To contain soaring Medicaid costs, about a dozen cash-strapped states are kicking off their new budget years by reducing payments to doctors, hospitals and other health care providers that treat the poor.

That worries some health care experts who say the cuts, most of which went into effect July 1 or very soon within the month, could exacerbate a shortage of physicians and other providers participating in Medicaid.

“Further depressing payment rates can only worsen the situation,” said Sara Rosenbaum, chair of the health policy department at George Washington University. She said some of the states cutting rates — such as South Carolina — already have severe Medicaid physician shortages.

More On Medicaid Payment Cuts

S.C. Doctors Fear 5% Medicaid Cut May Cause Patients To Lose Access

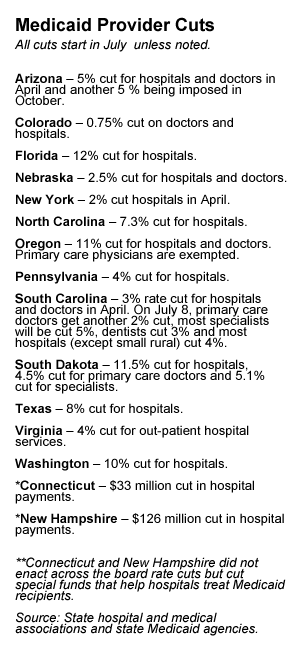

Besides South Carolina, other states that are reducing Medicaid payments to physicians beginning in July are Colorado, Nebraska, Oregon and South Dakota. Arizona, which cut rates in April, will impose another cut in October. States reducing payments to hospitals include Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Nebraska, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Texas, Virginia and Washington. (New York cut hospital payment rates in April).

In March, California approved a 10 percent Medicaid cut to doctors and hospitals, but because of an existing lawsuit, those reductions are pending and will need federal approval.

The payment cuts, which require federal approval, are part of a larger effort by states to reduce the cost of Medicaid, typically the largest- or second-largest expenditure after education. In some states, dental services and other optional benefits have gone under the knife. And many states are requiring enrollees to sign up for private Medicaid managed care plans.

Insurers and employers have their own concerns about the payment cuts. They say trimming the rates will prompt providers to raise their prices for patients who have private insurance. “It’s always a concern that when providers get less from Medicaid, that they will shift the costs to private insurance so families and employers pay more,” said Robert Zirkelbach, a spokesman for America’s Health Insurance Plans, an industry group.

Medicaid, a joint state-federal health care program, serves more than 50 million low-income and disabled people. Under the health care law, more than 16 million additional people will become eligible starting in 2014, with the federal government picking up most of the cost.

To entice more physicians to accept Medicaid patients, the law raises rates for primary care doctors in 2013 and 2014 to match those paid by Medicare, the federal health program for the elderly. States, on average, currently pay Medicaid providers about 72 percent of what Medicare pays.

Medicaid enrollment shot up during the economic downturn, but $100 billion from the federal stimulus package helped states pay the tab. However, that funding ended June 30, and now “states are struggling with what they can do,” said Laura Tobler, a policy analyst at the National Conference of State Legislatures. The health law bars states from restricting eligibility for the program.

Nearly half of the states cut provider payments in the fiscal year that ended in June, according to the National Association of State Budget Officers.

But the latest cuts are among the deepest ever, say provider groups and state officials.