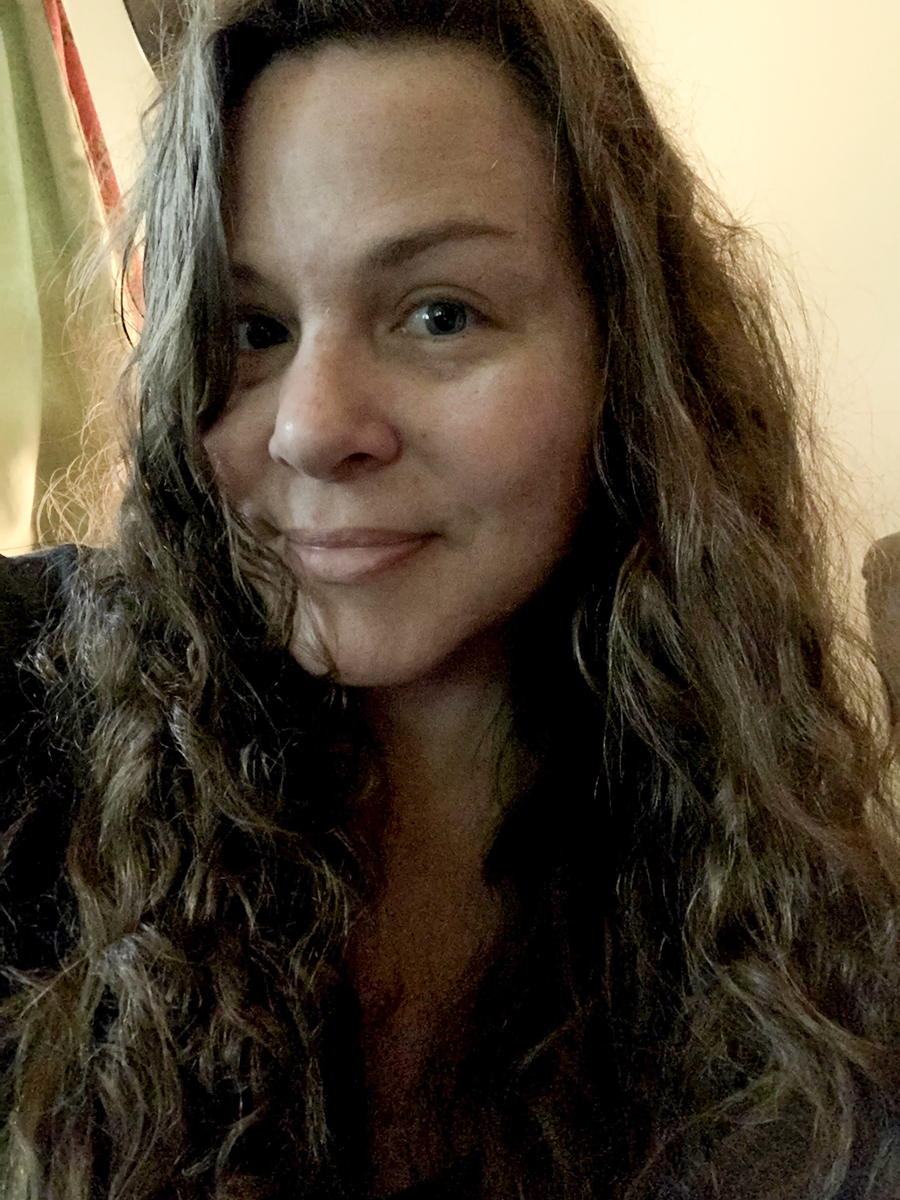

Kathleen Hambleton once used to spend $100 a week on Marlboro Reds.

The 43-year-old nurse from Saxtons River, Vt., paid a high price for her addiction to smoking, undergoing multiple throat surgeries. The financial hit was also a big burden.

After lozenges, patches and hypnosis failed to help Hambleton quit, she tried vaping. She is convinced she is healthier now and spends less than $40 per month on her vaping supplies.

But Vermont recently passed a 92% wholesale tax on vaping and e-cigarette products. Hambleton believes the sudden and sharp price hike is prohibitively expensive.

“When they imposed the 92% tax, I can’t affordably pay that,” she said. “No one can.”

Historically, taxation has been an effective tool in reducing the number of people who smoke.

The World Health Organization estimates that a 10% rise in prices causes overall smoking rates to drop about 4% in high-income countries. Some states are relying on this strategy to work again ― this time to discourage consumers, especially teenagers and young adults, from using e-cigarettes and vaping products.

Twenty states and the District of Columbia have passed those taxes, according to the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, a nonprofit advocacy group. But whether taxes would be as effective in combating vaping as they have been with smoking is unknown, state officials and researchers say.

Early studies suggest that hiking prices on vapers would have the same effect as on smokers.

“There are so many parallels here, and that’s why we’re taxing them like cigarettes,” said Richard Auxier, a researcher at the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center who specializes in state and local tax policy. “But [vaping] is new, and we should all just take a minute to know that it all might play out a little differently.”

The interest in taxes comes as states grapple with a marked increase in e-cigarette use among teens. Nearly 28% of high school students reported using e-cigarettes in 2019, the latest National Youth Tobacco Survey reported. More than 5 million youth reported using e-cigarettes that year.

At the same time, public health officials are investigating an outbreak in serious lung injuries associated with some vaping products.

Molly Moilanen, vice president for communications of ClearWay Minnesota, a nonprofit advocacy and research organization, said increasing the cost of tobacco products adds muscle to reduction strategies.

“We know from tobacco prevention that price is king when it comes to inspiring people to quit, and when it comes to preventing youth from ever starting,” said Moilanen.

At the federal level, Congress has introduced several bills that would establish a nationwide e-cigarette and vaping tax. None have become law.

One major vaping advocacy organization supports the fiscal move. Tony Abboud, executive director of the vaping lobbying group Vapor Technology Association, said that a federal tax could help deter young people from buying these products and give the Food and Drug Administration more resources “to better enforce the laws” that regulate them.

States impose the vaping product taxes in a variety of ways. Among the most common: Retailers pay the tax as a percentage of the product’s wholesale price or a set price for each milliliter of nicotine in the vaping liquid.

The available data shows promise. A 2014 study tracked e-cigarette sales in 52 major U.S. markets using store scanner data and found that a 10% price increase reduced sales of disposable cigarettes by about 12% and about 19% for reusable ones. A separate 2018 analysis estimated that higher prices were linked to a decline in how often middle and high school students vaped.

However, Frank Chaloupka, an economist and research professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago who co-authored these studies, acknowledged the data does not reflect some important aspects of the e-cigarette market, such as sales from online vendors or local vape shops. Many vapers purchase their products from these retailers.

The studies also did not capture Juul’s impact. The popular device hit the market in 2015, after the study concluded, and that brand of e-cigarette accounts for more than half of the market share.

Implementing the taxes can also be complicated. Many e-cigarette products do not go through the usual distribution chain, so assessing wholesale taxes doesn’t capture all product sales, Chaloupka said.

On the other hand, he added, a per-milliliter tax may create a market where products with little liquid but high levels of addictive nicotine may cost less than items with a greater volume but lower amounts of nicotine.

Kathleen Hambleton turned to vaping to help her stop smoking, but she says that the 92% tax Vermont is levying on vaping and e-cigarette products may be prohibitively expensive.(Courtesy of Kathleen Hambleton)

“In some ways, if you’re trying to … reduce the use of products like Juul that are popular among kids,” Chaloupka said, “that’s not going to do that.”

The products eligible for the charge also vary by state. Some areas tax only the nicotine, while others attempt to tax all e-liquids and devices. Pennsylvania revised its rules after a 2018 court decision that said separately packaged components like heating coils and batteries could not be taxed under the state’s tobacco law.

A bare-bones list of taxable products could undermine state efforts to stop vaping, Chaloupka said. However, including too many devices and e-liquids might make it difficult to enforce a tax, he suggested. And even if states do create a comprehensive list of products, devices on the market are constantly changing.

“It’s just very, very hard to define the devices and components that make the taxes easy to implement,” Chaloupka said.

Vermont’s tax is assessed on vaping devices, components specific to vaping and all e-liquids — regardless of whether they contain nicotine. Although prices can vary by retail outlets and area, the tax elevates the suggested retail price of a Juul device from about $35 to a little more than $67 in southeastern Vermont, according to the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. A pack of Juul menthol pods goes up from about $16 to $30.70, the group estimated.

The tax prompted Gaetano Putignano, owner of Hambleton’s preferred vape store, to shutter two shops and open his business in New Hampshire, which in 2020 will begin levying an 8% wholesale tax on e-liquids containing nicotine, and a 30-cent-per-milliliter tax on nicotine in closed vaping devices like Juul.

Putignano, 49, who is on the Rockingham, Vt., town board, said he supports age limits for vaping products and restricting the sales of vaping products to certain establishments. However, he added, Vermont’s high tax ultimately drives local businesses away and won’t reduce youth use.

“They say it was to protect the kids,” Putignano said. “It’s already illegal for kids.”

Collecting data on whether taxes reduce e-cigarette and vape use has not been easy since some states don’t report those taxes separate from general tobacco revenue, said Laura Oliven, the tobacco control manager at the Minnesota Department of Health.

“The truth is we really don’t know what the impact” is of the tax, Oliven said, since state officials have not yet evaluated its effect. However, absent the tax, she thinks youth e-cigarette use rates would have been much higher.

Even with the right information on taxes, Wendy Max, a professor of health economics at the University of California-San Francisco, said data often lags behind reality.

“For electronic cigarettes, it’s only in the last couple of years that surveys have started to ask about them,” Max said. “And if you ask a question, it may be two or three years before we have the data that allow us to address the question.”

But time is of the essence. As of Nov. 20, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has identified nearly 2,300 cases of vaping-related illness. Forty-seven people have died, and at least one patient underwent a double lung transplant.

More than 80% of patients surveyed reported using products containing THC, the psychoactive ingredient in marijuana. The CDC has identified vitamin E acetate, a potentially dangerous additive to vaping products, in 29 patient fluid samples.