Opponents of aid-in-dying laws are claiming a small victory. They won the attention of Congress this week in their battle to stop a growing movement that allows terminally ill patients to get doctors’ prescriptions to end their lives.

The Republican-led effort on Capitol Hill to overturn the District of Columbia’s aid-in-dying law appeared to have died Friday. But advocates worry the campaign will catalyze a broader effort to fully ban the practice, which is legal in six states and being considered in 22 more.

“The D.C. legislation has catapulted the issue of medical aid in dying onto the federal agenda at a time when Congress has the power to enact a ban on this end-of-life care option nationwide — even criminalizing the practice in the six states where this option is currently authorized,” warned Jessica Grennan, national director of political affairs and advocacy for Compassion & Choices, which supports right-to-die laws.

“If that happens, it will set the end-of-life care movement back to the last century,” Grennan said.

Despite the apparent defeat this week, both sides agree that the debate on Capitol Hill, featuring a Republican moral protest, could be only a taste of what’s to come.

In a vote that hewed closely to party lines, the Republican-controlled House Oversight Committee on Monday approved a bill that would knock down D.C.’s law, which won approval from the mayor and City Council in December. While D.C.’s law mirrors those passed in other states, Congress has unique power to intervene in D.C.’s affairs. Under the Home Rule Act of 1973, Congress has 30 legislative days to overturn any law D.C. passes.

“It’s of deep, personal moral conviction that I stand in opposition” to D.C.’s law, said Rep. Jason Chaffetz of Utah, who chairs the committee, in Monday’s hearing.

Chaffetz appears to have lost round one. Republicans in the House and Senate introduced joint resolutions attempting to block D.C.’s law, but the bills needed to pass the full House and Senate and gain President Donald Trump’s signature by Friday. Trump has declined to take a public stance on the matter.

Because Congress didn’t complete those steps this week, D.C.’s law successfully passes the congressional review period, Rep. Eleanor Holmes Norton, D.C.’s non-voting representative, announced in a press release Friday.

But “our defense of the Death with Dignity Act is only beginning,” Norton said.

That’s because Chaffetz has threatened to launch a second attack on the bill this spring, when Congress approves D.C.’s budget. The Death With Dignity Act calls for spending $125,000 in local money to build a database tracking the assisted-dying program. The law is set to take effect Oct. 1, at the beginning of the fiscal year, but only after the money is approved, according to D.C. mayoral spokeswoman Susana Castillo.

Dr. David Stevens, CEO of the Christian Medical & Dental Associations, which opposes medical aid in dying, said the Republicans’ effort to overturn D.C.’s law may still have broader impact.

“As representatives and senators become more educated about the dangers of physician-assisted suicide,” Stevens said, “I wouldn’t be surprised” if members of Congress introduce laws to “prohibit or at least more closely regulate” the practice.

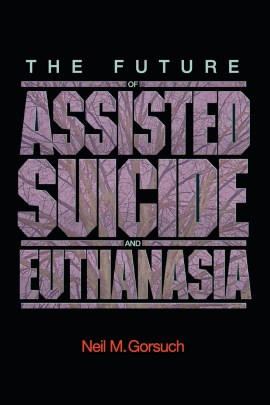

(Courtesy of Amazon.com)

If Congress passes such a law, the only hope for advocates such as Grennan “would be for the Supreme Court to intervene,” she said. But she noted that Trump’s pick for the Supreme Court, Neil Gorsuch, a federal appellate judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit, has published a book against aid-in-dying efforts. The book, she said, notes “the Supreme Court’s power to overturn the state medical aid-in-dying laws.”

Away from Capitol Hill, the aid-in-dying movement has gained steam: The practice is legal in Oregon, Washington, Vermont, Colorado, California and Montana.

Energized by victories in California and Colorado last year, aid-in-dying supporters are pushing ahead to battlegrounds nationwide. So far this year, 21 states have introduced aid-in-dying legislation, according to Compassion & Choices. And in South Dakota, proponents are trying to get the practice approved through a ballot initiative.

Hawaii, Maryland and Maine appear the most likely to pass new legislation this year, said Peg Sandeen, executive director of the Death With Dignity National Center, another national advocacy group.

But opponents have beaten back similar measures in many states in recent years. And in Alabama, South Dakota and New York, they have gone on the offensive, introducing bills to preemptively outlaw the practice or prohibit insurance from paying for the lethal drugs.

Chaffetz, who is leading the charge against D.C.’s law, has enraged Democrats and D.C. officials, who accuse him of overreaching his power by meddling in local affairs. But Chaffetz and fellow House Republicans at Monday’s vote said moral concerns trump local autonomy.

“Only God gets to decide” when a person’s life ends, declared Rep. Paul Mitchell, a Michigan Republican, during the debate.

Republican Sen. James Lankford of Oklahoma, who introduced the Senate resolution blocking the bill, also made a legal argument, citing a 1997 law passed under President Clinton that bans the use of federal money for physician-assisted death. Because of that law, Medicare and the Department of Veterans Affairs do not pay for the lethal drugs, so patients must pay out-of-pocket or use private or state-funded insurance. Lankford challenged D.C. to show that its assisted-dying program wouldn’t conflict with that law.

Advocates dismissed that argument. Sandeen, of the Death With Dignity National Center, said D.C.’s program will not use any federal money to help people die. She called the legal argument a “red herring effort,” aimed at distracting attention from politicians’ true reasons for trying to strike down D.C.’s law.

“I’d rather that they said, ‘For religious purposes, I disapprove of this law,'” she said.

This story has been updated to reflect the end of Congress’s review period.

KHN’s coverage of end-of-life and serious illness issues is supported by The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.