Tucked into the new tax law is a provision that offers companies a tax credit if they provide paid family and medical leave for lower-wage workers.

Many people support a national strategy for paid parental and family leave, especially for workers who are not in management and are less likely to get that benefit on the job. But consultants, scholars and consumer advocates alike say the new tax credit will encourage few companies to take the plunge.

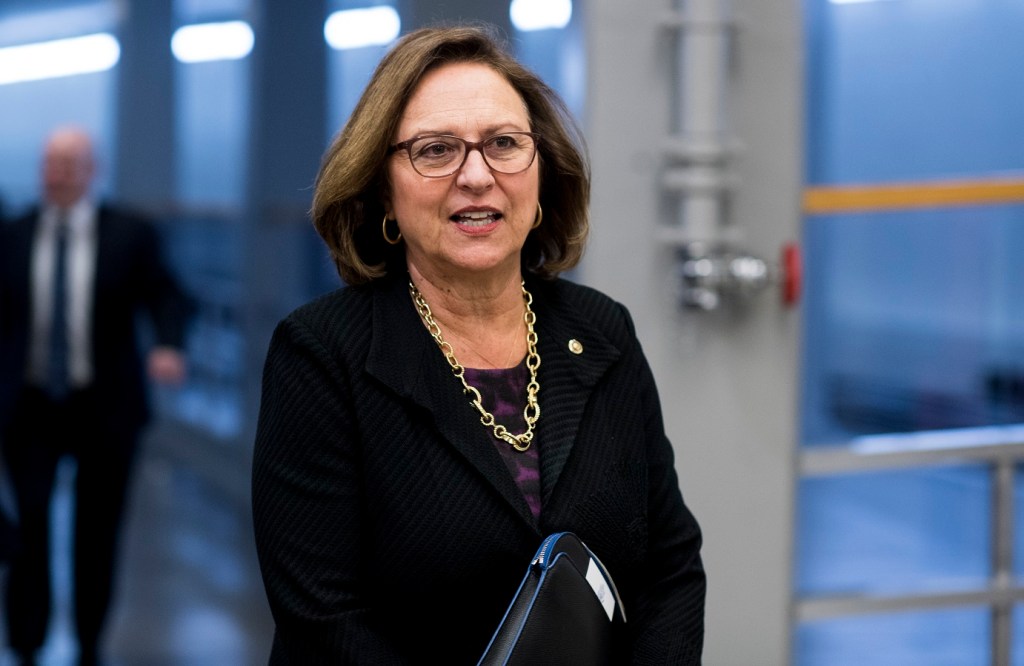

The tax credit, proposed by Sen. Deb Fischer (R-Neb.), is available to companies that offer at least two weeks of paid family or medical leave annually to workers, but two key criteria must be met. The workers must earn less than $72,000 a year and the leave must cover at least 50 percent of their wages.

If contributing at the half-wage level, a company receives a tax credit equal to 12.5 percent of the amount it pays to the worker. The tax credit will increase on a sliding scale if the company pays more than 50 percent of wages. It could go up to a maximum credit of 25 percent of the amount the employer paid for up to 12 weeks of leave.

Payments to full- and part-time workers taking family leave who’ve been employed for at least a year would be eligible for the employer’s tax break. But the program, which is designed to test whether this approach works well, is set to last just two years, ending after 2019.

Aparna Mathur, a resident scholar in economic policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute, says the new tax credit sidesteps a pitfall for Republicans. They are wary of any legislation mandating that employers provide paid leave. The tax credit also is appropriately aimed at lower-wage workers who are most likely to lack access to paid leave, said Mathur, who co-authored a recent report on paid family leave.

But it’s not a big enticement.

“Providing this benefit is a huge cost for employers,” Mathur said. “It’s unlikely that any new companies will jump on board just because they have a 12.5 to 25 percent offset.”

That view is shared by Vicki Shabo, vice president for workplace policies and strategies at the National Partnership for Women & Families, an advocacy group, who said it will primarily benefit workers at companies already offering paid family leave. The new tax credit “just perpetuates the boss lottery,” she added.

Heather Whaling said her 22-person public relations company probably qualifies for the new tax credit, but she doesn’t think it’s the right approach. Whaling, the president of Geben Communication in Columbus, Ohio, already offers paid leave. The company provides up to 10 weeks of paid leave at full pay for new parents. Four employees have taken leave, and by divvying up their work to other team members and hiring freelancers they’ve been able to get by.

“It is an expense, but if you plan and budget carefully it’s not cost-prohibitive,” she said.

The tax credit isn’t big enough to provide a strong incentive to provide paid leave, said Whaling, 37. Besides, “having access to paid family leave shouldn’t be luck of the draw, it should be available to every employee in the country.”

Still, the tax credit may be appealing to companies that have been considering adding a paid family and medical leave benefit, said Rich Fuerstenberg, a senior partner at benefits consultant Mercer.

By defraying some of the cost, the tax credit could help “tip them over” into offering paid leave, he said. But “I’m not even sure I’d call it the icing on the cake,” Fuerstenberg said. “It’s like the cherry on the icing.”

Only 15 percent of private-sector and state and local government workers had access to paid family and medical leave in 2017, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ National Compensation Survey. Eighty-eight percent had access to unpaid leave, however.

Under the federal Family and Medical Leave Act, employers with 50 or more workers generally must allow eligible employees to take unpaid leave for up to 12 weeks annually for specified reasons. These include the birth or adoption of a child, caring for your own or a family member’s serious health condition, or leave for military caregiving or deployment. An individual’s job is protected during such leaves.

A tax credit that can be claimed at the end of the year is unlikely to encourage small businesses to offer paid family and medical leave, said Erik Rettig, an expert on family leave policies at the Small Business Majority, which advocates for those firms on national policy.

“It isn’t going to help the family business that has to absorb the costs of this employee while they’re gone,” Rettig said.

A better solution, according to Shabo and others, is to provide a paid family leave benefit that’s funded by employer and/or employee payroll contributions. Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.) and Rep. Rosa DeLauro (D-Conn.) last year reintroduced such legislation. Their bill would guarantee workers, including those who are self-employed, up to 12 weeks of family and medical leave with as much as two-thirds of their pay.

A handful of mostly Democratic states — including California, New Jersey, Rhode Island and New York — have similar laws in place, and a program in the District of Columbia and Washington state will begin in 2020.

“We know from states that this approach works for both employees and their bosses,” Shabo said.