When Massachusetts passed its landmark health coverage law under Gov. Mitt Romney in 2006, no one claimed the state would get to zero, as in 0 percent of residents who are uninsured. But numbers out this week suggest Massachusetts is very close.

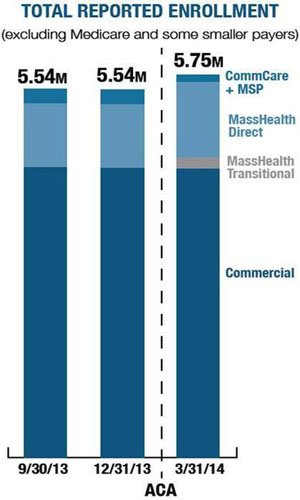

Between December 2013 and March of this year, when the federal government was urging people to enroll, the number of Massachusetts residents signed up for health coverage increased by more than 215,000. If that number holds, the percentage of Massachusetts residents who do not have coverage has dropped to less than 1 percent.

“We’re thrilled that we are getting this close to universal health care access,” said the Rev. Burns Stanfield, president of the Greater Boston Interfaith Organization.

Stanfield says a report out last month that found mortality rates dropped in the first four years of expanded coverage, coupled with the insurance numbers, show that “our statewide move to universal access is working, and it’s a powerful witness to the nation.”

But that kind of enthusiasm is not coming from the state – yet.

“These numbers are a sign that we are moving in the right direction, but there is still a lot of uncertainty about what they will ultimately mean to the total level of health insurance coverage in Massachusetts,” says Áron Boros of the Center for Health Information and Analysis, the state agency that tallied the latest insurance figures.

Uncertainty might be an understatement. There is still a tremendous backlog of applications to process. Most of the new enrollees are in a temporary coverage plan because the state, with its failed website, has not been able to figure out if these people qualify for free or subsidized care.

What if they don’t qualify for help, asked Lora Pellegrini, president of the Massachusetts Association of Health Plans, will these new enrollees be willing to pay a premium?

“The real challenge is going to be to move these folks from the temporary coverage into the permanent coverage where they belong, and then see if we’re able to retain these numbers,” Pellegrini said.

There are reasons to think the numbers may hold. Despite the broken website and confusion about deadlines and eligibility, it looks like more than 200,000 residents who did not have health insurance last year pushed to enroll.

There are some explanations for why:

First, the big federal enrollment campaign that ran from Oct. 2013 until March might have caught people’s attention.

Second, more residents are eligible for free or subsidized help coverage under the new federal insurance law.

Third, most of the remaining uninsured in Massachusetts were low-income workers who could not afford premiums under their employers’ plans. Under the previous Massachusetts health care law, enacted under then-Governor Mitt Romney, workers were not allowed to sign up for state-subsidized insurance if they had access to insurance through work. The federal law lifts that restriction in part.

“It is hard not to look at this and say, if it turns out the numbers are actually correct — that’s a big if — this is good,” said Gail Wilensky, a senior fellow at Project Hope and former health care adviser to President George H. W. Bush. “It is urgent that we have confirmation that continued enrollment after the first year can happen and, in fact, in a place like Massachusetts, did happen.”

The state may be dropping even closer to zero percent uninsured than the numbers from CHIA indicate because of movement in the coverage market. The CHIA analysis reflects March numbers when 167,000 residents were in temporary coverage but as of this week, Governor Deval Patrick’s office says there are 217,000 people in that plan. It’s not clear how many of these people are newly insured. Private health insurers lost at least 10,000 members during the first quarter of this year.

Massachusetts will continue to have undocumented residents and others who are uninsured. Making sure coverage is affordable is an ongoing challenge and paying to subsidize insurance for more residents may strain the state budget. But Massachusetts may have become the first the state in the country where nearly everyone can focus more on their health and less on whether they can see a doctor if they are injured or ill.

This story is part of a reporting partnership with NPR, WBUR and Kaiser Health News.