California Gov. Jerry Brown signed landmark legislation Monday, allowing terminally ill patients to obtain lethal medication to end their lives.

In a deeply personal statement, Brown wrote that he read opposition materials carefully, but in the end was left to reflect on what he would want in the face of his own death.

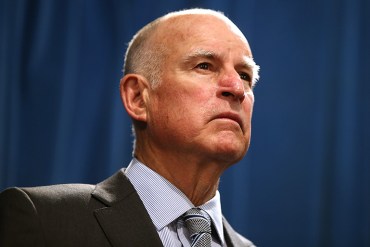

Calif. Gov. Jerry Brown (Photo by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

“I do not know what I would do if I were dying in prolonged and excruciating pain,” the former Jesuit seminarian wrote. “I am certain, however, that it would be a comfort to be able to consider the options afforded by this bill. And I wouldn’t deny that right to others.”

Brown, who is a Democrat, had been silent on the issue before Monday’s signing statement. If he had not signed the bill, it would have become law later this week.

The new law requires two different doctors to determine that a patient has six months or less to live before prescribing the drugs. The patient must voluntarily submit two oral requests at least 15 days apart, as well as a written request to the attending physician. And patients must be physically able to swallow the medication themselves, have the mental capacity to make medical decisions.

Brown’s signature concludes a hotly contested debate that elicited impassioned testimony from lawmakers, cancer patients who fear deaths marked by uncontrollable pain and suffering and religious and disability advocates who fear coercion and abuse.

The law will take effect in 2016, 91 days after the special legislative session concludes. At that time, California will become the fifth state to allow physician-assisted suicide. Oregon, Washington, Montana, and Vermont permit the practice. The practice was permitted in New Mexico until August, when an appeals court reversed a lower court ruling establishing physician-assisted suicide as a fundamental right. Advocates have appealed the case to the state Supreme Court, and a hearing is set for later this month.

The California law is set to expire in ten years, unless the Legislature passes another law to extend it.

Brown’s decision on the bill provoked strong reactions on Monday from proponents and opponents alike.

Disability rights advocates said depression and incorrect prognoses could lead seriously disabled people to end their lives prematurely.

“We’re disappointed,” said Deborah Doctor, legislative advocate for Disability Rights California. “We opposed the bill because of the lack of safeguards in it.”

Doctor said that Gov. Brown’s responsibility is to look at the impact of a bill on all of California, not just on himself. “If the standard should be that the people of California get what the governor gets, we would be looking at a very different system of health care, benefits, wages and housing.”

Doctor said the governor is ensuring that people have access to “physician-assisted suicide” before guaranteeing they have access to palliative care.

Tim Rosales, spokesman for Californians Against Assisted Suicide, said that this is “a dark day for Californians.”

“Governor Brown was clear in his statement that this was based on his experience and his background,” he said. “As someone of wealth and access to the best medical care and doctors, the governor’s background is very different than millions of Californians living in health care poverty.”

Rosales said those are the people who are potentially hurt by giving doctors the “power to prescribe lethal overdoses to patients.”

But California Sen. Dianne Feinstein, a Democrat, said Brown made the “absolutely correct” decision.

“I’ve seen firsthand the agony that accompanies prolonged illness, for both patients and loved ones, and this bill provides a compassionate, kind option,” Feinstein said in a prepared statement, which emphasized the bills safeguards.

Robert Liner, a retired obstetrician who is in remission from lymphoma, said he was thrilled with the governor’s action, having fought for this change for many years.

“It has been a long road,” Liner said. “I’m really glad Gov. Brown stepped up to the plate and signed it.”

Liner, 71, is part of a lawsuit seeking doctors’ right to avoid liability for prescribing lethal medication to terminally ill patients. Liner said he doesn’t know what he will do when he reaches the time to make a decision about his own life.

“But I really think it is important to have an option,” he said. “I am delighted.”

Correction: This story has been updated to correct the status of right-to-die litigation in New Mexico.