Paul Melquist of St. Paul, Minn., has a message for the people who wrote the Affordable Care Act: “Quit wrecking my health care.”

Teri Goodrich, of Raleigh, N.C., has the same complaint. “We’re getting slammed. We didn’t budget for this,” she said.

Millions of people have gained health insurance because of the federal health law. Millions more have seen their existing coverage improved.

But one small slice of the population — including Melquist and Goodrich — are unquestionably worse off. They are healthy people who buy their own coverage but earn too much to qualify for help paying their premiums. And the premium hikes that are being announced as enrollment looms for next year — in some states, increases topping 50 percent — will make their situations more miserable.

Exactly how big is this group? According to Mark Farrah Associates, a health care analysis firm, as of 2017 there were 17.6 million people in the individual market, 5.4 million of whom bought policies outside the health exchanges, where premium help is not available. Combine that with the percentage of people who bought insurance on the exchanges but earned too much (more than four times the federal poverty level, or about $48,000 for an individual) to get premium subsidies, and the estimate is 7.5 million, or 43 percent of the total individual market purchasers, according to insurance industry consultant Robert Laszewski.

And who are these people?

“They’re early retirees,” said Laszewski. “They’re people working part time who have substantial outside income. They’re people who are self-employed of any age, people who are small employers.”

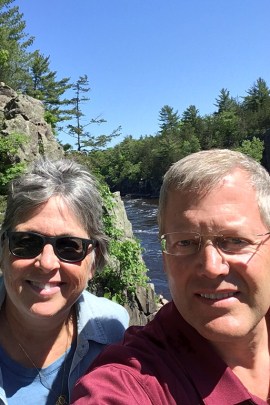

Melquist is one of those early retirees. He and his wife are both 59. He worked in the defense industry and retired at the end of 2016.

He said he always planned to retire at age 55, but ended up working longer in part because he knew health insurance costs were rising. When he did retire and sought to purchase coverage for himself and his wife, “I was shocked to find out how bad it actually was.”

Paul and Nancy Melquist of St. Paul, Minn., both 59, retired last year and were nervous about insurance costs, but he says they were “shocked to find out how bad it actually was.” (Family photo)

For a bronze-level plan with a health savings account, Melquist said, “we pay $15,000 a year” in premiums “and the first $6,550 [for health care expenses] for each of us comes out of our pocket. So basically you could be looking at $30,000 out-of-pocket before anything gets covered.”

Insurance is important, Melquist said, particularly if a catastrophic health issue were to hit either of them. In the meantime, he can still pay the bills. But he’s frustrated. “I’m not eating dog food, but I’m also not able to do stuff for my grandchildren,” he said, like help with college costs. “It’s not that my life is falling apart, but the [Affordable Care Act] has ruined a lot of things I’d like to have done.”

The good news, if there is any, for Melquist is that premiums in Minnesota are going up by only small amounts for 2018, and in some cases going down, due to a reinsurance program passed by the state legislature that will help cover the costs for some of the state’s sickest patients in the individual market. That helps keep premiums from spiking even more.

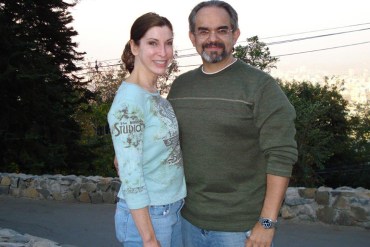

But that won’t be the case in Raleigh, where Goodrich and her husband, John Kistle, work as private consultants in the energy industry.

Goodrich, 59, and Kistle, 57, bought insurance through the ACA exchange in their state for three years. When premiums reached $1,600 per month with deductibles of $7,500 each, however, “it was just unbelievable. We decided just not to get insurance,” Goodrich said.

Eventually, they bought short-term plans that cover only catastrophic illness or injury. That insurance is not considered adequate under the ACA, so the couple could be liable for a tax penalty as well.

Teri Goodrich and her husband, John Kistle, of Raleigh, N.C., gave up their expensive marketplace health insurance and bought short-term plans that cover only catastrophic illness or injury, even though that might leave them open to penalties under the federal health law. (Family photo)

Goodrich, who volunteers to help people with their taxes in her spare time, said she has run the numbers and thinks that insurance is so expensive where she lives that the couple will be exempt from the penalty. That’s because the cheapest insurance would cost the couple more than 8.16 percent of their income. Under the health law’s provisions, the penalty does not apply above that because insurance is considered unaffordable.

“We try to be good citizens and do the right thing,” she said. “Next year, we’re trying to figure out how to make less than $64,000 so we can get subsidies.” That amount is equal to 400 percent of the federal poverty line for two people, the cutoff for premium assistance because Congress assumed those who earned more could afford to buy affordable coverage.

Sabrina Corlette, a research professor at Georgetown University who specializes in health insurance, agreed that this is a population “that faced big hikes” in premiums when the health law took effect.

But, she said, in many cases people in the individual market were previously paying artificially low premiums. Some of those old policies had substandard coverage. For others, however, the higher prices are the result of one of the fundamental changes enacted by the health law. “These are folks who were benefiting from a system that was affordable solely because insurers were able to keep sick people out,” Corlette said, adding that they are now being asked “to pay more of the true cost of health care.”

This is a population that is also more likely to vote Republican, said Laszewski, “which is one of the grand ironies now.”

Republicans in Congress and President Donald Trump have not been able to “repeal and replace” the health law. But some of their efforts are undermining it — primarily the administration’s threat to stop paying billions of dollars to insurers in subsidies help some lower-income people pay their out-of-pocket costs. The uncertainty surrounding those subsidies has led insurers to boost premiums next year by an estimated 20 percent. Those who get premium help from the government won’t have to pay more. But those who are paying the full freight will.

Also driving up premiums for next year, said Corlette, are the administration’s threats not to enforce the individual requirement for insurance and its decision to cancel most advertising and outreach for the year’s open-enrollment period that begins Nov. 1. Both of those provisions bring more healthy people into the insurance pool to help spread costs.

“One could argue that the 2014 premium increases were painful, but it was about getting us to a system that was more fundamentally fair and just,” Corlette said. “Now, it’s completely unnecessary price increases for unsubsidized folks that could so easily be avoided by a rational political system.”