Americans are abandoning their masks. They’re done with physical distancing. And, let’s face it, some people are just never going to get vaccinated.

Yet a lot can still be done to prevent covid infections and curb the pandemic.

A growing coalition of epidemiologists and aerosol scientists say that improved ventilation could be a powerful tool against the coronavirus — if businesses are willing to invest the money.

“The science is airtight,” said Joseph Allen, director of the Healthy Buildings program at Harvard University’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “The evidence is overwhelming.”

Although scientists have known for years that good ventilation can reduce the spread of respiratory diseases such as influenza and measles, the notion of improved ventilation as a front-line weapon in stemming the spread of covid-19 received little attention until March. That’s when the White House launched a voluntary initiative encouraging schools and work sites to assess and improve their ventilation.

The federal American Rescue Plan Act provides $122 billion for ventilation inspections and upgrades in schools, as well as $350 billion to state and local governments for a range of community-level pandemic recovery efforts, including ventilation and filtration. The White House is also encouraging private employers to voluntarily improve their indoor air quality and has provided guidelines on best practices.

The White House initiative comes as many employees are returning to the office after two years of remote work and while the highly contagious BA.2 omicron subvariant gains ground. If broadly embraced, experts say, the attention to indoor air quality will provide gains against covid and beyond, quelling the spread of other diseases and cutting incidents of asthma and allergy attacks.

The pandemic has revealed the dangerous consequences of poor ventilation, as well as the potential for improvement. Dutch researchers, for example, linked a 2020 covid outbreak at a nursing home to inadequate ventilation. A choir rehearsal in Skagit Valley, Washington, early in the pandemic became a superspreader event after a sick person infected 52 of the 60 other singers.

Ventilation upgrades have been associated with lower infection rates in Georgia elementary schools, among other sites. A simulation by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that combining mask-wearing and the use of portable air cleaners with high-efficiency particulate air filters, or HEPA filters, could reduce coronavirus transmission by 90%.

Scientists stress that ventilation should be viewed as one strategy in a three-pronged assault on covid, along with vaccination, which provides the best protection against infection, and high-quality, well-fitted masks, which can reduce a person’s exposure to viral particles by 95%. Improved airflow provides an additional layer of protection — and can be a vital tool for people who have not been fully vaccinated, people with weakened immune systems, and children too young to be immunized.

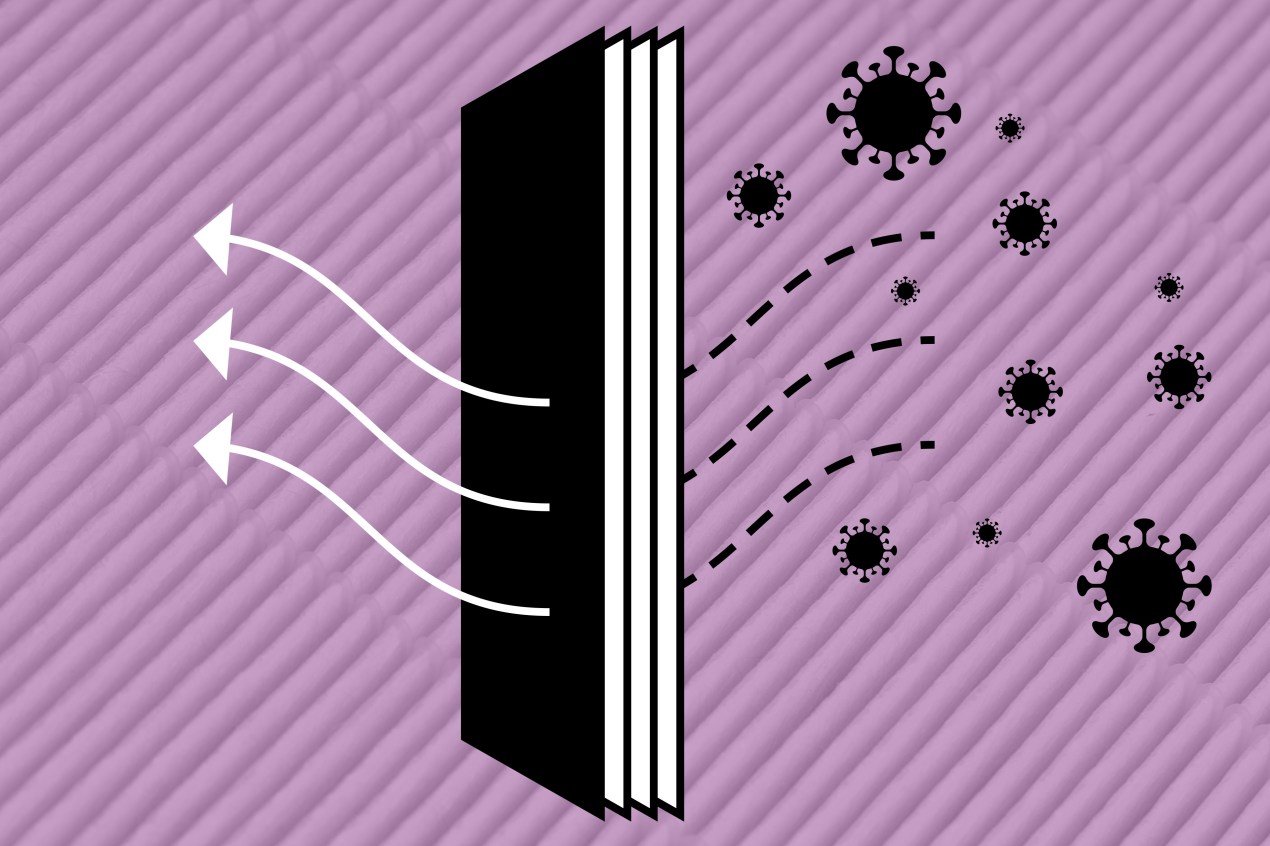

One of the most effective ways to curb disease transmission indoors is to swap out most of the air in a room — replacing the stale, potentially germy air with fresh air from outside or running it through high-efficiency filters — as often as possible. Without that exchange, “if you have someone in the room who’s sick, the viral particles are going to build up,” said Linsey Marr, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Virginia Tech.

Exchanging the air five times an hour cuts the risk of coronavirus transmission in half, according to research cited by the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy. Yet most buildings today exchange the air only once or twice an hour.

That’s partly because industry ventilation standards, written by a professional group called the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers, or ASHRAE, are voluntary. Ventilation standards have generally been written to limit odors and dust, not control viruses, though the society in 2020 released new ventilation guidelines for reducing exposure to the coronavirus.

But that doesn’t mean building managers will adopt them. ASHRAE has no power to enforce its standards. And although many cities and states incorporate them into local building codes for new construction, older structures are usually not held to the same standards.

Federal agencies have little authority over indoor ventilation. The Environmental Protection Agency regulates standards for outdoor air quality, while the Occupational Safety and Health Administration enforces indoor-air-quality requirements only in health care facilities.

David Michaels, an epidemiologist and a professor at the George Washington University Milken Institute School of Public Health, said that he’d like to see a strong federal standard for indoor air quality but that such calls inevitably raise objections from the business community.

Two years into the pandemic, it’s unclear how many office buildings, warehouses, and other places of work have been retooled to meet ASHRAE’s recommended upgrades. No official body has conducted a national survey. But as facilities managers grapple with ways to bring employees back safely, advocates say ventilation is increasingly part of the conversation.

“In the first year of the pandemic, it felt like we were the only ones talking about ventilation, and it was falling on deaf ears,” said Allen, with Harvard’s Healthy Buildings program. “But there are definitely, without a doubt, many companies that have taken airborne spread seriously. It’s no longer just a handful of people.”

A group of Head Start centers in Vancouver, Washington, offers an example of the kinds of upgrades that can have impact. Ventilation systems now pump only outdoor air into buildings, rather than mixing fresh and recirculated air together, said R. Brent Ward, the facilities and maintenance operations manager for 33 of the federally funded early childhood education programs. Ward said the upgrades cost $30,000, which he funded using the centers’ regular federal Head Start operating grant.

Circulating fresh air helps flush viruses out of vents so they don’t build up indoors. But there’s a downside: higher cost and energy use, which increases the greenhouse gases fueling climate change. “You spend more because your heat is coming on more often in order to warm up the outdoor air,” Ward said.

Ward said his program can afford the higher heating bills, at least for now, because of past savings from reduced energy use. Still, cost is an impediment to a more extensive revamp: Ward would like to install more efficient air filters, but the buildings — some of which are 30 years old — would have to be retrofitted to accommodate them.

Simply hiring a consultant to assess a building’s ventilation needs can cost from hundreds to thousands of dollars. And high-efficiency air filters can cost twice as much as standard ones.

Businesses also must be wary of companies that market pricey but unproven cleaning systems. A 2021 KHN investigation found that more than 2,000 schools across the country had used pandemic relief funds to purchase air-purifying devices that use technology that’s been shown to be ineffective or a potential source of dangerous byproducts.

Meghan McNulty, an Atlanta mechanical engineer focused on indoor air quality, said building managers often can provide cleaner air without expensive renovations. For example, they should ensure they are piping in as much outdoor air as required by local codes and should program their daytime ventilation systems to run continuously, rather than only when heating or cooling the air. She also recommends that building managers leave ventilation systems running into the evening if people are using the building, rather than routinely turning them down.

Some local governments have given businesses and residents a boost. Agencies in Montana and the San Francisco Bay area last year gave away free portable air cleaners to vulnerable residents, including people living in homeless shelters. All the devices use HEPA filters, which have been shown to remove coronavirus particles from the air.

In Washington state, the public health department for Seattle and King County has drawn on $3.9 million in federal pandemic funding to create an indoor air program. The agency hired staff members to provide free ventilation assessments to businesses and community organizations and has distributed nearly 7,800 portable air cleaners. Recipients included homeless shelters, child care centers, churches, restaurants, and other businesses.

Although the department has run out of filters, staff members still provide free technical assistance, and the agency’s website offers extensive guidance on improving indoor air quality, including instructions for turning box fans into low-cost air cleaners.

“We did not have an indoor air program before covid began,” said Shirlee Tan, a toxicologist for Public Health-Seattle & King County. “It’s been a huge gap, but we didn’t have any funding or capacity.”

Allen, who has long championed “healthy buildings,” said he welcomes the new emphasis on indoor air, even as he and others are frustrated it took a pandemic to jolt the conversation. Well before covid brought the issue to the fore, he said, research was clear that improved ventilation correlated with myriad benefits, including higher test scores for kids, fewer missed school days, and better productivity among office workers.

“This is a massive shift that is, quite honestly, 30 years overdue,” Allen said. “It is an incredible moment to hear the White House say that the indoor environment matters for your health.”