NEW YORK — From the time C.J. Wise found out she was pregnant with her son Finn, she’d been seeing an obstetrician who practiced at NYU Langone Medical Center. She was excited to deliver at the hospital, considered one of the best places for mothers and babies in New York City. When Hurricane Sandy hit, and NYU was evacuated and then closed, Wise says she was “very, very upset.”

“There’s enough uncertainty about when in that five-week period you’re going to go into labor: Am I going to get to the hospital? Is the labor going to be long? How painful it will be?” she explains. “You don’t want to think about where it’s going to happen.”

With NYU closed, Wise’s doctor was given temporary privileges to deliver at Beth Israel Medical Center. Wise was nervous, but to her great surprise, she loved it. The nurses and staff went out of their way to accommodate her, and she says the delivery was “perfect.” Next time around, she says she’ll “probably go back to Beth Israel” if her doctor decides to stay there as well.

As of mid-January, most of NYU is up and running again, including the labor and delivery unit. But the question still looms whether NYU will lose some of the patients and even doctors who sought refuge at NYU’s biggest competitors after the storm. If that happens, the storm could end up having a long term impact on NYU’s valuable share of the fiercely competitive health care market in New York City.

Most of the 500 NYU doctors who left for other hospitals have since returned, according to Dr. Andrew Brotman, a senior vice president there. But more than a dozen have applied for permanent privileges at competitors Mount Sinai Hospital and Beth Israel, according to those hospitals, and there are probably more at other institutions. It’s not clear how many of those doctors would also keep their privileges at NYU.

Brotman says he’s not concerned about the shift, and he isn’t surprised by claims that other hospitals tried to recruit some of the NYU doctors working there after the storm. “It is a very competitive environment. People try to recruit from each other having nothing to do with a storm. It happens all the time,” he says.

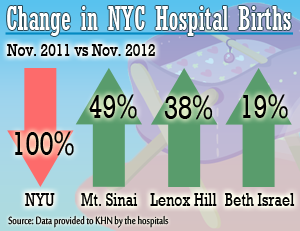

Brotman adds that while NYU was “extremely appreciative” of the warm welcome its staff received at other hospitals, NYU’s loss was in some ways its competitors’ gain. Hospitals like Lenox Hill, Mount Sinai and Beth Israel all saw spikes in their monthly birth rates during November and December, when NYU was closed.

NYU doctors were still able to bill insurers directly for their services, and some competitors – including Beth Israel – helped offset the salaries of doctors employed by NYU. But “doctor bills make up about 10-12 percent of the fee” for a test or procedure done at a hospital, explains Brotman. “The rest of it went to those other hospitals.”

Dr. Harris Nagler, the president of Beth Israel, says while they did not make any efforts to poach NYU doctors, Beth Israel did benefit from new doctors and patients being exposed to the hospital. He predicts that Beth Israel “will have a higher occupancy rate going forward. I think some patients and physicians will see the opportunity here and have enjoyed their experience and may seek new relationships.”

Accommodating the influx of patients — especially in the emergency department — was a real challenge for other hospitals, with a total of five New York institutions closed for at least some time after the storm. But they managed. The important question now isn’t whether hospitals return to pre-Sandy conditions, but whether they should, according to David Sandman, the senior vice president of the New York State Health Foundation. He was part of the so-called Berger Commission, a panel that was charged with rightsizing the state’s health care system six years ago.

“It was more than a wake-up call to remind us that New York City does have a lot of excess inpatient hospital capacity,” Sandman says. “When two very large hospitals — Bellevue with 900 beds and NYU which also has close to 900 beds — were suddenly taken out of service, we did have some backlogs and wait times at other places, but the system was able to absorb most of that capacity.” He hopes Sandy will lead to a renewed discussion about opportunities to downsize.

But NYU’s Brotman disagrees and argues that other hospitals struggled to meet the increased patient demand, particularly in labor and delivery. “It was really difficult to find places to deliver a baby in the city,” he says. “We have a renewed feeling that we’re needed and needed badly, and that makes everybody feel optimistic.”

Between damages and lost revenue, Brotman estimates that Sandy cost NYU $1.2 billion dollars. Funding from FEMA, the National Institutes of Health and NYU’s insurance policies should help them recover that in the next two to five years, Brotman says.

In the meantime, most of NYU’s units are back up and running, and the hospital’s census of patients is rebounding. It’s now about two-thirds of what it was before Sandy. Just a few days after the labor and delivery unit reopened, it was already bustling with doctors and nurses buzzing around the hallways.

Nurse Practitioner Donna Quinn says she enjoyed the month and a half she spent at Lenox Hill but always felt like a guest. “It makes you appreciate where you were, where your home is,” Quinn says.

Several of the doctors and nurses in the unit wore identical pins in the shape of the ruby slippers from The Wizard of Oz. NYU executives are hoping that the rest of the staff and patients will agree: There’s no place like home.