Six years ago, Erin was a newly minted graduate of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, working three part-time jobs and adjusting to life as a non-student. She stopped in for a drink one night at a restaurant in Chicago’s Bucktown neighborhood, where she got into a conversation with a guy. The next thing she remembers clearly was awakening at home the next morning, aching, covered in bruises, with a swollen lip.

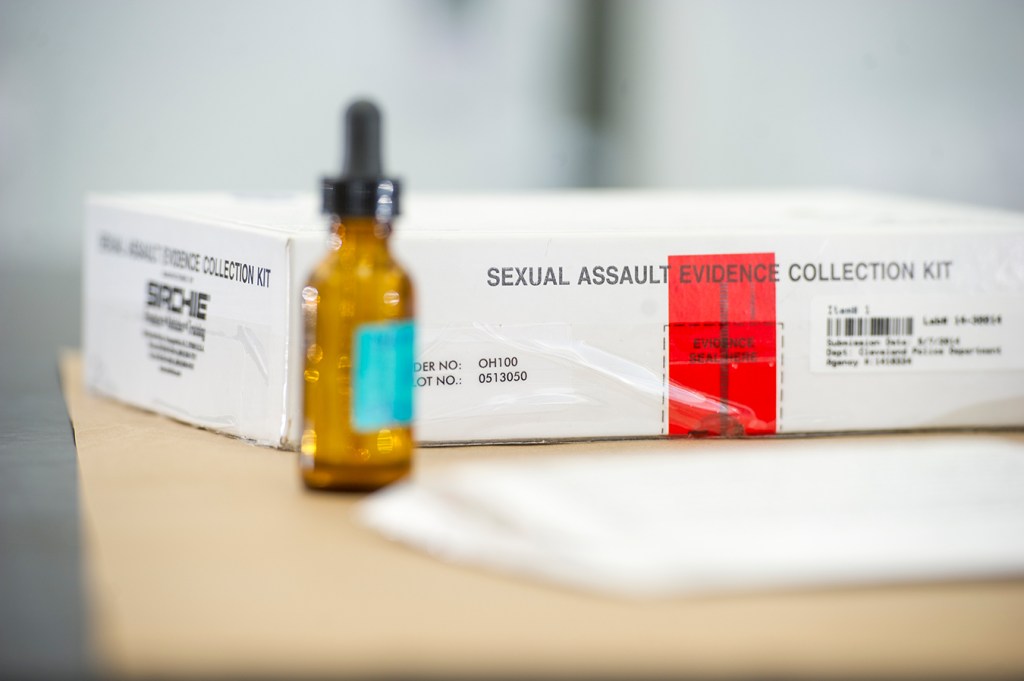

She believed she had been raped and went to the local police station to file a report. The police sent her to a hospital emergency room nearby, where a doctor did a medical forensic exam, checking her for injuries and taking evidence from her body and clothes to potentially use in a prosecution case. The exam took hours and made her even more miserable.

Police never made an arrest.

As time passed and Erin tried to move past the assault, she received regular, unwelcome reminders: bills from the hospital and emergency physicians group that treated her. The physicians group eventually sent her bill to a collection agency, and she started receiving nagging phone calls as well. Now 28 and living near Dallas, Erin still gets phone calls and letters a couple of times a year ordering her to pay up.

“When I get that phone call, it’s still so raw. I’m shaking,” Erin said. (Kaiser Health News does not use the full name of people reporting a rape if they request it be withheld.)

For 25 years, the federal Violence Against Women Act has required any state that wants to be eligible for certain federal grants to certify that the state covers the cost of medical forensic exams for people who have been sexually assaulted. Subsequent reauthorizations clarified that these individuals can’t be required to participate with law enforcement to get an exam, nor do they have to pay anything out-of-pocket for it, even if they would be reimbursed later.

Yet for some people who have been raped, the bills keep coming, despite this long-standing federal prohibition and laws in many states that provide additional financial protections.

“There’s often a disconnect between the emergency room personnel that take care of the person and the billing department that sends out the bills,” said Jennifer Pierce-Weeks, CEO of the International Association of Forensic Nurses, professionals who have specialized training in how to evaluate and care for victims of violent crime or abuse.

There is wide variation in how states meet their financial obligations to cover rape exams, sometimes called “rape kits,” that collect evidence of the crime. Many states tap funds they receive under the federal Victims of Crime Act. Others use money from law enforcement or prosecutors’ budgets or other designated options.

What services are covered as part of the rape exam can vary by state as well. Federal rules require that victims be interviewed and examined for physical trauma, penetration or force, and that evidence be collected and evaluated.

But many states include additional services without charging victims, including testing and treatment for pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases. Some may cover treatment for injuries that victims receive during the assault or for counseling.

Having financial protections for rape victims on the books, however, doesn’t necessarily translate to seamless, no-cost services on the ground.

For instance, New York requires that rape victims receive some services at no charge beyond the federal requirements, including emergency contraception and treatment for STDs, said Christopher Bromson, executive director of the Crime Victims Treatment Center in New York.

Still, last November the New York attorney general’s office announced settlements with seven hospitals that had illegally charged more than 200 rape patients for medical forensic exams, with amounts ranging from $46 to $3,000. In some cases, the hospitals referred the individuals to bill collectors who dunned them for the payments.

Afterward, the Healthcare Association of New York State, a nonprofit group that advocates for better health services, teamed up with the state Department of Health and others to present four webinars for hospital personnel to explain their legal responsibilities.

Karen Roach, the association’s senior director of regulatory affairs and rural health, said the billing problem in New York doesn’t appear widespread.

“Some of these issues arose from greater automation of the billing process,” she said. “Training is needed to flag these cases, to put systems in place not to automatically generate a bill.”

Working with an advocacy group, Erin eventually got the hospital to stop billing her. But the emergency physicians group no longer exists, and her $131.68 bill has been bundled with other debts and resold to different collectors several times, she said. She contacted Kaiser Health News and NPR through the “Bill of the Month” series, which explores exorbitant or baffling medical bills.

When she tells a debt collector that the bill they’re calling about is for services related to rape, “They say, ‘Oh, we’ll fix it,’ but they don’t,” Erin said. “They just sell it again and it just becomes someone else’s problem. But it’s always my problem.”

Despite state and federal laws, many people who were raped wind up paying for some medical services out-of-pocket, even if they have insurance. An analysis of billing records from 1,355 insured female rape victims found that in 2013 they paid an average $948 out-of-pocket for prescription drugs and hospital inpatient or outpatient services during the first 30 days after the assault. That amount represented 14% of total costs, the study found.

“We just assumed that this was only a problem for women who fell through the cracks,” said Kit Simpson, a professor in the department of health care leadership and management at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston, who co-authored the study. “But this was a systematic problem.”

Some rape victims don’t want to use their insurance in any case, because they are worried about privacy or safety issues if family members or others find out, advocates said.

The Violence Against Women Act, often referred to as VAWA, is up for reauthorization this year. It’s not clear if a new bill would address these payment issues.

If states don’t certify that they shoulder the cost of rape exams and don’t require victims to participate in the criminal justice system, their funds can be frozen. The Department of Justice declined to comment on enforcement of those VAWA provisions.

Some advocates would like to see the federal definition of what must be included in a no-cost medical forensic exam broadened to such services as testing and medication for pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections, including HIV. Such a move would level the playing field for rape victims across the country, they say.

Janine Zweig, associate vice president of justice policy at the Urban Institute, who co-authored a study examining state payment practices for rape exams, said a federal standard should be considered. “Do we really want it to be about which state you live in?”