pay freeze on top of two salary cuts. For almost two decades, health care costs in Massachusetts have outpaced the commonwealth’s gross state product.

“Our state must take strong action to reverse the trend of the growth of health care costs and provide incentives to create a health care system that rewards quality not quantity; health care not sick care,” GBIO president, Rev. Burns Stanfield, said at a church rally of 325 members.

The same evening, in a blog post AIM president Rick Lord said, “The math is pretty simple.” If one third of all health care spending is waste, or care that doesn’t make people better, then “the process of keeping health care cost growth below economic growth seems reasonable,” Lord argued.

The Massachusetts Hospital Association says GSP -2 is “a really bad idea” that would force massive layoffs and the closure of some hospitals. The association’s president and CEO, Lynn Nicholas, believes people have the wrong idea about how waste occurs in health care.

“Business people think of waste as something like closing off parts of an assembly line,” says Nicholas. “The waste in health care is marbled in like fat in a steak and it has to be teased out very carefully so that you don’t destroy what’s left.”

A coalition that includes at least two dozen hospitals, physician groups, health plans and employers has another idea: hold the costs to gross state product plus one.

Stuart Altman, who chairs the Eastern Massachusetts Healthcare Initiative, says just getting health care in line with the gross state product would be a major achievement. Altman, a health care economist who advised Presidents Nixon, Clinton and Obama, said he is “concerned about both what it (GSP -2) would do to the delivery system, and to the quality of care, to patients, and what it would do to the economy of Massachusetts. It’s just too drastic a cut.”

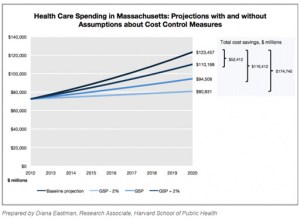

The difference between GSP+1 and GSP-2 is roughly $7 billion in 2015, when total health care spending in Massachusetts would hit roughly $89 billion. By 2020, the difference would grow to about $21 billion.

So how might the different spending goals affect patients? It depends, of course, on whom you ask. Don Berwick, the former president and CEO at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, says the state can cut costs while protecting patients.

“I do not believe that is it necessary or wise to reduce costs by hurting patients,” continues Berwick. “This is done simply by routing out waste in practice that pervades a lot of the American health care system.”

It’s the prospect of job losses and patients rebelling against changes in their care that is scaring some state legislators. House Speaker Robert DeLeo said last week that he would propose health care spending “more in line with state economic growth” which is currently 3.7 percent. Legislation from the Massachusetts House and Senate expected out next month or in May.

Paul Ginsburg, of the Center for Studying Health System Change, says the goal Massachusetts sets for controlling health care costs will get a lot of national attention. But he says the target is not as important as “what they (regulators) do if the goal isn’t met. That will be the most instructive thing” for the country.

Governor Deval Patrick has suggested that state regulators review and reject contracts between insurers and providers that exceed whatever target the state sets. There’s no word yet from the House and Senate on proposed consequences.