House Republicans unveiled their much anticipated health law replacement plan Monday, slashing the law’s Medicaid expansion and scrapping the requirement that individuals purchase coverage or pay a fine. But they opted to continue providing tax credits to encourage consumers to purchase coverage, although they would configure the program much differently than the current law.

The legislation would keep the health law’s provisions allowing adult children to stay on their parents’ health insurance plan until age 26 and prohibiting insurers from charging people with preexisting medical conditions more for coverage as long as they don’t let their insurance lapse. If they do, insurers can charge a flat 30 percent late-enrollment surcharge on top of the base premium, under the Republican bill.

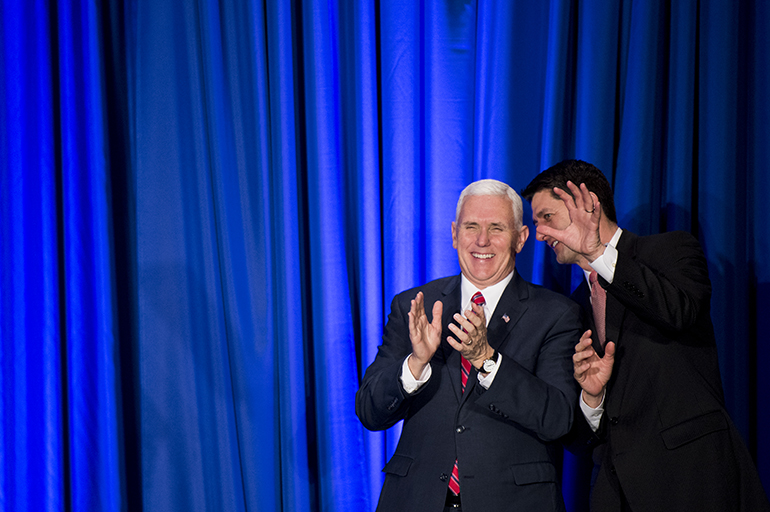

In a statement, House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) said the proposal would “drive down costs, encourage competition, and give every American access to quality, affordable health insurance. It protects young adults, patients with preexisting conditions, and provides a stable transition so that no one has the rug pulled out from under them.”

The GOP plan, as predicted, kills most of the law’s taxes and fees and would not enforce the so-called employer mandate, which requires certain employers to provide a set level of health coverage to workers or pay a penalty.

Democrats quickly condemned the bill. “Tonight, Republicans revealed a Make America Sick Again bill that hands billionaires a massive new tax break while shifting huge costs and burdens onto working families across American,” House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi tweeted. “Republicans will force tens of millions of families to pay more for worse coverage — and push millions of Americans off of health coverage entirely.”

The legislation has been the focus of intense negotiations among different factions of the Republican Party and the Trump administration since January. The Affordable Care Act passed in 2010 without a single Republican vote, and the party has strongly denounced it ever since, with the House voting more than 60 times to repeal Obamacare. But more than 20 million people have gained coverage under the law, and President Donald Trump and some congressional Republicans have said they don’t want anyone to lose their insurance.

When Republicans took control of both Congress and the White House this year, they did not have an agreement on the path for replacement, with some lawmakers from states that have expanded Medicaid concerned about the effect of repeal and the party’s conservative wing pushing hard to jettison the entire law.

Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.), one of those favoring a full repeal, tweeted: “Still have not seen an official version of the House Obamacare replacement bill, but from media reports this sure looks like Obamacare Lite!”

Complicating the effort is the fact that Republicans have only 52 seats in the Senate, so they cannot muster the 60 necessary to overcome a Democratic filibuster. That means they must use a complicated legislative strategy called budget reconciliation that allows them to repeal only parts of the ACA that affect federal spending.

Beginning in 2020, the GOP plan would provide tax credits to help people pay for health insurance based on household income and age, with a limit of $14,000 per family. Each member of the family would accumulate credits, ranging from $2,000 for an individual under 30 to $4,000 for people age 60 and older. The credits would begin to diminish after individuals reached an income of $75,000 — or $150,000 for joint filers.

Consumers also would be allowed to put more money into tax-free health savings accounts and would lift the $2,500 cap on flexible savings accounts beginning in 2018.

The legislation would allow insurers to charge older consumers as much as five times more for coverage than younger people. The health law currently permits a 3-to-1 ratio.

Community health centers would receive $422 million in additional funding in 2017 under the legislation, which also places a one-year freeze on funding for Planned Parenthood and prohibits the use of tax credits to purchase health insurance that covers abortion.

Both the Energy and Commerce and Ways and Means Committees are scheduled to mark up the legislation Wednesday. The committees do not yet have any Congressional Budget Office analysis of how much the legislation would cost or how many people it would cover.

Party leaders have said they want to have the bill to President Trump next month.

In a statement, senior Democrats on both panels said the measure would charge consumers “more money for less care. It would dramatically drive up health care costs for seniors. And repeal would ration care for more than 70 million Americans, including seniors in nursing homes, pregnant women and children living with disabilities by arbitrarily cutting and capping Medicaid,” said Rep. Frank Pallone of New Jersey and Rep. Richard Neal of Massachusetts.

The House GOP plan makes dramatic changes to Medicaid, the state-federal health insurance program that covers 70 million low-income Americans. The program began in 1965 as an entitlement — which means federal and state funding is ensured regardless of cost and enrollment. But the Republican bill would cap federal funding for Medicaid for the first time.

The federal government picks up between half and 70 percent of Medicaid costs. The percentage varies based on the relative wealth of the state.

Under the GOP plan, federal funding would be based on what the government spent in the fiscal year that ended Sept. 30. Those amounts would be adjusted annually based on a state’s enrollment and medical inflation.

Currently, federal payments to states also take into account how generous the state’s benefits are and what rate it uses to pay providers. That means states like New York and Vermont get higher funding than states like Nevada and New Hampshire and those differences would be locked in for future years.

Republicans have pushed to cap federal funding to states in return for giving them more control in running the program.

The legislation also affects the health law’s expansion of Medicaid, in which the federal government provided enhanced funding to states to widen eligibility. The bill would also end that extra funding for anyone enrolling under the expansion guidelines starting in 2020. But the legislation would let states keep the extra funding Obamacare provided for individuals already in the expansion program who stay enrolled.

About 11 million Americans have gained Medicaid coverage since 2014.

Changing the expansion program is a delicate balance for the Republicans. Four GOP senators from states that took that option said Monday they would oppose any legislation that repealed the expansion.

“We are concerned that any poorly implemented or poorly timed change in the current funding structure in Medicaid could result in a reduction in access to life-saving health care services,” Sens. Rob Portman of Ohio, Shelley Moore Capito of West Virginia, Cory Gardner of Colorado and Lisa Murkowski of Alaska wrote in a letter to Majority Leader Mitch McConnell.