Cars have sticker prices, ketchup bottles have nutrition facts labels and soon health plans will get coverage labels, too.

For the first time, consumers shopping for a health policy will be able to get a good idea of how much of the costs different plans will cover for three medical conditions: maternity care, treatment for diabetes and breast cancer. And because buying insurance is more complicated than buying a can of soup, the proposed insurance labels are two pages long.

However, the labels will provide pricing based on national averages and not exact numbers that consumers can expect to pay. And to begin with, only the three medical scenarios will be listed.

“Today, there’s really no way for consumers to figure what their premiums are buying,” said Sabrina Corlette, a research professor at Georgetown University’s Health Policy Institute in Washington, D.C., who is helping to produce the labels. The true value of a plan depends on what health problems a beneficiary experiences, but in most cases consumers shopping for plans have no way to compare how much of the costs of treatment the policies will cover. “It’s nearly impossible for a consumer to make apple-to-apple comparisons. It’s the Wild West,” she said.

The new “coverage facts labels” are required under the health overhaul law, which directed the National Association of Insurance Commissioners to draft them. The association gave that job to a working group made up of state insurance regulators, industry representatives and consumer advocates.

On Thursday, the group agreed to seek public comment on the draft labels and conduct consumer focus testing for additional feedback before presenting them to state insurance commissioners. Once approved, the labels will be sent to federal officials who will consider incorporating them into rules for insurance companies. The labels are part of an effort to demystify insurance terminology and costs so that consumers can better understand what they are purchasing. The law also requires that consumers receive new, easy-to-understand summary of plan benefits for consumer comparisons. The coverage labels are to be included at the end of the four-page benefits summary.

The federal rules, which were due last March, would instruct insurers to use benefit summaries and labels and are supposed to take effect next year. But developing the model format and language has proved to be complicated and taken more time.

“We want there to be as much information in the hands of consumers as possible,” said Susan Pisano, a spokeswoman for America’s Health Insurance Plans, an industry group that will be conducting consumer focus group testing, as is Consumers Union, later this month. “But we want to make sure that the information is valuable from their perspective.”

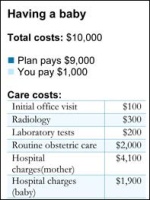

Because medical costs vary widely across the country and among providers, and the treatment regimen may also depend on individual providers, the working group opted to use national average prices for the standard treatment regimen on the labels. The labels then break down how a policy would apportion those costs.

For the breast cancer example, insurers will have to list how much patients would pay based on the national average price-for office visits, lab tests, surgery, chemotherapy, radiation treatment, prosthesis (wig), prescription drugs and mental health counseling. If a plan offers no maternity coverage, the label will show that the patient is responsible for paying the entire cost.

At first the working group was going to recommend that each health plan use prices based on their own provider contracts, said Richard Dropski, a group member and senior director for regulatory affairs at Neighborhood Health Plan in Massachusetts. That turned out to be unwieldy: even within the same plan, two nearby hospitals can charge different prices for the same procedure, he said.

A 2009 study of three California insurance policies found that patients would spend nearly $4,000 for a standard breast cancer treatment under one policy or as much as $38,000 under another even though both policies had similar deductibles and out-of-pocket limits.

The actual costs at a specific hospital may be different from the amounts listed on the coverage label, said Mila Kofman, co-chair of the working group and Maine’s superintendent of insurance. “But you will be able to look at the label and look at two different policies and figure out if you’re a diabetic or if you have baby, under which policy it is likely that more of your costs will be covered,” she said.

The law requires that all carriers selling group or individual health plans provide the benefits summaries and the three treatment labels to shoppers beginning in March 2012. There is no limit to the number of treatment coverage labels that may eventually be used.

Contact Susan Jaffe at jaffe.khn@gmail.com.