The day he learned he had liver cancer, Michael J. Reece, 56, was spending nights in a Seattle homeless shelter, leaving each morning to wander the city streets.

For weeks, he’d been in constant pain, worried about the swelling in his legs and gut. Then he faced surgery and chemotherapy — and the dread that comes with a potentially deadly diagnosis.

“I cried,” recalled Reece, a former drug addict who was estranged from his family and cut off from traditional medical care.

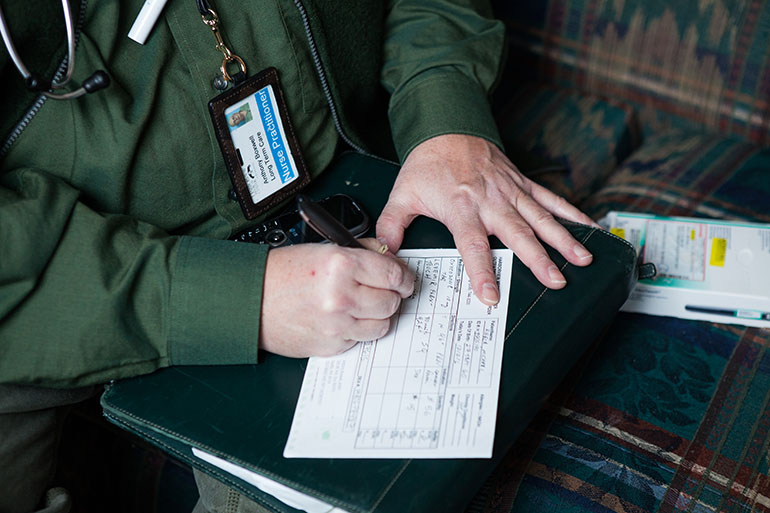

That’s when he met Tony Boxwell, a bald, burly nurse practitioner at the heart of what experts say is the first U.S. program that sends mobile teams to provide palliative care — comfort care — to homeless people facing terminal illness.

“A nurse at the shelter referred him to us,” said Boxwell, 58, who visits Reece every two weeks. “We hooked up oncology and took it from there.”

Since January 2014, the pilot project run by Seattle/King County Health Care for Homeless Network and UW Medicine’s Harboview Medical Center has served more than 100 seriously ill men and women in the Seattle area, tracking them down at shelters and drop-in clinics, in tents under bridges and parked cars.

“It’s really necessary that people be taken care of where they are,” said Dr. Daniel Lam, director of inpatient and outpatient palliative care services.

The team connects clients with medical care, paid for through Medicaid or hospital charity, and then makes sure they follow up. They help patients evaluate complicated treatment options, and, when the time comes, they may be with them when they die.

The effort, funded through 2017 by a federal grant of $170,000 a year, aims to reduce unnecessary or unwanted end-of-life care and to give homeless people a say in the process.

Too often, Lam said, such patients are treated in emergency rooms during crises and wind up receiving feeding tubes, mechanical ventilation and long intensive care stays.

“These therapies have their place,” Lam said. “But we noticed people were getting care they might not have wanted.”

So far, for patients enrolled in the program for six months, the Seattle project has reduced hospital stays by 25 percent and emergency room visits by half, according to a June report.

“There are times when our medical system focuses on longevity,” Lam said. “We’re focusing on comfort and independence.”

It’s part of a larger move to address the booming numbers of elderly homeless, expected to reach 95,000 in the U.S. by 2050, according to the National Health Care for the Homeless Council (NHCHC).

“We’re seeing a huge demographic shift,” said Dr. Margot Kushel, a professor at the University of California San Francisco who studies health care use in homeless adults and other vulnerable people. “It’s people who are newly homeless in their 50s and 60s.”

Between 2008 and 2014, U.S. programs offering health care to the homeless saw a 50 percent jump in the number of patients older than 50. Living on the streets cuts life expectancy by about 12 years, NHCHC research shows.

“How do you manage cancer when you’re sleeping in your car? How do you manage end-stage cardiovascular disease when you’re sleeping on a bench?” Kushel said. “They’re having these long, slow, horrible deaths.”

Worldwide, there are only a few other mobile palliative care programs, all outside the U.S. The closest one in North America is the Palliative Education and Care for the Homeless program — known as PEACH — in Toronto.

Other U.S. programs, such as medical respite and hospice, offer care for terminally ill homeless people, but they’re often limited by space and strict rules, said Sabrina Edgington, NHCHC director of special projects.

“There are going to be times when you’re not going to be able to place individuals in a fixed site, like hospice,” she said. “They might want to be surrounded by their own community, they may have caregivers.”

A mobile program may be more likely to engage the hardest-to-reach patients, those distrustful of medical care and outsiders, Edgington added.

Tony Boxwell and his partner, Joe Hufford, a registered nurse, agreed. They travel around Seattle by bus, not by car, partly in hopes of connecting with sick homeless clients. For months, they regularly visited a dying client at a notorious Seattle homeless camp known as “The Jungle.”

“She couldn’t leave her stuff to go to the pharmacy,” Boxwell said. “It would be stolen.”

The medical services may be simple. On a recent visit with Reece, Hufford took his blood pressure — it read 130/75 — while Boxwell arranged medication refills. A social worker, Michael Light, discussed Reece’s plans to return to college soon.

More important, though, is the coordination provided by the team. During Reece’s visit, Boxwell took a call from a surgeon who wanted to make sure a different client was taking postoperative medications. Hufford said he recently helped a terminally ill client locate her mother’s grave to help put her at peace.

“What this team is doing is becoming part of the patient’s family,” Lam said. “Often, they have so much shame: ‘Do I even deserve care?'”

Many of the patients who joined the program in 2014 have died, usually within weeks or months of receiving palliative care. But some, like Reece, are recovering. Surgery to remove a liver tumor was successful, and with Boxwell’s help, he received drugs that appear to have cured his hepatitis C.

Reece qualified for a small studio apartment in a low-income housing complex and said he’s making plans to go back to college now that his illness is in remission.

“Getting cancer was really good for him, which is ironic,” Boxwell said. “This isn’t brain surgery or rocket science. It’s pretty basic. It’s just showing up and saying ‘How can I help you?'”

KHN’s coverage of end-of-life and serious illness issues is supported by The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.