Two years ago General Dynamics, one of the biggest federal contractors, reported a quarterly loss of $2 billion. An “eye-watering” result, one analyst called it.

Diminishing wars and plunging defense spending had slashed the weapons maker’s revenue and left some subsidiaries worth far less than it had paid for them. But the company was already pushing in a new direction.

Soon after Congress passed the landmark Affordable Care Act, the maker of submarines and tanks decided to expand its business related to health care. Its 2011 purchase of health-data firm Vangent instantly made it the largest contractor to Medicare and Medicaid, huge government health plans for seniors and the poor.

“They saw that their legacy defense market was going to be taking a hit,” said Sebastian Lagana, an analyst with Technology Business Research, a market research firm. “And they knew [the ACA] was going to inject funds into the health care market.”

They were right. In a way that is deeply changing Washington contracting, growth opportunities from the federal government have increasingly come not from war but from healing, an examination by Kaiser Health News and The Washington Post shows.

Politics are frozen. Budgets are tight. But business purchases by the Department of Health and Human Services have doubled to $21 billion annually in the last decade and are expected to continue rising.

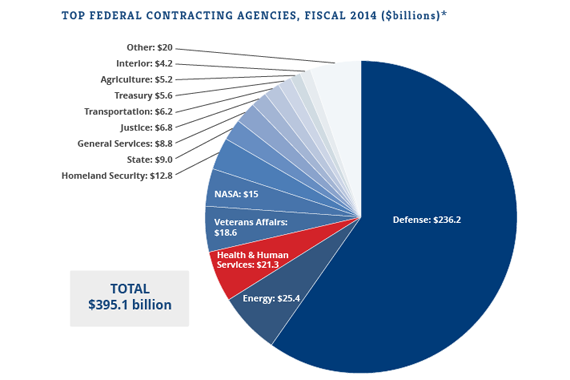

HHS is now the No. 3 contracting agency, thanks to health-law spending combined with outlays for computer upgrades and Medicare’s drug program that grew during the administration of George W. Bush. HHS outranks NASA and the Department of Homeland Security in business deals and spends more than the departments of Justice, Transportation, Treasury and Agriculture combined, federal data show.

If health care is “the new oil,” as some investors hope, HHS is one of the richest fields — along with massive opportunities in health-related computer spending by the departments of Defense, Veterans Affairs and Treasury.

“The DOD market is very weak,” said Steve Kelman, a Harvard management professor and contracting specialist. “The two growth markets are cybersecurity and health care. So everybody’s trying to get into those.”

The new money is buying medical-record software, insurance websites, claims processing, data analysis, computer system overhauls, consumer education and consulting expertise to control costs and identify fraud.

True, it’s a fraction of the $200 billion-plus the Pentagon spent on planes, bombs and other purchases in fiscal 2014. But thanks largely to automatic cuts set in 2011, defense contracting has dipped by more than a third since 2008 despite continuing conflict in Afghanistan and the Middle East.

Few expect that to happen to health contracting — even with limited budgets and Republicans opposed to the health law controlling both sides of Congress. Analysts expect the Ebola crisis to add billions more to an HHS budget that was already expected to grow.

“It’s going to be really hard to find more money,” said Stephen Fuller, an economist at George Mason University who follows federal spending closely. “But I would think HHS is in a position to sustain their funding levels and gain some as well where other agencies are going to find it more difficult just to keep what they have.”

HHS’ contracting budget is separate from the billions the agency pays in reimbursement to caregivers of Medicare patients; its grants to states for Medicaid; and its awards through the National Institutes of Health to clinical research institutions such as the Johns Hopkins University.

Traditionally HHS vendors processed Medicare claims, made vaccines and managed information technology. HHS spending had already spiked in 2009, before the health law was passed, thanks to extraordinary purchases of H1N1 flu vaccines. But the ambitious ACA, intended to expand health coverage, overhaul payments and reengineer care —and with ample budgets to attempt all three — changed the game.

“Just because of the Affordable Care Act our health care business has probably doubled in the last five years,” said Nelson Ford, CEO of LMI Government Consulting, which helps HHS analyze and regulate the new, private insurance plans sold under the law.

The law effectively created major companies from scratch as well as growing new divisions at established businesses.

“It just occurred to me: If this bill does become law it will be a level playing field [for contractors] and we’ll have a head start,” said Sanjay Singh, who founded Reston-based hCentive based on the Affordable Care Act’s promise. “And we can build a company.”

Today hCentive employs more than 650 people. The company built the federal government’s online marketplace for small-business health plans and is working on insurance portals for Massachusetts, New York, Colorado and Kentucky.

Business at HighPoint Global, with offices in Virginia, Maryland and Indiana, ballooned from a few million to more than $100 million annually after it landed the job of training and quality control for dozens of call centers handling questions about the insurance marketplaces, federal data show. HighPoint CEO Ben Lanius declined a request for an interview.

For contractors, profiting from the health law goes far beyond the $840 million-plus HHS has already spent on the troubled healthcare.gov portal. (This year the agency fired CGI Federal, the site’s primary contractor, and replaced it with Accenture. HHS contracted with CGI for work worth $339 million the last two years; with Accenture, $192 million in contracts, records show.)

Defense giant Serco has done more than $400 million worth of business with HHS in the past two years, records show, much of it for collecting paper insurance applications that surged when the online marketplaces failed.

HHS’ innovation lab, with a $10 billion budget over a decade, is hiring research firms such as Mathematica to test alternatives to traditional, “fee for service” medicine that encourages unnecessary procedures. The ACA also furnished an extra $350 million to hire cyber sleuths to fight Medicare fraud.

A related law, the HITECH Act of 2009, steered another $30 billion via Medicare reimbursements to spur hospitals and doctors to buy medical-record software from private industry.

For traditional defense contractors, health care isn’t the new oil. It’s the new F-35 fighter or Zumwalt-class destroyer.

“This is a pretty exciting time to be in the federal health IT space,” said Horace Blackman, Lockheed Martin’s vice president of health and life sciences. “The biggest opportunities I would point to are efforts associated with the Affordable Care Act.”

While Lockheed has run HHS computers for a long time, its business with the agency has increased by more than half since 2006 to $300 million annually, according to federal records.

The company won part of a $15 billion data management contract from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services in 2012, along with Accenture, CGI Federal and others. It’s bidding with many others on another giant health job — an $11 billion Pentagon contract to modernize the military’s computer medical records.

Defense vendors are recycling products from battlefield to bedside. Lockheed says it converted missile-defense software into a hospital tool for the early identification of sepsis, a life-threatening response by the body to infection.

“We’re seeing a lot of these companies quietly repositioning and reusing their legacy capabilities,” said John Caucis, a senior analyst with Technology Business Research.

Along with cybersecurity smarts, Washington employers especially prize health analytics skills, recruiters say.

“We have 200 epidemiologists. We have clinical statisticians. We have physicians. We have nurses,” said Amy Caro, head of the health division at Northrop Grumman, better known for its B-2 stealth bomber.

Among other HHS work, Northrop manages data sharing for the National Institutes of Health; helped launch the health law’s accountable care organizations to control costs and improve care; and turned telecommunications software into a Medicare fraud detector.

The quickest way to acquire a particular expertise needed by HHS, some contractors have found, is often to mimic General Dynamics and buy somebody already doing the work.

In October Xerox said it acquired Consilience Software, maker of patient case-management and disease-surveillance programs for government agencies. The same month defense and intelligence giant Booz Allen Hamilton said it bought the health division of Genova Technologies, a tech company that has done $90 million in HHS business since the health law was passed, according to federal records.

The deal is part of a larger push by Booz, majority owned by the Carlyle Group, a private equity firm, to sell technology services and consulting to HHS.

Its yearly business with the agency has quadrupled in the last decade to $170 million even as its overall revenue from the federal government has shrunk, according to contracting data. (However, the extent of Booz’s government work is unclear because its jobs for spy agencies don’t show up in official records, contracting specialists say.)

This summer Booz won part of a huge (potentially $7 billion) job to help HHS’ innovation lab design, run and evaluate tests to improve care results and control costs. Other awardees include RTI International, a nonprofit; Deloitte, a consulting firm; the Lewin Group, a consultancy owned by insurer UnitedHealth Group; and Truven Health Analytics, a research shop owned by private equity investors Veritas Capital.

Booz officials did not respond to repeated requests for interviews.

Health-care acquisitions by defense contractors don’t always work smoothly. In 2011 General Dynamics paid Veritas nearly $1 billion for Vangent, a seller of health information technology and business services.

General Dynamics did not make executives available for interviews. But the deal did not go as well as the company hoped, as Vangent’s corporate culture clashed with that of the buyer, said Technology Business Research’s Lagana. Part of General Dynamics’ $2 billion quarterly loss at the end of 2012 was — ironically — related not to defense but to Vangent and its health-care work, he said.

But thanks to Vangent, the company got the task of staffing call centers to explain healthcare.gov to consumers. That job became bigger than anybody imagined when the site crashed during insurance enrollment a year ago. General Dynamics ended up hiring 8,000, mostly temporary workers to run hotlines for Obamacare as well as Medicare.

This year healthcare.gov is working better, by many accounts. Enrollment began Nov. 15. Again General Dynamics has been hiring to answer the phones. The company’s $815 million in spending commitments from HHS made it the agency’s top contractor for fiscal 2014, not counting vaccine makers.

And because its call-center jobs are “cost-plus” contracts, every hire comes with a built-in profit.