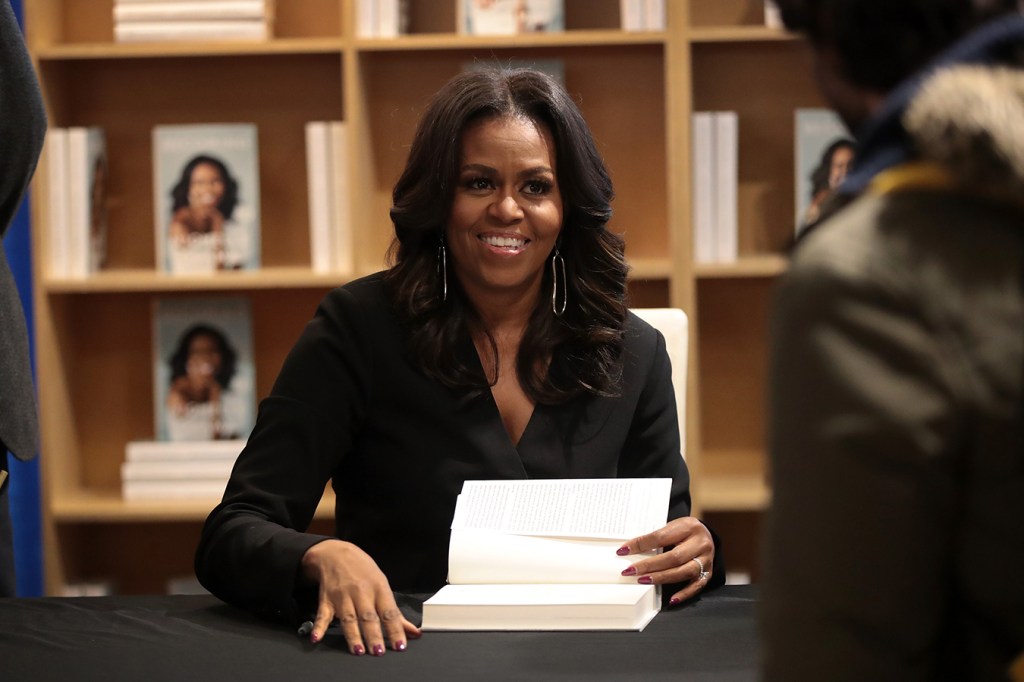

Miscarriage is “lonely, painful, and demoralizing,” Michelle Obama writes in her new memoirs. Yet, by some estimates, it ends as many as 1 in 5 pregnancies before the 20-week mark.

The former first lady’s disclosure that she and former President Barack Obama suffered from fertility issues, including losing a pregnancy, has sparked conversations about miscarriage, a common but also commonly misunderstood loss.

Psychologists say that ignorance can contribute to the emotional and psychological toll of losing a pregnancy, isolating women and their partners and leaving loved ones uncertain of how to comfort them.

Nearly five years later, Becky Shaw of Woodbridge, Va., still remembers texting her friend after her miscarriage, just asking if she was around to talk. Within a couple of minutes, her friend called. “I don’t even remember what she was saying, but she made me laugh,” Shaw said.

The trauma began early in her first pregnancy. Shaw, now 35, had experienced some bleeding when she and her husband showed up for her checkup on Christmas Eve in 2013. The nurse performing the ultrasound was wearing a Santa hat.

“You can tell when something’s wrong,” Shaw said. “She’s just staring at the screen. And then she was finally like, Can you hold your breath?”

The nurse struggled to find the baby’s heartbeat, which she said was dangerously low and could stop. For weeks, Shaw felt “like a time bomb.” She miscarried in early January.

Shaw said it is important for a woman like Obama to speak out about her miscarriage. “It just makes people feel less alone,” she said. “My miscarriage wrecked me, and I had the most supportive friends and the best doctors.”

Becky Shaw, of Woodbridge, Va., with her husband, Ben, and son, Parker. Shaw’s first pregnancy ended in a miscarriage in 2014, and Parker – their “rainbow baby,” as babies born after pregnancy loss are often called – was born the next year.(Ruby Eliason Photography)

Many grief counselors are praising Obama for illuminating — and normalizing — miscarriage, helping families cope with their own loss.

“What a gift,” said Helen L. Coons, a clinical health psychologist specializing in women’s behavioral health at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

Miscarriage, or the loss of a pregnancy before 20 weeks, is so common that Americans often stay quiet about their pregnancies until after the first trimester, when the majority of miscarriages occur. Improvements in early pregnancy detection and the use of fertility treatments have also increased the likelihood that couples learn they have miscarried, whereas they once might not have even known they were pregnant.

The risks are greater for black women, who are more likely to experience pregnancy loss than white women. (Black infants are also much more likely to die during their first year of life, according to recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

For such a common occurrence, though, much about miscarriage is widely misunderstood. A 2015 survey found that many people do not understand its causes, with more than a fifth of respondents saying they believed lifestyle choices (such as smoking or drinking alcohol) are the most common cause. In reality, most miscarriages are caused by genetic problems.

Other factors that respondents wrongly identified as potential causes included lifting heavy objects (believed by 64 percent); having had a sexually transmitted disease (41 percent); and even getting into an argument (21 percent).

It is uncommon to find out the cause of one’s miscarriage, and women frequently blame themselves. The survey also found that 47 percent of those who had experienced a miscarriage reported feeling guilty; 41 percent reported feeling alone.

Some women are also left with worries that they are infertile, a fear that can stoke identity issues for those who see themselves as destined for parenthood.

Psychologists say it is important as well to acknowledge the grief of the partner or spouse, who may process the emotions differently but also has experienced his or her own loss.

Isolation can exacerbate those feelings, including some women’s belief that “their body let them down,” said Coons of the University of Colorado.

Nancy Molitor, a clinical psychologist and professor at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine, said she asked herself the same question as many women when she suffered her own miscarriage, a trauma that nearly killed her: What did I do wrong?

Today, women are more likely to talk to friends and other loved ones about their miscarriages, Molitor said, helping them realize how common the events are and removing some of the stigma. But even in 1996, when she miscarried, “nobody talked about it,” she said.

She counsels women, some in their 80s or 90s, who bring up their miscarriages decades later. “There’s a wistfulness about the fact that they never talked about that,” Molitor said, adding, “You were told, move on, honey. Move on, dear. It wasn’t meant to be.”

Couples who miscarry also find themselves grappling with a grief that comes with no set rules or rituals. Stefania Patrizio of Philadelphia and her husband waited until she was 12 weeks along to tell their family and friends she was pregnant. She was showing by the time she miscarried at around 20 weeks.

“There were a lot of people who didn’t know how to handle it, because it’s a different type of grief, it’s a different type of — I guess I’ll say death, because it’s not someone you knew,” she said. “It was a grief of a dream.”

Conceiving her daughter — who was born a year after her miscarriage, almost to the day — did not ease her fears. “I didn’t want to talk about it. I didn’t want to get excited,” said Patrizio, now 34. “Even just the click click click of the [ultrasound] machine would give me so much anxiety.”

Psychologists emphasize the importance for women recovering from a miscarriage to build a support network.

Coons recommends that pregnant women reach out to at least one or two people close to them to discuss any fears they may have. That could mean disclosing an early pregnancy to a couple of friends before revealing it publicly, so they not only can talk about their anxieties but also have loved ones ready to help should something go wrong.

Aline Zoldbrod, a Boston-based psychologist who runs SexSmart.com and has written about infertility, said those who have miscarried may find comfort from a therapist or support group, both of which can soothe the guilt and “inherent sense of defectiveness” women often feel.

Zoldbrod recommends loved ones avoid using lines like “you’ll have another one” to comfort those who have lost a pregnancy, which can come across as delegitimizing their loss. She said it can be enough to simply tell them, “I am so sorry.”

In the absence of established ceremonies, many have found peace in their own rituals or remembrances. After losing their pregnancy, Patrizio and her husband camped out together on a pullout sofa they dubbed “our island” — eating, sleeping, visiting with friends and crying.

They also traveled to Scotland, where they spent time hiking. One day, finding themselves alone by a lake, they held their own ceremony, reading a poem before throwing a few keepsakes from the pregnancy into the water.

Shaw said after finding out their baby was a girl, she and her husband named her: Cecelia.

She keeps a journal about her feelings for Cecelia, and sometimes, around the anniversary of her miscarriage, Shaw pulls out a box of cards, sonogram images and a onesie she bought on a whim while shopping with a friend, shortly after learning she was pregnant.

“I don’t want to say you move on,” Shaw said. “It’s kind of just your new normal.”

KFF Health News' coverage of these topics is supported by The David and Lucile Packard Foundation and Heising-Simons Foundation