UVA Medical Center treated Heather Waldron in 2017 for complications from an intestinal malformation. The hospital sued her for $164,000 after she discovered her insurance had lapsed. That was more than twice what a commercial insurer would have paid for the same care.(Griffin Pivarunas for KHN)

Editor’s Note: This series was a finalist for the 2020 Pulitzer Prize in Investigative Journalism.

Heather Waldron and John Hawley are losing their four-bedroom house in the hills above Blacksburg, Va. A teenage daughter, one of their five children, sold her clothes for spending money. They worried about paying the electric bill. Financial disaster, they say, contributed to their divorce, finalized in April.

Their money problems began when the University of Virginia Health System pursued the couple with a lawsuit and a lien on their home to recoup $164,000 in charges for Waldron’s emergency surgery in 2017.

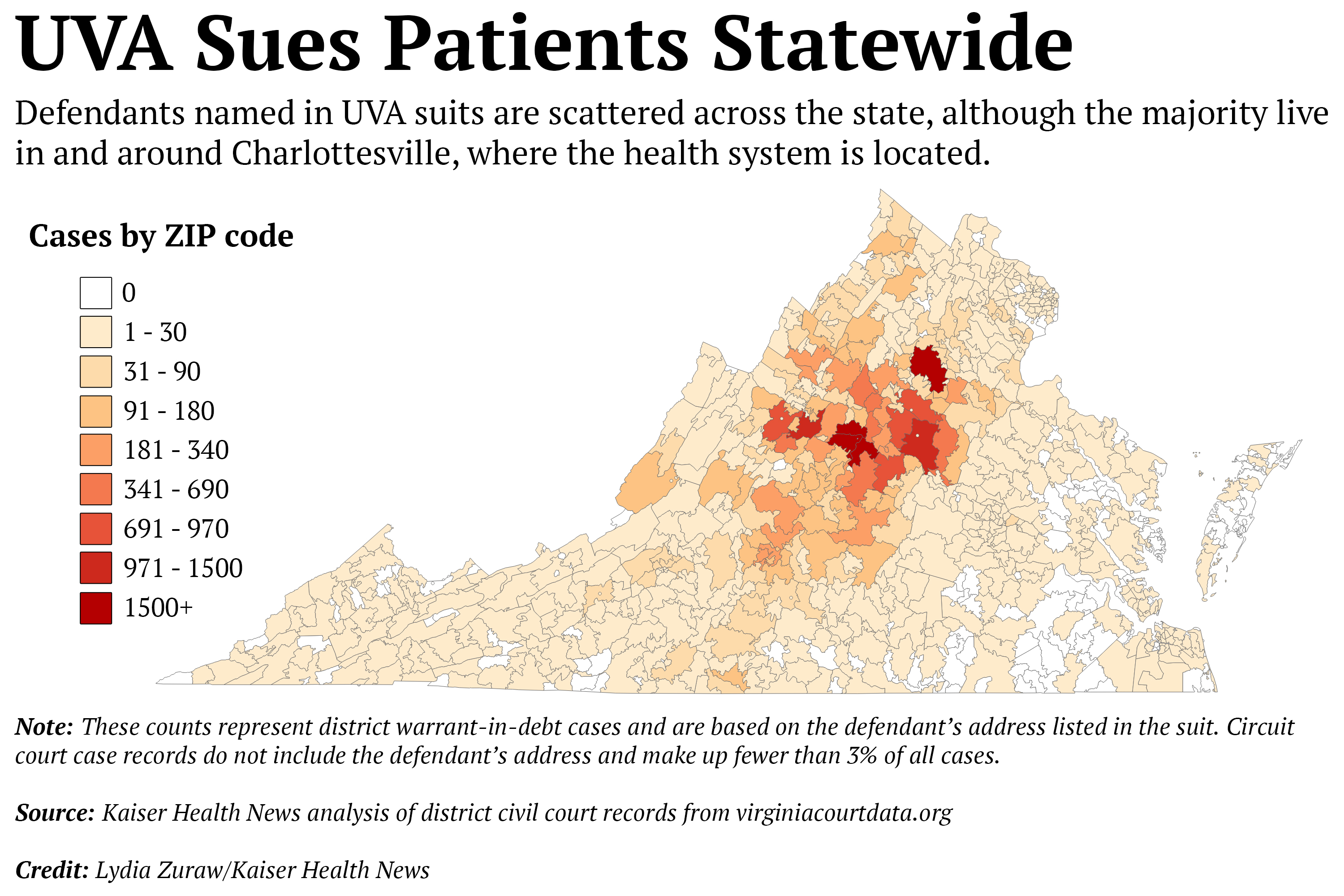

The family has lots of company: Over six years ending in June 2018, the health system and its doctors filed 36,000 lawsuits against patients seeking a total of more than $106 million, seizing wages and bank accounts, putting liens on property and homes and forcing families into bankruptcy, a Kaiser Health News analysis has found.

Unpaid hospital bills are a leading cause of personal debt and bankruptcy across the nation, with hospitals from Memphis to Baltimore criticized for their role in pushing families over the financial edge. But UVA stands out for the scope of its collection efforts and how persistently it seeks payment, pursuing poor as well as middle-class patients for almost all they’re worth.

KHN’s findings, based on court records, documents and interviews with hospital officials and dozens of patients, show UVA:

- Sued patients for as much as $1 million and as little as $13.91, and garnished thousands of paychecks, largely from workers at lower-pay employers such as Walmart, where UVA took wages more than 800 times.

- Seized $22 million over six years in state tax refunds owed to patients with outstanding bills, most of it without court judgments, under a program intended to help state and local governments collect debts.

- Sued about 100 patients every year who also happened to be UVA Health System employees and filed thousands of property liens over the years, from Albemarle County all the way to Georgia.

- Dunned some former patients an additional 15% for legal costs, plus 6% interest on their unpaid bills, which over years can add up to more than the original bill.

- Has the most restrictive eligibility guidelines for patient financial assistance of any major hospital system in Virginia. Savings of only $4,000 in a retirement account can disqualify a family from aid, even if its income is barely above the poverty level.

The hospital ranked No. 1 in Virginia by U.S. News & World Report is taxpayer-supported and state-funded, not a company with profit motives and shareholder demands. Like other nonprofit hospitals, it pays no federal, state or local taxes on the presumption it offers charity care and other community benefits worth at least as much as those breaks. Democratic Gov. Ralph Northam, a pediatric neurologist, oversees its board.

UVA defended the institution’s practices as legally required and necessary “to generate positive operating income” to invest in medical education, new facilities, research and the latest technology. They point to the Virginia Debt Collection Act of 1988, which requires state agencies to “aggressively collect” money owed.

“Sending unpaid bills to a collection agency or pursuing a civil claim is a last resort,” said UVA Health System spokesman Eric Swensen. Two years ago, he said, the health system limited lawsuits to cases in which patients owe more than $1,000. “For the vast majority of patients, we are able to agree upon workable payment plans without filing a legal claim,” he said.

In addition, UVA is “making a comprehensive review” of its charity care rules and “considering policies to provide additional financial assistance to low-income patients not covered by our existing charity care policies,” he said.

Swensen declined to discuss individual cases, saying the hospital was bound by patient confidentiality. UVA Health CEO Pamela Sutton-Wallace declined an interview request. A spokeswoman for Northam did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Though there is no national data on hospital debt collection, UVA’s pursuit of patients goes beyond that of a number of institutions. Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore has sued patients 240 times a year on average, according to a May report in The Baltimore Sun. UVA, by comparison, often sues that many former patients in a week and averages more than 6,000 cases annually, court data show.

Private, nonprofit Yale New Haven Health System files liens only if a bill is over $10,000 and then only if the property is worth at least $300,000, a spokesman said. Falls Church, Va.-based Inova Health says it does not file liens on patient homes or garnish wages.

Tenet Healthcare, a national, for-profit chain whose stock trades on Wall Street, says it does not sue uninsured patients who are unemployed or who lack significant assets other than their house.

Waldron learned after her UVA hospitalization that a computer error involving a policy bought on healthcare.gov had led her insurance to lapse.(Griffin Pivarunas for KHN)

Industry standards are few and vague. The American Hospital Association says its members follow Internal Revenue Service guidelines, which merely require hospitals to have a financial assistance policy and to make “reasonable efforts” to determine whether a patient qualifies for help before initiating collections.

Patients find themselves unable to pay UVA bills for many reasons: They are uninsured or sometimes have short-term coverage that does not pay for treatment of preexisting illnesses. Or they are out-of-network, or have a “high-deductible” plan — increasingly common coverage that can require patients to pay more than $6,000 before insurance kicks in. Virginia’s Medicaid expansion, effective this year, covers families with low income but is still projected to leave hundreds of thousands uninsured.

Patients also have trouble because, like many U.S. hospitals, UVA bills people lacking coverage at rates far higher than what insurance companies pay on behalf of members. In addition, experts say such bills often have little connection to the cost of care. Insurers obtain huge discounts off hospital sticker prices — 70% on average in UVA’s case, according to documents it files with Medicare.

UVA offers uninsured patients 20% off to start and an additional 15% to 20% if they pay promptly, Swensen said. Few are able to do that. Patients are subject to collections and lawsuits if they do not pay or arrange to do so within four months, he said.

The $164,000 billed to Heather Waldron for intestinal surgery was more than twice what a commercial insurer would have paid for her care, according to benefits firm WellRithms, which analyzed bills for Kaiser Health News using cost reports UVA files with the government. Charges on her bill included $2,000 for a $20 feeding tube.

UVA would not disclose basic information about patient lawsuits, liens and garnishments. Reporters reconstructed the hospital’s practices by talking directly with patients, analyzing court documents and hospital bills and observing the legal process in court. They gathered records in Charlottesville, where the UVA Health System is located, to supplement a courts database compiled by the nonprofit Code for Hampton Roads, which works to improve government technology.

The picture that emerges is of a trusted institution whose practices violate its stated public mission, with little accountability or redress for its patients.

Waldron, 38, an insurance agent and former nurse, appreciates the treatment she received for an intestinal malformation that almost killed her. But, she said, “UVA has ruined us.”

‘Here For A Hospital Case?’

UVA sues so many patients that District Court Judge William Barkley doesn’t announce the cases as he takes the bench each Thursday in the historic brick courthouse in Charlottesville. On this day, he waves a thick stack of litigation at defendants, asking, “Is anybody here for a hospital case?” Nobody needs to ask which hospital.

A recent NPR report noted that nonprofit Mary Washington Healthcare, in Fredericksburg, Va., had 300 cases in court in one month. (Following that report the hospital announced that it would suspend the practice of suing patients for unpaid bills.)

Barkley’s court often handles 300 UVA suits in a week, data shows.

The court often operates like a UVA billing office. UVA sends collections representatives, not lawyers, who sit near the judge’s bench. They give patients two weeks to commit to an interest-free payment plan, according to courtroom meetings witnessed by a reporter. Otherwise, “we’re already going to be reviewing it for garnishment,” a UVA official tells a car accident victim. With bills often in the tens of thousands of dollars, even the five-year, interest-free plans are unaffordable, patients said.

Swensen said patients in court would have already received “four to five” bills over several months and notifications about potential financial assistance.

Zann Nelson — who is 70, lives in Reva, Va., and was sued by UVA for $23,849 a few years ago — is a rare patient who fought back. Admitted with a newly diagnosed uterine cancer, she was bleeding and in pain when she signed an open-ended payment agreement. In court, she argued it was so vague as to be unenforceable. (C-Ville Weekly, a local paper, wrote about her case in 2014.)

She lost. The judge, according to court records, said that Nelson had “the ability to decline the surgery” if she didn’t like the terms of the deal. She lived with a lien on her farm until she managed to pay off the debt.

Zann Nelson, who fought back in court against a UVA Health System lawsuit, lost her case after a judge said she had “the ability to decline the surgery” needed for cancer if she didn’t agree to UVA’s terms.(Jay Hancock/KHN)

‘Can’t Afford To Go Back’

UVA Medical Center, the flagship of UVA Health System, earned $554 million in profit over the six years ending in June 2018 and holds stocks, bonds and other investments worth $1 billion, according to financial statements. CEO Sutton-Wallace earns a salary of $750,000, with bonus incentives that could push her annual pay close to $1 million, according to a copy of her employment contract, obtained under public information law.

Yet UVA offers financial assistance that’s more limited than any other major health system in Virginia, according to an analysis of policies at organizations including Inova, Sentara Healthcare, Riverside Health and Carilion Clinic.

To qualify for help, UVA patients must earn less than 200% of federal poverty guidelines ($34,000 for a couple) and own less than about $3,000 in assets, not counting a house, according to the hospital’s website and guidelines UVA files with the state.

Carilion Clinic, by contrast, provides aid to families with income up to 400% of poverty guidelines and assets of less than $100,000, other than a house. If bills at Riverside Health exceed household income over 12 months, the hospital forgives the whole amount.

Sentara slashed lawsuit volume by using software to rule out patients who were unlikely to pay, said spokesman Dale Gauding. “We write off a lot of bad debt rather than put someone through a judgment they can’t pay and an additional black mark on their credit,” he said.

The only other policy in Virginia similar to UVA’s is that of VCU Health, a sister state hospital system with the same income and asset guidelines. In July, VCU started offering help to some patients with “catastrophic” and “prohibitively expensive” bills who don’t otherwise qualify, a spokesman said.

“We are considering those updates,” Swensen said of VCU’s changes. He noted that for the most recent fiscal year UVA approved almost 10,000 applications for charity care. Most of the patients who qualify pay nothing beyond a $6 copay, he said.

Carolyn Davis got injections at UVA Health System to treat back pain that her insurer did not cover. UVA rejected her application for financial assistance because her husband, a Hardee’s cook, had $6,000 in a Hardee’s retirement account.(Jay Hancock/KHN)

UVA sued Carolyn Davis, 55, of Halifax County, for $7,448 to pay for nerve injections to treat back pain that she hadn’t realized would be out-of-network.

Her husband is a cook at Hardee’s, taking home $500 to $600 a week, she said. UVA refused their application for financial assistance because his Hardee’s 401(k) balance of $6,000 makes them too well-off, she said.

“We don’t have that kind of money,” Davis said. The hospital insisted on a monthly payment of $75. She was meeting it by charging it to her credit card at 22% interest.

Charges for Davis’ treatment were about twice what a commercial insurer would have paid, according to an estimate by WellRithms.

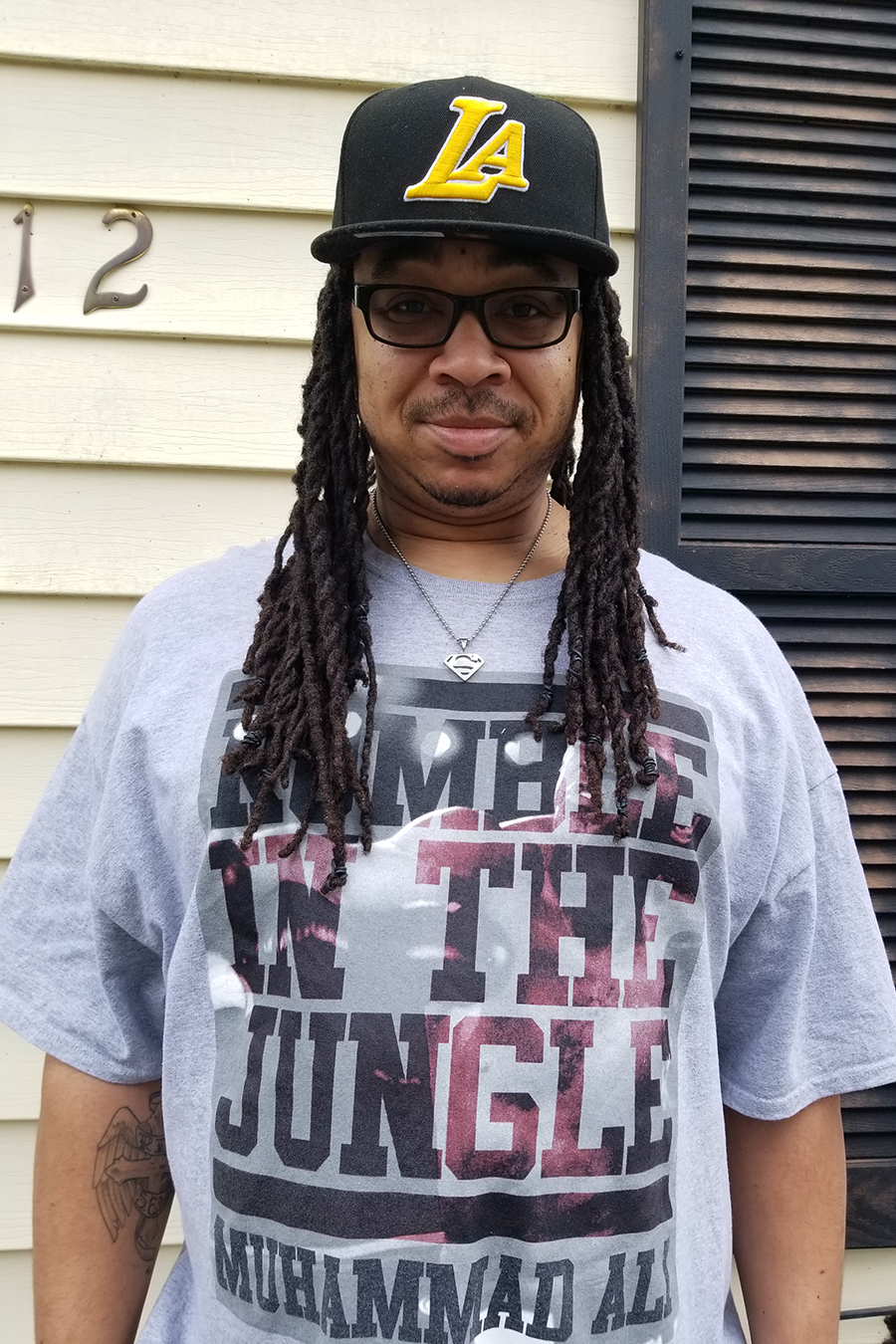

Sometimes patients who are prepared to pay cash for UVA treatment find they can’t afford the charges. Wayne Williams, 43, of Charlottesville, is a custodian at a community college. He was uninsured but feared he had strep throat last year.

Wayne Williams, a community college custodian, went to the UVA emergency room for a sore throat and came out with a $6,931 bill.(Courtesy of Wayne Williams)

“I thought they were going to give me some antibiotics,” he said.

Instead, UVA’s emergency department gave him a CT scan, a bill for $6,931 and, when he didn’t pay, a lawsuit. UVA did give him a 30% discount based on his financial circumstances, he said — meaning the sore throat would cost about $4,800.

WellRithms calculated that a commercial insurance company would have paid $992 for the care Williams received, which would have covered costs and generated a profit.

Leigh Ann Beach, 37, of Palmyra, experienced how differently hospitals treat those who cannot pay after hurting her ankle in a bike accident.

Rising premiums left her uninsured when she fell off a bike and hurt her ankle last year. Her husband works in construction to provide for their family with seven children. A rainy 2018 washed out working days and his income. They couldn’t afford their $667 monthly insurance premium.

Sentara Martha Jefferson Hospital, which first treated her, canceled the entire $4,650 bill in light of her family’s income, her paperwork shows. UVA, where she got surgery and metal implants, sued her for $9,505 and rejected her request for financial help.

A UVA representative said she could sell some acreage from her small rural home to pay the bill, she said. She limps and is in pain, but “I can’t afford to go back,” she said.

Resorting To Bankruptcy

When Jesse Lynn, 42, of Orange County, bought short-term coverage as a bridge between policies, he and wife Renee didn’t realize the plan considered Jesse’s old back problems a preexisting illness, and therefore would not pay for treatment.

After back surgery at Culpeper Medical Center, a UVA affiliate, he came out with a bill for about $230,000, Renee Lynn said.

The surgeon reduced his portion of the charges — from $32,000 to $4,500, which they thought was reasonable. They asked for a similar break or a payment delay from UVA. “We are not a lending institution,” the billing office told her, she said.

The Lynns decided bankruptcy was their only option.

“I probably see at least a couple a month,” said Marshall Slayton, a Charlottesville bankruptcy lawyer, holding up a new file. “This is the third case this week.”

UVA said it doesn’t foreclose on primary residences. But often a UVA lawsuit leads to home loss because patients’ credit is downgraded and they cannot keep up with hospital payment plans and mortgages.

Property liens do give UVA a claim on the equity in patients’ homes.

“We see a lot of them,” said Tina Merritt, a partner with True North Title in Blacksburg. “And a lot of people don’t even know until they go to sell the property.”

It took Priti Chati, 62, of Roanoke six years to pay a $44,000 UVA bill for brain surgery and have a home lien removed last year, court records show. She had had a pre-Obamacare policy that did not cover preexisting illness. The health system seized bank funds intended for her daughters’ college costs, she said. She sold jewelry and borrowed from friends, eventually paying more than $70,000 including interest, she said.

Paul Baker, 41, of Madison County ran a small lawn service and with his wife owes more than $500,000 for treatment after their truck rolled over. He is grateful to UVA “for saving my life,” he said. But he is “frustrated they are ultimately taking my farm” when he sells or dies, a result of UVA’s lawsuit.

Indigent Care

Swensen said the medical center gave $322 million in financial assistance and charity care in fiscal 2018. But legal and finance experts said that’s not a reliable estimate.

The $322 million “merely indicates the amount they would have charged arbitrarily” before negotiated insurer discounts, said Ge Bai, an accounting and health policy associate professor at the Johns Hopkins Carey Business School.

The figure is “based on customary reporting standards used by hospitals across the U.S.,” Swensen said.

Insurers would have paid UVA only $88 million for that care, according to an accounting of unpaid bills presented in September 2018 to the UVA Health board. Even that unpaid figure did not come out of UVA’s purse since federal and state governments provided “funding earmarked to cover indigent care” for almost all of it — $83.7 million, according to Bai.

The real, “unfunded” cost of UVA indigent care: $4.3 million, or 1.3% of what it claims, according to the document.

“That’s nothing,” given how much money UVA makes, Bai said. “Nonprofit hospitals advance their charitable mission primarily through providing indigent care.”

The hospital recorded an additional $109 million in uncollectible debts not considered indigent care, the document shows.

Nacy Sexton was close to graduation from the University of Virginia when UVA Health System blocked his enrollment because of an outstanding medical bill.(Julia Rendleman for KHN)

Nacy Sexton, who is in his 30s and lives outside Richmond, hoped he might get a break on his medical bills as a student enrolled at Virginia. He was close to graduation in 2015 when he was hospitalized for lupus. After he was unable to cover the reduced bill offered by the hospital, the university blocked his enrollment, a notice he received from student financial services shows.

“The university places enrollment holds on student accounts for many reasons, including unpaid tuition and medical bills,” said university spokesman Wesley Hester. This semester the university has “active holds” on 20 students because of unpaid medical center bills, which might or might not block their attendance depending on when the hold was placed, he said.

Sexton still has about $4,000 to go on a bill that he said was more than $30,000 before UVA’s discount, a fundraising campaign and other payments. He hopes to re-enroll and finish his degree in education next year.

“When you get sick, why should it affect your education?” he asked.

Shirley Perry was a registered nurse at the medical center who was “so proud of working at UVA,” said her mother, Vera Perry. She became chronically ill, lost her job and insurance, and then needed treatment from her former employer. UVA sued her for $218,730 plus $32,809 in legal fees. She died last year at age 51, with a UVA lien on her townhouse. It was auctioned off on Aug. 7 at the Albemarle County Courthouse.

For Heather Waldron, the path from “having everything and being able to buy things and feeling pretty good” to “devastation” began when she learned after her UVA hospitalization that a computer error involving a policy bought on healthcare.gov had led to a lapse in her insurance.

She is now on food stamps and talking to bankruptcy lawyers. A bank began foreclosure proceedings in August on the Blacksburg house she shared with her family. The home will be sold to pay off the mortgage.

She expects UVA to take whatever is left.

Methodology

KHN analyzed Virginia civil case records from both the district and circuit courts from July 2012 through June 2018, based on the date a case was filed. These case records were acquired from Ben Schoenfeld, a volunteer for Code for America, a nonprofit focused on improving government technology. Schoenfeld compiles court records that are available directly from Virginia’s court system (from both circuit and district courts) and posts them on the website VirginiaCourtData.org.

The Circuit Courts of Alexandria and Fairfax do not use the statewide case management system and are not included in this analysis.

The online circuit court cases do not include the amount for which the plaintiff sued. KHN went to the Albemarle Circuit Court (where most of the UVA circuit cases were filed) and looked up each of over 900 cases by hand to obtain the dollar amount, which totaled over $60 million.

The online district court cases do include a principal amount sought in a “Warrant in Debt” case. However, if the case is settled or dismissed, the principal amount is zero. Therefore, KHN’s reporting of the total for which UVA has sued its patients during this period is likely a low estimate.

KHN focused on district cases that were “Warrant in Debt” cases and circuit cases that were “Complaint — Catch-all” or “Contract Action.” UVA sues to recover patient debt from all three categories. For cases brought by the University of Virginia, the plaintiff names (as entered by the court) vary widely: “University of Virginia,” “Rectors and Visitors of UVA” or just “UVA” are some examples. We included cases that mentioned the UVA Physicians Group and Health Services Foundation (although these were much less prevalent). In some cases, the UVA Medical Center was named specifically; in others, it was not. KHN analyzed cases brought by the university whether or not the case specifically mentioned the medical center, knowing that some cases omit this detail. We took a random sample of 30 “Warrant in Debt” cases from the Albemarle District Court in 2017 that were filed by “Rectors and Visitors” but did not specify the medical center. We looked up the original records at the courthouse; each one was related to the medical center.

KHN also found several 2012 cases filed in the Albemarle Circuit Court by UVA that were not in the public data available online, which suggests that the data is not necessarily complete.

KHN contacted UVA directly on multiple occasions. We filed several public records requests for the number of cases involving medical debt and the total amount sought, as well as the total amount recovered. Each time our request was denied.