On orders from Congress, Medicare is easing up on its annual readmission penalties on hundreds of hospitals serving the most low-income residents, records released last week show.

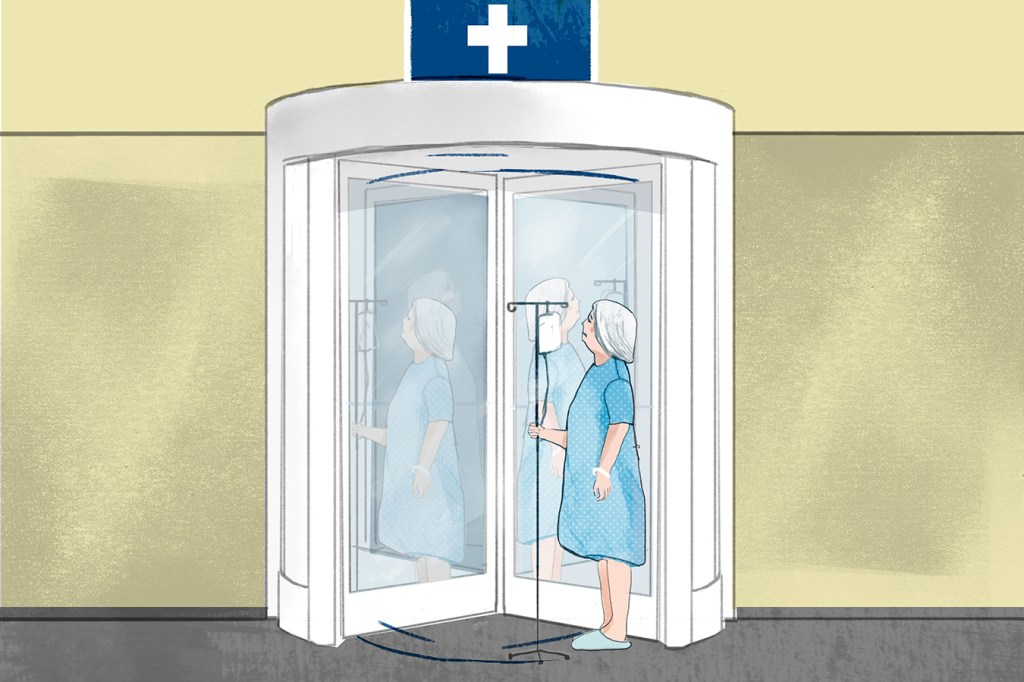

Since 2012, Medicare has punished hospitals for having too many patients end up back in their care within a month. The government estimates the hospital industry will lose $566 million in the latest round of penalties that will stretch over the next 12 months. The penalties are a signature part of the Affordable Care Act’s effort to encourage better care.

But starting next month, lawmakers mandated that Medicare take into account a long-standing complaint from safety-net hospitals. They have argued that their patients are more likely to suffer complications after leaving the hospital through no fault of the institutions, but rather because they cannot afford medications or don’t have regular doctors to monitor their recoveries. The Medicare sanctions have been especially painful for this class of hospitals, which often struggle to stay afloat because so many of their patients carry low-paying insurance or none at all.

In a major change to its evaluation, the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) this year ceased judging each hospital against all others. Instead, it assigned hospitals to five peer groups of facilities with similar proportions of low-income patients. Medicare then compared each hospital’s readmission rates from July 2014 through June 2017 against the readmission rates of its peer group during those three years to determine if they warranted a penalty and, if so, how much it should be.

The broader issue is whether medical providers that serve the poor can be fairly judged against those that care for the affluent. This has been a continuing topic of contention as the government seeks to accurately measure health care quality. It is particularly a concern in efforts to consider patient outcomes in setting pay rates for doctors, nursing homes, hospitals and other providers.

Overall, Medicare will dock payments to 2,599 hospitals — more than half in the nation— throughout fiscal year 2019, which begins Oct. 1, a Kaiser Health News analysis of the records found. The harshest penalty is 3 percent lower reimbursements for every Medicare patient discharged in fiscal year 2019. The number of hospitals and the average penalty — 0.7 percent of each payment — are almost the same as last year.

But the new method shifted the burden of those punishments. Penalties against safety-net hospitals will drop by a fourth on average from last year, the analysis found.

“It’s pretty clear they were really penalizing those institutions more than they needed to,” said Dr. Atul Grover, executive vice president of the Association of American Medical Colleges. “It’s definitely a step in the right direction.”

(Story continues below. Trouble viewing this table? Download the data here.)

Safety-net hospitals that will see their penalties cut by half or more include many urban institutions, such as Sutter Health’s Alta Bates Summit Medical Center in Oakland, Calif.; Providence Hospital in Washington, D.C.; and Hurley Medical Center in Flint, Mich. Sixty-five safety-net hospitals — including Franklin Medical Center in Winnsboro, La., Astria Toppenish Hospital in Toppenish, Wash., and Emanuel Medical Center in Swainsboro, Ga. — that had been penalized last year escaped punishment entirely this year.

Conversely, the average penalty for the hospitals with the fewest low-income patients will rise from last year, the analysis found.

Before the program began, roughly 1 in 5 Medicare beneficiaries were readmitted within a month. Hospitals were paid the same amount regardless of how their patients fared after being discharged. In fact, a readmission was financially advantageous as hospitals would be paid for the second hospital stay, even if it might have been avoidable.

Since the sanctions began, Medicare has evaluated each year rates for readmitted patients who had originally been treated for heart failure, heart attacks and pneumonia. And it has reduced its payments to more than half of hospitals based on those rates. The evaluations have since expanded to cover chronic lung disease, hip and knee replacements and coronary artery bypass graft surgeries.

Medicare counts patients who returned to a hospital within 30 days, even if it is a different hospital than the one that originally treated them. The penalty is applied to the first hospital.

Medicare exempts hospitals with too few cases, those serving veterans, children and psychiatric patients, and critical-access hospitals, which are the only hospitals within reach of some patients. In addition, Maryland hospitals are excluded because Congress lets that state set its own rules on how it distributes Medicare money.

(Story continues below.)

In its revised method this year, Medicare distinguished hospitals that serve a high proportion of low-income patients by looking at how many of the hospital’s Medicare patients were also eligible for Medicaid, the state-federal program for the poor. American Hospital Association officials say that while they considered this an improvement, it isn’t a perfect reflection of poor patients. For one thing, they say, hospitals in states with more restrictive Medicaid coverage do not appear through this formula to have as challenging patient populations as do hospitals in states with higher Medicaid eligibility.

Akin Demehin, the association’s director of quality policy, said CMS might consider linking its records to Census records that show income and education level of patients.

“It might give you a more precise adjuster,” he said.

The hospital industry remains critical of the overall program, saying that stripping hospitals of revenue because of poor performance only makes it harder for them to care for patients.

Congress’ Medicare Payment Advisory Commission in June concluded that the penalties from previous years successfully pressured hospitals to reduce the numbers of returning patients — and helped save Medicare about $2 billion a year.

In its analysis of the approach’s effectiveness, Congress’ advisory commission rejected some of the hospital industries’ complaints about Medicare’s Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program: that hospitals may have tried to get around the penalties by keeping patients under “observation status” and that discouraging rehospitalizations may have led to extra deaths.

The commission found that between 2010 and 2016 readmission rates fell by 3.6 percentage points for heart attacks, 3 percentage points for heart failure and 2.3 percentage points for pneumonia. At the same time, readmissions caused by conditions that do not factor into the penalties fell on average 1.4 percentage points, indicating hospitals were focusing on lowering unnecessary readmissions that could hurt them financially.

The commission wrote: “We conclude that the [penalties] contributed to a significant decline in readmission rates without causing a material increase in ED [emergency department] visits, a material increase in observation stays, or a net adverse effect on mortality rates.”

This fall, Medicare will attack the readmissions from another angle by issuing penalties on skilled nursing facilities that send recently discharged residents back to the hospital too frequently.

KFF Health News’ coverage related to aging and improving care of older adults is supported in part by The John A. Hartford Foundation.