Opioid settlement cash is not inherently political. It’s not the result of a law passed by Congress nor an edit to the state budget. It’s not taxpayer money. Rather, it’s coming from health care companies that were sued for fueling the opioid crisis with prescription painkillers.

But like most dollars meant to address public health crises, settlement cash has nonetheless turned into a political issue.

Gubernatorial candidates in several states are clashing over who gets bragging rights for the funds — which total more than $50 billion and are being distributed to state and local governments over nearly two decades. Among the candidates are attorneys general who pursued the lawsuits that produced the payouts. And they’re eager to remind the public who brought home the bacon.

“Scoring money for your constituency almost always plays well,” said Stephen Voss, an associate professor of political science at the University of Kentucky. It “is a lot more compelling and unifying a political argument than taking a position on something like abortion,” for which you risk alienating someone no matter what you say.

In Kentucky, Attorney General Daniel Cameron, the Republican candidate for governor, wants sole credit for the hundreds of millions of dollars his state is receiving to fight the opioid epidemic. In a post on X, formerly known as Twitter, he wrote that his opponent, former attorney general and current Democratic Gov. Andy Beshear, “filed a lot of lawsuits during his time [in] office, but in this race, there is only one person who has actually delivered dollars to fight the opioid epidemic, and it’s not him.”

However, Beshear filed nine opioid lawsuits during his tenure as attorney general, several of which led to the current payouts. At a January news conference, Beshear defended his role: “That’s where these dollars are coming from — cases that I filed, and I personally argued many of them in court.”

Polls indicate that Beshear leads Cameron ahead of the Nov. 7 election.

Christine Minhee, founder of OpioidSettlementTracker.com, who is closely following how attorneys general handle the money nationwide, said voters likely don’t know that the opioid settlements are national deals crafted by a coalition of attorneys general and private lawyers. So when one candidate claims credit for the money, his constituents may believe “he’s the sole hero in all of this.”

Candidates in other states are touting their settlement credentials, too. North Carolina Attorney General Josh Stein, a Democrat, lists securing opioid settlement funds at the top of the “accomplishments” section of his 2024 gubernatorial campaign website. West Virginia Attorney General Patrick Morrisey, a Republican gubernatorial candidate for 2024, has repeatedly boasted of securing the “highest per capita settlements in the nation” in news conferences and on social media and his campaign website.

In Louisiana, Attorney General Jeff Landry, a Republican who was recently elected governor, ran on a tough-on-crime platform, with endorsements from sheriffs and prosecutors. As attorney general, he led negotiations on dividing opioid settlement funds within the state, resulting in an agreement to send 80% to parish governments and 20% to sheriffs’ departments — the largest direct allocation to law enforcement in the nation.

It’s a common joke that AG stands for “aspiring governor,” and officials in that role often use big legal cases to advance their political careers. Research shows that attorneys general who participate in multistate litigation — like that which led to the opioid settlements and the tobacco settlement before it — are more likely to run for governor or senator.

But for some advocates and people personally affected by the opioid epidemic, this injection of politics raises concerns about how settlement dollars are being spent, who is making the decisions, and whether the money will truly address the public health crisis. Last year, more than 100,000 Americans died of drug overdoses.

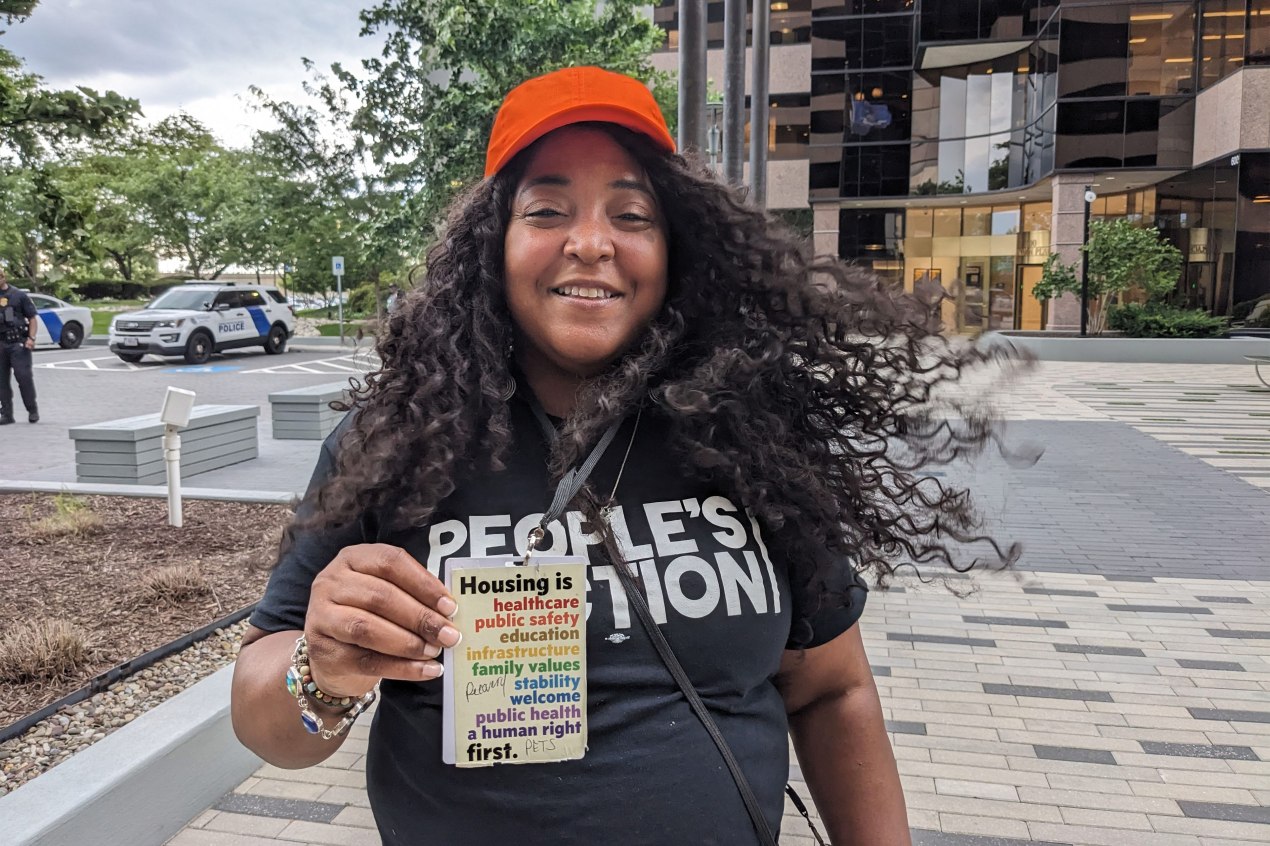

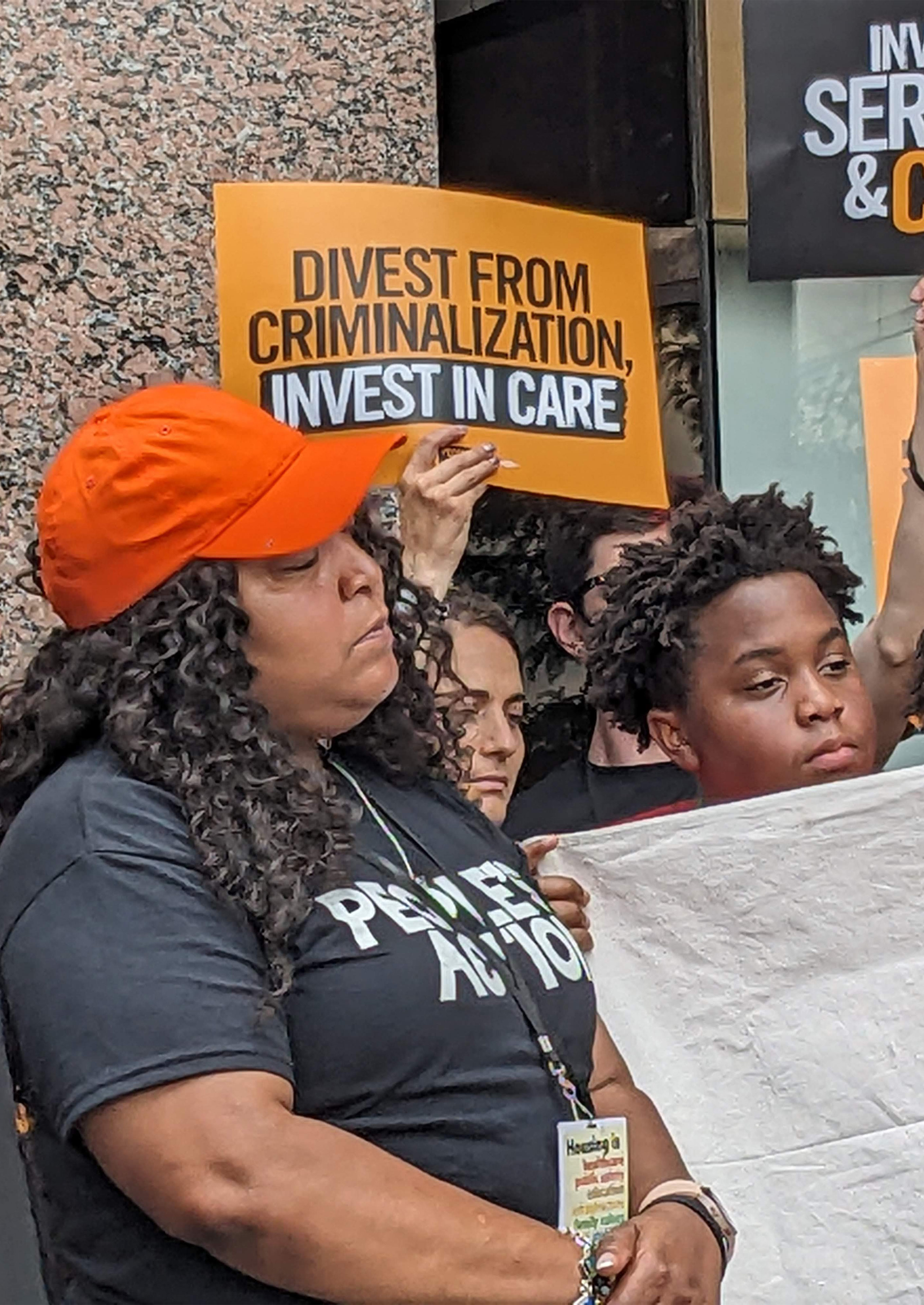

Average people “don’t really care about the bragging rights as much as they care about the ability to use that funding to improve and save lives,” said Shameka Parrish-Wright, director of VOCAL-KY, an advocacy group that champions investments in housing and health care.

“What I see in my state is a lot of press conferences and news pieces,” said Parrish-Wright, a Democrat who is active in local politics. “But what plays out doesn’t get to the people” — especially those deeply affected by addiction.

For example, when Beshear celebrated a decrease in the state’s overdose deaths, his announcement overlooked the increasing deaths among Black Kentuckians, Parrish-Wright said. And when Cameron’s appointee to the state’s opioid abatement advisory commission announced that $42 million of settlement funds were being considered to research ibogaine — a psychedelic drug that has shown potential to treat addiction — Parrish-Wright’s first thought was “most poor people can’t afford that.” To obtain it, people often have to travel out of the country.

The ibogaine announcement caused additional controversy. It’s an experimental drug, and, if approved, the $42 million allocation would be the single-largest investment from the commission, which is housed in Cameron’s agency. The Daily Beast reported that a billionaire Republican donor backing Cameron’s gubernatorial campaign stands to reap massive profits from the drug’s development.

Neither Cameron’s office nor his campaign responded to requests for comment.

Beshear’s office declined an interview request but referred KFF Health News to his previous public statements, in which he criticized the potential investment in ibogaine. He has suggested Cameron — whose campaign has emphasized support for police — is not putting his money where his mouth is.

“If you only provide $1 million to law enforcement and 42 to pharma, it doesn’t seem like you’re backing the blue. It seems like you’re backing Big Pharma,” Beshear said at a May news conference.

He also said his two appointees to the commission were caught off guard by the public announcement on ibogaine, despite their role overseeing settlement funds.

Minhee, founder of OpioidSettlementTracker.com, said she’s concerned that mixing politics with settlement funds could result in ineffective investments nationwide.

“If some of this money is going to be politicized to advance careers of attorneys general who support the war on drugs, then that is literally using monies won by death to feed into more death,” she said.

Parrish-Wright, of VOCAL-KY, said she worries that candidates — and some voters — will forget about the significance of the money once ballots are cast.

“We cannot let it fade after the election cycle,” she said.

Her solution depends in part on politics. She’s on the ballot herself Nov. 7, for a seat on Louisville’s Metro Council. If she wins, she said, she intends to keep the settlement in the public conversation.