When Bruce Hodgins went to the doctor for a checkup in Sioux City, Iowa, he was asked to complete a lengthy survey to gauge his health risks. In return for filling it out, he saved a $10 monthly premium for his Medicaid coverage.

In Las Cruces, N.M., Isabel Juarez had her eyes tested, her teeth cleaned and recorded how many steps she walked with a pedometer. In exchange, she received a $100 gift card from Medicaid to help her buy health care products including mouthwash, vitamins, soap and toothpaste.

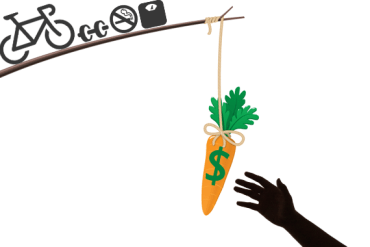

Taking a cue from workplace wellness programs, Iowa and New Mexico are among more than a dozen states offering incentives to Medicaid beneficiaries to get them to make healthier decisions — and potentially save money for the state-federal health insurance program for the poor. The stakes are huge because Medicaid enrollees are more likely to engage in unhealthy practices, such as smoking, and are less likely to get preventive care, studies show.

Taking a cue from workplace wellness programs, Iowa and New Mexico are among more than a dozen states offering incentives to Medicaid beneficiaries to get them to make healthier decisions — and potentially save money for the state-federal health insurance program for the poor. The stakes are huge because Medicaid enrollees are more likely to engage in unhealthy practices, such as smoking, and are less likely to get preventive care, studies show.

For years, private employers and insurers have used incentives to spur employees and members to quit smoking, lose weight and get prenatal care, although the record of those programs for changing long-term behavior is mixed, studies show. “Financial incentives are effective at improving healthy behaviors, though the effect of incentives may decrease over time,” said a report last year by the Center for Health Care Strategies, a research group based in Hamilton, N.J.

Another analysis published this month in the journal Preventive Medicine, which looked at 34 studies, found that workplace and other incentives can change health behaviors in the short term, but the effects dissipated once the incentives were taken away.

The Affordable Care Act is behind the latest push of wellness incentives in Medicaid. Besides Iowa and New Mexico, several other states that have expanded Medicaid under the health law have incorporated such incentives, including Indiana, Pennsylvania, New Hampshire and Michigan. Montana, which is about to become the 29th state to extend Medicaid, also plans to include such incentives.

“People are looking for some creative ways to pass Medicaid expansion and incentivizing healthy behaviors is pretty palatable to both conservatives and liberals,” said Maia Crawford, program officer of the Center for Health Care Strategies. “It’s a potential win-win because of the potential for cost savings and health improvement.”

But getting them to participate in incentive programs can be challenging. For example, an Idaho program that offered a $100 voucher to entice Medicaid recipients to lose weight or quit smoking attracted less than 2 percent of eligible adults after two years.

Among the biggest obstacles is simply getting the word out to enrollees, Crawford said. But there are other issues, too: Poor people are less likely to understand how the incentives work and to face transportation and other barriers to get to doctor appointments or educational classes that are part of the program.

‘Long Way To Go’ To Learn What Works

Little is actually known about what types of incentives get people’s attention or help change their behavior, said Jean Abraham, associate professor of health policy and management at the University of Minnesota. It’s not clear, for instance, whether rewards are more effective in prodding people to take a concrete step, such as getting a colonoscopy or a mammogram, rather than in changing long-term behaviors, such as smoking. “We have a long way to go to understand what’s most effective,” she said.

The health law sought to get answers to some of those questions by including $85 million to test incentives in 10 state Medicaid programs.

States started the studies in 2012 and 2013 and some are struggling to get participants. Connecticut, for instance, has enrolled only half of the 6,000 people it sought for a smoking cessation program. The program pays Medicaid recipients as much as $350 in gift cards over a year for participating in smoking cessation counseling, using a counseling phone line and having a breathalyzer test showing they haven’t recently smoked. The $10 million, three-year study will compare that group’s health costs against those of a control group of Medicaid recipients who smoke but received no help.

Other states that received funding are California, Hawaii, Minnesota, New York, Nevada, New Hampshire, Montana, Texas and Wisconsin.

Separate from the health law, one of the largest incentives program is New Mexico Medicaid’s Centennial Rewards, which gives most of the state’s 600,000 recipients the chance to earn points to buy health care items.

They gain points each time they engage in a healthy behavior, such as getting a checkup or seeing a dentist. So far, only about 45,000 have registered and only half of those have redeemed points for gift cards.

New Mexico officials say they are not disappointed. “It is not only a new program for us, but a new concept for most Medicaid programs,” said Medicaid spokesman Matt Kennicott.

‘I’ve Never Felt This Good’

Juarez, 57, of Las Cruces, said the program has motivated her to walk every day at the mall where she works as a hair stylist and helped bring down her blood sugar levels.

“I’ve never felt this good,” she said. “This program motivates me to do more — it’s not so much the money as it’s the improvement in my body.”

Charles Milligan, who until last month was senior vice president of Presbyterian Health Plan in New Mexico, another Medicaid plan, said he’s seen an increase in members seeking preventive care, such as diabetes screenings and prenatal care. “The rewards program helps us engage with our members,” he said. Still, only about 30,000 of their 200,000 members have registered for it.

Iowa has also faced challenges getting Medicaid enrollees to complete the wellness exam and health risk assessment survey — even though some will have to pay a $5 or $10 monthly Medicaid premium if they don’t. About 19,500 of the state’s 125,000 enrollees have faced the potential penalty. Of those, about a third completed the wellness exam and assessment.

“The goal is to get people involved and to take a more active role in their own health and we are impressed with what we have achieved,” said Andria Seip, Iowa Medicaid’s Affordable Care Act policy manager.

Hodgins, who enrolled in Iowa Medicaid in January, said he’s glad his community health center advised him about the wellness exam and health survey —not because it saved him money but because he found out that he had high cholesterol and blood sugar, which he’s now working to bring under control.

“I’ve been blessed with decent health for 57 years,” said Hodgins, who recently started a delivery company and doesn’t mind the state prodding him to get examined. “I have to be responsible for my own health. That’s my obligation.”