WASHINGTON — Every night, Abdullah Ibrahim retreats from the streets into a wooded stretch along the Potomac River.

As night falls and temperatures drop, he erects a tent and builds a fire beneath a canopy of pine, hemlock, and cedar trees.

He evades authorities by rotating use of three tents of different colors at three campsites. As day breaks, he dismantles his shelter, rolls up his belongings, and hides them for the next night. “They don’t see you if you’re in the woods,” the 32-year-old said. “But make sure it’s broken down by morning or they’ll find you.”

During the day, he wanders, stopping at a public library to warm up or a soup kitchen to eat. What’s important is to not draw attention to himself for being homeless.

“Police want us out of the way,” he said, dressed in a gray jacket and carrying none of his possessions. “Out of sight, out of mind.”

Ibrahim has been deliberate about blending in since August, when President Donald Trump placed the district’s police under federal control and ordered National Guard soldiers to patrol its streets. The president also ordered homeless people to leave immediately. “There will be no ‘MR. NICE GUY,’” he posted.

The Trump administration says encampment sweeps have reduced the visibility of homelessness, thereby enhancing the city. “There is no disputing that Washington, DC is a safer, cleaner, and more beautiful city thanks to President Trump’s historic actions to restore the nation’s capital,” White House spokesperson Taylor Rogers said.

While there may appear to be fewer homeless people in the nation’s capital now, they have not disappeared.

In interviews, homeless people said they are in a constant shuffle, hiding in plain sight. During the day, they stay on the move, grabbing meals at soup kitchens and resting on occasion in public libraries, on park benches, or at bus stops. At night, many unsheltered people bed down in business doorways, on park sidewalks, and on church stoops. Some ride the bus all night, while a few shelter in emergency rooms. Others find respite in the woods or flee to suburbs in Virginia or Maryland.

There are about 5,100 homeless people in Washington, D.C., including in temporary shelters, according to an early-2025 homelessness tally. After Trump ordered the crackdown on public homelessness, people living in makeshift communities scattered and are now living in the shadows. City officials estimated in August that nearly 700 homeless people were living outdoors without tents or other shelter.

As winter draws near, they are exposed to the elements and grow sicker as chronic ailments such as diabetes and heart disease go untreated. Street medicine providers say that, since the National Guard was deployed, they have faced enormous difficulty finding patients. Many caught up in sweeps have had their lifesaving medications thrown away, and they are more likely to miss medical appointments because they are constantly on the move. Street medicine providers say they can’t find their patients to deliver medication or transport them to medical appointments. The constant chaos can suck patients with mental illness and substance use deeper into drug and alcohol addiction, raising the risk of overdose.

Caseworkers report similar disruptions, saying as clients get lost, they break connections essential for obtaining housing documents, particularly IDs and Social Security cards.

District officials and health providers say this cascade will make homelessness worse, threatening public health and public safety and racking up enormous costs for the health care system.

“It was already hard locating people, but the federal presence just made it worse,” said Tobie Smith, a street medicine doctor and the executive director of Street Health D.C.

The Homeless Shuffle

Chris Jones was born and raised in Washington, D.C., but now is homeless, having been pushed out of his tent near the White House in the initial days of the federal homelessness crackdown. He said two of his tents were taken during sweeps. Now, sleeping on a sidewalk outside a church, he doesn’t bother trying to get another one. “Why? What’s the point? It’ll just get thrown away again.”

Jones, 57, has a severe knee injury that prevents him from walking some days and said he was scheduled for a knee replacement in December. He said it’s important to stay where he is — he relies on a nearby drugstore to refill his medications for bipolar disorder, diabetes, and high blood pressure. When he’s hungry, he goes to a soup kitchen for a meal or tries to get a cheeseburger and a soda from a fast-food joint across the street.

It’s important for him to stay outside the church, he said, so his case manager can find him when a permanent housing slot opens up. If it gets too cold, he said, he will cross the street and sleep in the doorway of a business, which can provide a bit more shelter. He wants to get indoors, but for now, he waits.

Since taking control of Washington’s police force, the Trump administration has ratcheted up pressure on cities and counties across the nation to clear homeless encampments under threat of arrest, citation, or detention. It has ordered or threatened similar National Guard deployments in Los Angeles; Portland, Oregon; and other cities with large homeless populations.

Rogers, the White House spokesperson, said the president is maintaining National Guard and federal law enforcement presence in the nation’s capital “to ensure the long-term success of the federal operation.” Since March, city and federal officials have removed more than 130 homeless encampments, she said, though some local homelessness experts say that number could be inflated.

The Supreme Court last year made it easier for elected officials and law enforcement to fine or arrest homeless people for living outside. Then, in July of this year, the president issued an executive order calling for a nationwide crackdown on urban camping, including a massive removal of people living outdoors and forced mental health or substance use treatment.

Trump is also spearheading an overhaul of homelessness policy, moving to slash funding for permanent housing and services for homeless people. The move would limit the use of a long-standing federal policy known as “Housing First” that offers housing without mandating mental health or addiction treatment. The National Alliance to End Homelessness warns the move risks displacing at least 170,000 people in permanent supportive housing. The Department of Housing and Urban Development paused the plan on Dec. 8 to make revisions, which it “intends” to do, federal housing officials said.

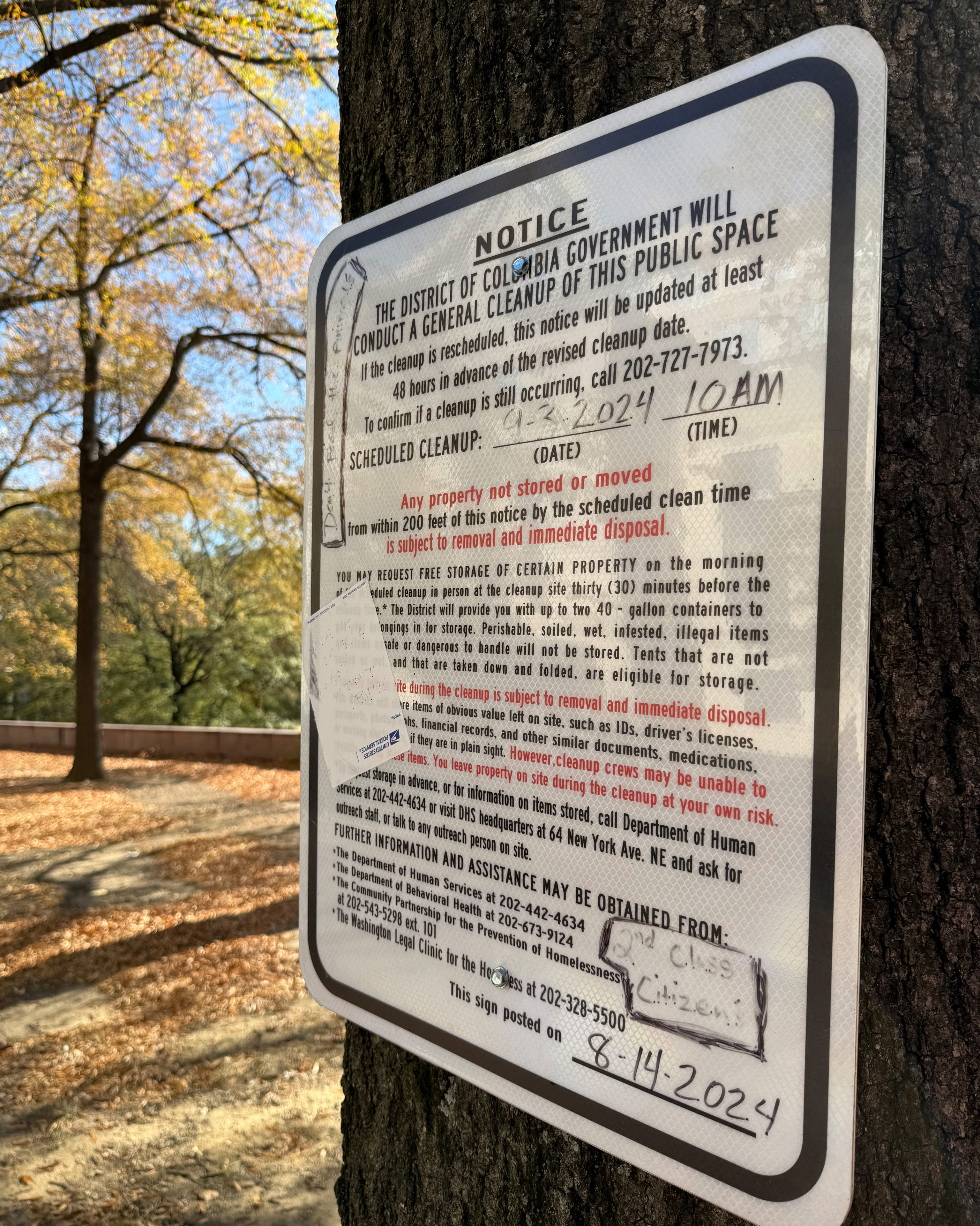

City officials say they are complying with the Trump administration’s forceful campaign against homeless people sheltering outside. Pressured by the White House, local officials said they’ve gotten more aggressive in breaking up camps. Advocates for homeless people say some of the sweeps have been conducted at night and others with little or no notice to move. City leaders believe they could be done more compassionately by offering services and shelter.

“We’ve pivoted from the notion of allowing encampments if they didn’t violate public health or safety to a position of, ‘We don’t want you in the streets,’” said Wayne Turnage, deputy mayor for District of Columbia Health and Human Services, who oversees encampment cleanups. “It’s unsafe, it’s unhealthy, and it’s dangerous.” Yet he acknowledges the encampment sweeps can waste city resources as caseworkers and street medicine providers scramble to find their clients and patients.

Advocates say the Trump administration is inciting fear and mistrust between homeless people and those working to help them while wasting taxpayer dollars used to provide care and place people into housing. There are, however, far fewer tents and large-scale encampments visible to tourists and residents.

“People found safety in those communities and service providers could find them. Now there are people with guns and flashing lights dislocating folks experiencing homelessness without notice and just throwing stuff away,” said Jesse Rabinowitz, campaign and communications director for the National Homelessness Law Center.

District officials say some people have accepted emergency shelter. But even as the city works to connect people with services and expand shelter capacity, officials acknowledge there isn’t enough permanent housing or temporary beds for everyone.

And there will be fewer places for people living outside to go.

The city, in its fiscal year 2026 budget, concentrated its homelessness funding on families, funding 336 new permanent supportive housing vouchers. Yet it cut funding for temporary housing for both families and individuals and provided no new permanent supportive housing vouchers for individuals. That means fewer housing slots for single adults, who make up most of those wandering the streets. City officials said, however, that they have slotted 260 more permanent housing units for homeless individuals or families into their construction pipeline.

Worsening Health Care

The fallout is inundating local soup kitchens with demand, including Miriam’s Kitchen in Foggy Bottom. The local institution provides hot meals, housing assistance, and warm blankets to people in need.

Caseworkers say it’s becoming increasingly difficult to help clients secure IDs and other documents needed for housing and other social services.

“I’m looking everywhere, but I can’t find people,” said Cyria Knight, a caseworker at Miriam’s Kitchen. “Most of my clients went to Virginia.”

It’s unclear how much of the district’s homeless population has fanned out to neighboring Virginia and Maryland communities. There were an estimated 9,700 homeless people in the region in January, months before Trump’s crackdown. Four of six counties around Washington saw homelessness rise from 2024, while it fell 9% in the district.

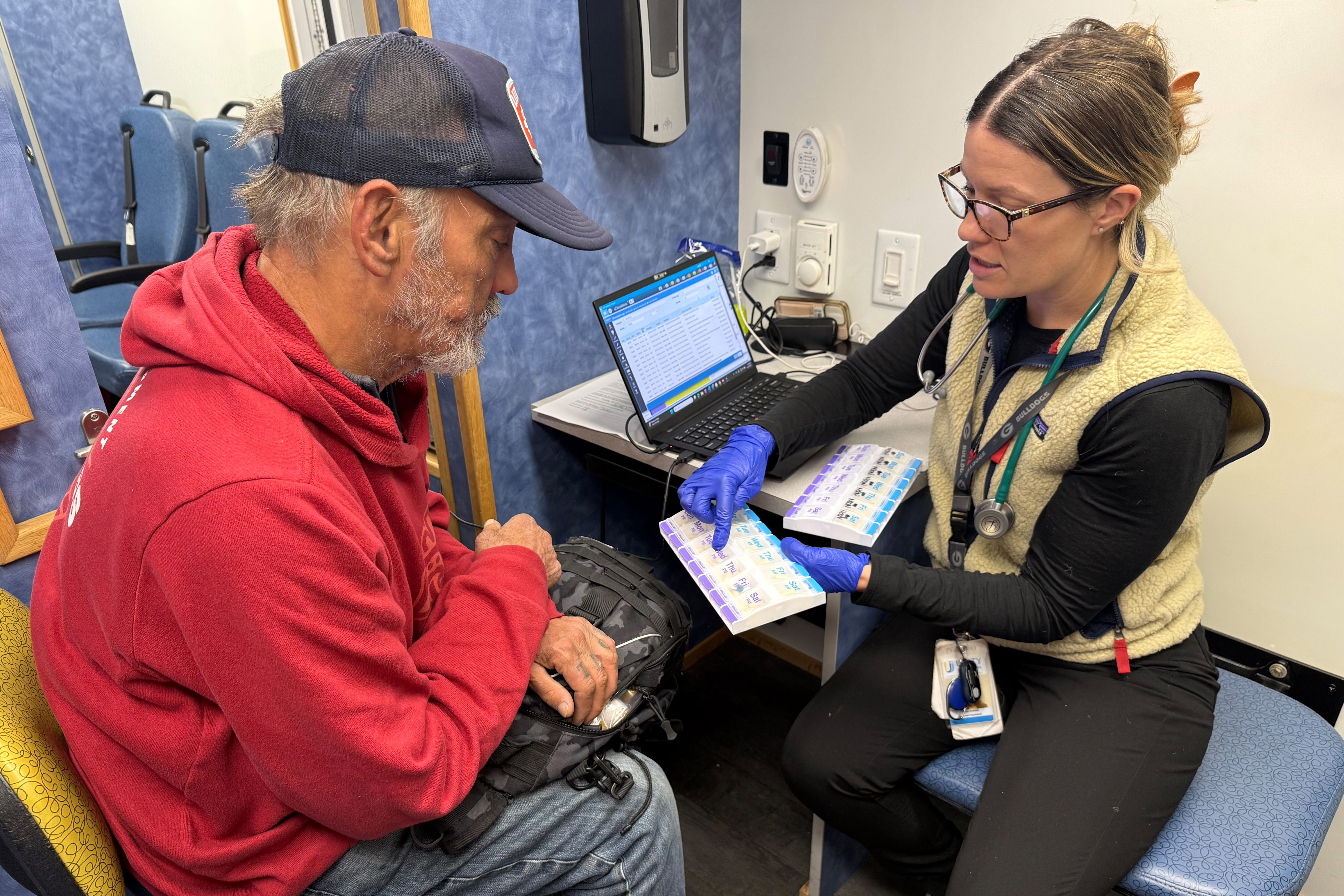

“I’m not seeing my patients for a month or more, and then when I do, their chronic conditions are uncontrolled. They’ve been in and out of the ER, and they’re more likely to be hospitalized,” said Anna Graham, a street medicine nurse practitioner for Unity Health Care, a network of clinics in Washington. “It’s just setting us back.”

Graham’s team stations its mobile medical van outside Miriam’s Kitchen at dinnertime to better find patients.

Willie Taylor, 63, was figuring out where to sleep for the night after grabbing dinner from Miriam’s. He saw Graham to receive his medications for advanced lung disease, seizures, chronic pain, and other health disorders.

He has difficulty walking and needs a wheelchair, which is complicated because he doesn’t have a permanent address. Taylor and his medical providers say his previous wheelchairs have been stolen while he slept outdoors at night. He uses a shopping cart to keep him steady, walking around all day, until nightfall.

On a cold November night, Graham helped Taylor figure out his daily medications and checked his vitals. The team handed him a warm coat and hand warmers before sending him back outside.

After walking for about 45 minutes, he found a piece of park pavement where he could build a bed out of tarps and sleeping bags.

“My body can’t take this,” Taylor said, preparing to sleep. “There’s ice on the concrete. I’m in so much pain; it hurts so much worse when it’s cold.”

Homeless people die younger and cost the health care system more than housed people, largely because conditions go untreated on the streets, and when they do seek care, many go to the ER. Among Medicaid enrollees, homeless people have been estimated to incur $18,764 a year in spending, compared with $7,561 for other enrollees.

Over at the So Others Might Eat soup kitchen earlier that day, Tyree Kelley was finishing his breakfast of a sausage sandwich and hard-boiled eggs. He was considering going into a shelter. The streets were becoming too dangerous for someone like him, he said, referring to the police and National Guard presence. He was feeling the loss of an encampment community that would watch his back.

He’s been to the ER at least seven times this year to get care for a broken ankle he sustained falling off an electric scooter. The accident caused him to lose his job and health insurance as a garbageman, he said. His situation has caused him to sink deeper into a depression that began three years ago after his mother died, he said.

Then his father and sister died this year. He began to numb his pain with beer.

“You get so depressed, being out here,” said Kelley, 42. “It gets addictive. You start to not care about even changing your clothes.”

His depression also led him to seek out marijuana. Then he smoked a joint laced with fentanyl. The overdose sent him to the hospital for days.

“I actually died and came back,” he said, crediting other homeless people with administering naloxone and saving his life. “I need to get out of this, but I feel so stuck.”

A few blocks west of the White House sits a vacant plot of land that earlier this year held more than a dozen tents. Workers in the area sense what they don’t always see.

“I was here when this was all cleared. A bulldozer came in, and all their stuff was thrown in a garbage truck,” said Ray Szemborski, who works across the street from the now-empty lot. “People are still homeless. I still see them around underneath the bridge. Sometimes they’re at bus stops, sometimes just walking around. Their tents are gone but they’re still here.”