When the U.S. Supreme Court in 2012 ruled that states could decide for themselves if they would expand Medicaid eligibility, many thought states were left with a yes or no proposition. Simple.

Except nothing is ever simple when it comes to either the Affordable Care Act or Medicaid, the federal-state partnership that provides health care to America’s poor. Some states want to expand Medicaid, but in their own way. Lucky for them, there is a process that enables them to do so.

Medicaid programs across the states are far from identical. For one, the federal-state dollar matches vary a great deal (from a 73 percent federal to 27 percent state ratio in a poor state like Mississippi in fiscal 2013 to 50-50 for states such as Wyoming, Washington, California and Connecticut). Then, beyond certain minimum thresholds, states also diverge quite a bit in who qualifies for Medicaid, how their health care is delivered, paid for, organized and what services are covered.

While a state’s matching contribution is largely determined by the per capita income in that state, all those other program variations are the result of waivers granted after negotiations with the federal government (by way of the Department of Health and Human Services with assistance from the Office of Management and Budget). If the federal government approves, states can depart from the Medicaid statute in specified respects.

This is hardly a rare event. In the nearly 49 years since Congress passed Medicaid, every single state has been granted these waivers, most of them several times over. These waivers are the instrument most responsible for why Medicaid programs are so different across states.

Expansion Question

Now, the waivers are very much front and center as states determine if they want to participate in the ACA’s Medicaid expansion, which extends Medicaid benefits to poor, mostly childless adults. The big inducement to expanding Medicaid eligibility is that the federal government will pay 100 percent of Medicaid expenses for the expansion population through the end of 2016. After that, the federal match will eventually taper to 90 percent.

Twenty-two states plus the District of Columbia agreed to the expansion without asking for waivers, but the governors in Arkansas and Iowa wanted the federal government to allow changes in their Medicaid programs — including permission to use Medicaid monies for the expansion population to purchase private insurance on the new state insurance exchanges — before they were willing to consent to the expansion.

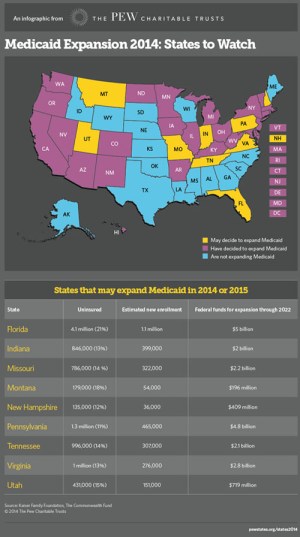

HHS agreed to Iowa’s and Arkansas’s waivers last year, which enables the Obama administration to count them among the expansion states. Michigan has an application pending. Pennsylvania is holding hearings now on its proposed waiver application. New Hampshire, Virginia, Indiana and a few other states seem likely to file waiver applications this year as well. (see infographic)

The waivers are technically called “demonstration waivers,” to convey the intention of giving states the ability to tinker with their Medicaid programs in innovative ways intended to lead to improvements in cost efficiencies and delivery of health care. “It was a way to test different approaches in Medicaid programs,” said Teresa Coughlin, a senior fellow at the Urban Institute.

Waiver Uses

Waivers are not unique to the Medicaid program. They have been part of the Social Security Act for decades. The Medicaid statutes were passed as an amendment to the act.

In the early days, Medicaid waivers were used for relatively small changes in the Medicaid programs, for example, experiments in health care delivery methods in particular regions of their states. Eventually, though, waivers grew in scope to sometimes encompass a state’s whole Medicaid program. In the 1980s, for example, a number of states, including Tennessee and Arizona, used waivers to convert their entire Medicaid programs to a managed care system. Because so many states were using waivers for managed care or for long-term nursing home care, separate waivers were eventually created for those areas of change.

(States can make modifications that don’t depart from federal law through state plan amendments, a far less rigorous process.)

Some states have also used the waiver process to extend Medicaid eligibility or to cover more health services. States, including Arizona, have also used waivers to reduce eligibility or benefits but not below certain federal minimums.

Any program changes from waivers carry a big caveat: They can’t cost more money, at least as far as the federal government’s contributions are concerned. Or if they do, the state has to identify ways to offset increased spending. The five-year waivers can be renewed for three-year terms, but the waiver programs must remain revenue neutral.

Looking at Efficiency

In their waiver applications, states often claim that their modifications will not cost more thanks to new efficiencies they will achieve to save money. States have also moved money from the funds they received from the federal government for uncompensated health care under the argument that improving Medicaid coverage would reduce the number of uninsured people who show up at hospitals in need of care.

Granting waivers is at the sole discretion of the secretary of HHS, but as Matt Salo, executive director of theNational Association of Medicaid Directors, said, the budget neutrality requirement gives the secretary a lot of leeway. “Cost neutrality is kind of in the eye of the beholder,” Salo said. “Anybody knows that a five-year projection is fraught with imperfections.”

States can, with permission, backtrack on changes they made in previous waiver applications, and, of course, they can simply let earlier changes expire when the waiver does. One state’s waiver doesn’t necessarily mean that another state can win approval to do the same thing, although they often do.

In granting Iowa and Arkansas their recent waivers, HHS indicated that it would be friendly to similar proposals from other states, but only a limited number of them. In part, Salo said he suspects that is because of HHS lack of capacity to handle many waiver requests at once. “I don’t think HHS has the physical bandwidth to negotiate with 50 different states over 50 different Medicaid programs,” he said.

“The waiver process is cumbersome, and it is difficult and it is time-consuming,” said Vern Smith, the one-time director of Michigan’s Medicaid program who is now a principal manager with Health Management Associates, a health policy consulting and research firm. The process usually takes months, sometimes longer. It is mainly a process of negotiation between the state and HHS.

According to Smith, states usually don’t file their applications until they have already largely reached agreement with HHS, and applications that were negotiated usually result in waivers.

Easier Process

Despite the federal government’s track record of ultimately approving state waivers, the National Association of Medicaid Directors has said a quicker, less arduous process would make it easier for states to adopt innovative practices.

HHS already has improved the transparency of the waiver process and standardized practices. Some of the states that have recently gone through the process say the changes have helped.

“We have found this new level of standardization very helpful in understanding what documents and procedures a state needs to develop and complete, and the expected timeframes,” said Jennifer Vermeer, director of Iowa’s Medicaid.