ATLANTA — Dr. Alluri Raju, a native of India, vividly remembers how his ethnicity prompted concern and discrimination in the southwest Georgia town of Richland. Doctors there hesitated to grant the family practitioner and general surgeon privileges to the local hospital when he arrived in 1981.

“I guess they wanted to cut me off so that I wouldn’t be a competitor,” he recalled.

Yet, in the 37 years Raju has been practicing in Richland, more than 20 doctors have come and gone and he’s the only physician left — not just in Richland, but in all of Stewart County and neighboring Webster County, an area roughly half the size of Rhode Island with a population of more than 8,000.

“Today, I’m it,” he said. And his patients, he said, treat him with respect — and not as a foreigner.

Stories like Raju’s are the common thread for many immigrant doctors in the United States.

The American Medical Association said that, as of last year, 18 percent of practicing physicians and medical residents in the U.S. in patient care were born in other countries. Georgia’s percentage of foreign-born doctors is similar, at 17 percent.

Yet President Donald Trump’s focus on securing U.S. borders and restricting immigration — and the bitter arguments between the national political parties on the issue during midterm campaigns — have sown concerns about opportunities for foreign-born doctors.

Many of these doctors, like Raju, work in rural areas that are desperate to attract medical professionals. Yet those areas are often reliable supporters of Trump and his strict immigration policies. A recent national poll found that immigration is the top concern for Republican voters.

Some health care experts say Trump’s tough stance could make it harder for rural areas such as Richland to relieve critical physician shortages.

Georgia’s Republican lawmakers have considered legislation in recent years that opponents say would have restricted the rights of some immigrants. And Republican candidates for governor here campaigned in the primary this year on cracking down on illegal immigrants, though advocates for that position say bias is not the motivation, but rather the need for border security.

Raju’s patients say they don’t see any problem in seeking care from an immigrant. Raju has been treating Willie Hawkins, a retired road worker, for 30 years, as well as his mother and his sister.

Sometimes, Hawkins said with a smile, he has to ask the nurse what the doctor just said.

“You know, he talks a little funny,” said Hawkins, 66. “But who cares?”

Maybe when Raju first came here to practice, people were a bit skeptical, Hawkins recalled. Many had never met someone from India before, he said. “But today it just doesn’t matter,” he said.

Willie Hawkins says he doesn’t care that his physician, Dr. Alluri Raju, is an immigrant.(Credit: Katja Ridderbusch)

Foreign-born doctors are vital to the national health system. The U.S. is grappling with a doctor shortage that’s expected to grow to as many as 120,000 physicians by 2030, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges.

Even now, primary care doctors are relatively scarce in certain areas of the country. Georgia has a few counties without any doctors at all, and many counties lack a pediatrician or an OB-GYN.

These immigrants help fill some of the gaps, especially in primary care, said Dr. William Salazar of Augusta University’s Medical College of Georgia, who came to the U.S. from Colombia. And rural Georgia has a higher percentage of immigrant doctors than do urban areas, said Jimmy Lewis of HomeTown Health, an association of rural hospitals mostly in Georgia.

“Foreign-born doctors go to places no one wants to go,” said Dr. Gulshan Harjee, a Tanzanian-born physician who co-founded the Clarkston Community Health Center, a free clinic serving mainly immigrants and refugees in metro Atlanta.

Patients’ Bias

Several foreign-born doctors here recalled awkward interactions with patients, occasionally experiencing bias.

“When they think you’re different, they think you’re not as smart, and think they won’t understand what you’re saying,” said Salazar. “You develop skills to overcome that.’’

But patients overall are getting used to people from other countries, he added.

Saeed Raees, a pharmacist originally from Pakistan who co-founded the Clarkston clinic, said that “you’ll run into a small minority who don’t want to be seen by a foreign-born doctor or a Muslim doctor.”

Physicians from predominantly Muslim countries face increased pressure after the Trump administration tightened its visa and immigration policies. Several doctors said that their visa applications take longer than before or are on hold, and re-entry into the U.S. after traveling was difficult.

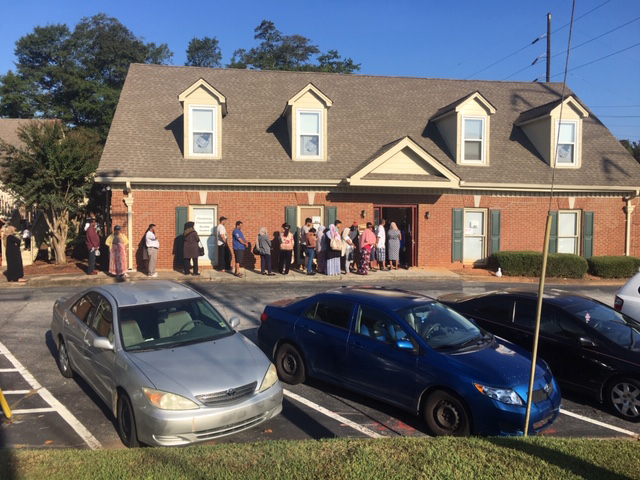

Patients line up outside the Clarkston Community Health Center near Atlanta on a recent Sunday morning. The free clinic serves many immigrants. (Andy Miller for KHN)(Andy Miller for KHN)

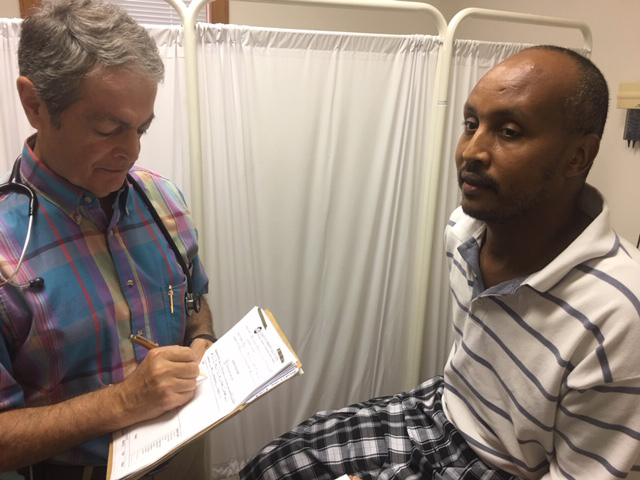

Syrian-born Dr. Omar Akhras treats a political refugee from Ethiopia, Fuad Abdi Limo, at the Clarkston Community Health Center. The free clinic serves immigrants and refugees in metro Atlanta’s highly diverse DeKalb County.(Andy Miller for KHN)

Nearly half of Muslim physicians in the U.S. felt more scrutiny at work compared with their peers, and many said they experienced discrimination in the workplace, according to a study by Dr. Aasim Padela at the University of Chicago. Nearly a tenth of the physicians surveyed reported that patients had refused their care because they were Muslim.

There is also acceptance.

Dr. Buthena Nagi, a native of Libya, is employed as a hospitalist at Navicent Health in Macon. Nagi, 40, completed her residency at Morehouse School of Medicine in Atlanta in 2015. But to stay in the country she has to meet immigration criteria.

Most foreign physicians complete their residency in the U.S., typically on a student visa. To remain beyond that, U.S. immigration law requires them to practice in a medically underserved area for at least three years. Afterward, they can apply for a green card and, eventually, American citizenship.

Nagi wears a hijab — a traditional head covering for many Muslim women — with her scrubs, and sometimes patients and colleagues ask her about it.

“I then explain that this is part of my religion,” she said. “And once the dialogue kicks in, the fear dies down, and people seem to understand that I’m not an alien from outer space.”

In metro Atlanta’s highly diverse DeKalb County, about 75 percent of the patients at the free Clarkston health center are immigrants, refugees or migrant workers. Up to 30 languages are spoken there. Co-founder Harjee said she speaks “only six.”

Sameera Vadsariya, 37, said through an interpreter that she loves the services there. She was born in India and is here on a visa. She has no health insurance, so the free services are worth the long wait for treatment.

Most of the volunteer doctors at the Clarkston clinic are foreign-born, said Harjee. “This is a passion for them. They want to give back.’’

Opportunity Lost

Belsy Garcia Manrique also wants to play a role.

At age 7, she left her home in Zacapa, Guatemala, and headed north through Mexico with her mother and sister. It was a two-week odyssey — a combination of walking and driving — up to the southern tip of Texas. Her father, Felix, who had come to the U.S. two years earlier seeking political asylum, met them and drove the family to his home in Georgia.

For many years, she dreamed of being a doctor, hoping to treat Spanish-speaking patients in the parts of northwest Georgia where she was raised.

U.S. immigration policy, however, blocked her path to medical school. She was not a legal resident. Most states, including Georgia, prevented undocumented immigrant children like Garcia Manrique from qualifying for in-state tuition at public universities.

Belsy Garcia Manrique arrived in the U.S. from Guatemala at age 7. Although she didn’t have legal authority to stay here, President Barack Obama’s executive order creating the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program made it possible for her to go to medical school.(Courtesy of Belsy Garcia Manrique)

But Garcia Manrique caught a break when President Barack Obama issued an executive order six years ago that created the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program. DACA offered more than 800,000 undocumented immigrants brought to the U.S. by their parents a chance to stay without fear of deportation.

From 2012 to 2016, medical schools from California to Massachusetts accepted roughly 100 DACA students, whose families hailed from Mexico, Pakistan, Venezuela and other countries. Garcia Manrique applied to nearly 40 schools. The Stritch School of Medicine at Loyola University Chicago, the first medical school to accept DACA students, was the only one that offered her admission.

Shortly after taking office in 2017, Trump rescinded DACA, a move that has become the subject of ongoing legal and political battles. If the law stands, Garcia Manrique will be allowed to stay in the U.S. But if it’s overturned, she and DACA medical trainees won’t be allowed to renew their work permits.

Garcia Manrique is finishing medical school and applying for a residency program to train in family medicine. Only two Georgia medical programs — at Emory University and Morehouse College — said they would consider a DACA recipient. She applied to both.

Of her 50 applications, Garcia Manrique received interview offers from nearly a dozen programs, including ones in Illinois, California and Washington. She hasn’t heard from the ones in Georgia.

And these days she isn’t sure if the Georgia she knew, and the Georgia she loved, is a place where she’d feel welcome.

“After a certain time of being looked down upon, being told ‘no,’ going the extra mile to get the same benefits, you get tired of that,” Garcia Manrique said. “I’ve seen many immigrants who have talent in the South move out. Why not be somewhere where you’re wanted?”