Haley Pollock carries a box of chalk in her car, ready for action.

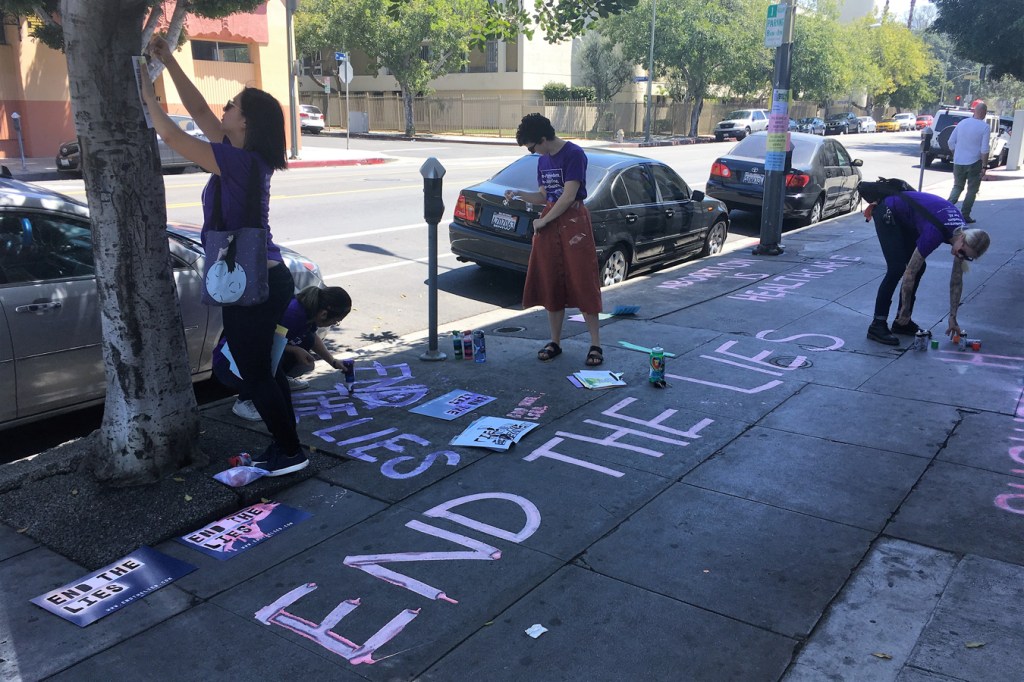

In her spare time, she and fellow community activists convert the sidewalks outside of crisis pregnancy centers into political canvases, scrawling phrases such as “Fake Women’s Clinic Ahead” and “End the Lies.”

Her team soon plans to carry out nighttime sorties — guerrilla-style — so people living near these centers find the pink, blue and yellow messages first thing in the morning.

“People are appalled when they learn about fake clinics,” said Pollock, 34, a student at Southwestern Law School in Los Angeles, who said her goal is to educate people.

Abortion-rights activists in California and beyond have launched or stepped up information campaigns in response to a June U.S. Supreme Court ruling that crisis pregnancy centers cannot be required to tell women about the availability of publicly funded family planning services, including contraception and abortion.

Through sidewalk drawings, bus-shelter ads and pop-up messages on mobile devices, these activists seek to spread the word themselves about such services, especially to young, low-income women. They aim to warn them about what they see as incomplete or false information provided by the centers, which are typically affiliated with Christian organizations and seek to persuade women to continue their pregnancies. Some of the centers are not licensed medical facilities.

The court ruling “inspires us to work harder, faster, more visibly than we were before,” Pollock said.

The court’s decision addressed a California law that went into effect in 2016, which had required the centers to post a notice informing women of state-funded health care options, including abortion and prenatal care. And if the centers were not medically licensed, or didn’t have licensed medical professionals on staff, they had to post a sign saying so. But the court ruled that the law, known as the Reproductive FACT Act, probably violates the centers’ free speech rights.

In an email to California Healthline, Anne O’Connor, vice president of legal affairs for the National Institute of Family and Life Advocates, lambasted the campaigns by abortion-rights activists as dishonest. Her organization filed the lawsuit taken up by the Supreme Court.

“There is nothing ‘fake’ about our medical professionals or our medical services,” she wrote. “Pro-abortion advocates will find that campaigns maligning pro-life pregnancy centers in this way are ineffective because they are not true.”

Nearly 1,200 of her group’s 1,450 member centers nationwide are licensed medical facilities staffed by doctors, nurses, nurse practitioners and physician assistants, O’Connor said. The remaining centers do not provide medical assistance, but rather counseling and social services, she said.

Of the 142 centers associated with the institute in California, about 100 are licensed medical clinics, O’Connor said. (Women who want to check whether a pregnancy center is a licensed clinic can search the state Department of Public Health’s “Cal Health Find Database.”)

Individual centers contacted directly for this article referred questions to O’Connor’s organization.

Borrowing from the playbook of anti-abortion activists who gather outside Planned Parenthood clinics, abortion-rights advocates are rallying regularly near crisis pregnancy centers, wielding signs and posting flyers. Pollock said they abide by existing laws and do not harass or block patients.

“At this point our only tool is information,” said Nourbese Flint, a program manager with the Los Angeles-based organization Black Women for Wellness. “We’re using ads to expose them and to let our communities know that these catfish clinics are out there.” (“Catfish” is a slang term that means deceptive or trying to pass as something it’s not.)

Her group is investing roughly $15,000 in ads, and eight went up at BART stations in the Bay Area last month, said Gabby Valle, a consultant leading the ad campaign in California.

The bright-pink posters show young black women next to messages such as “Catfished by a Clinic?” and “Stop Fake Clinics.” They also refer to a website that calls the pregnancy centers “F*@! Clinics” and “the Netflix and chill of clinics.”

Similar ads will appear on buses and bus shelters in south Los Angeles as early as this week.

Abortion-rights advocates charge that these centers are deceptive and trick women, especially young women of color, into coming into their offices by offering free diapers, pregnancy tests or ultrasounds — without offering a full-range of medical services. The activists say these clinics often set up shop in low-income communities, and near high schools and community colleges.

In New York City, an ordinance requires pregnancy centers to post a sign if they’re not licensed. Aviva Zadoff, director of advocacy at the National Council of Jewish Women in New York, said she and others fear the ordinance will be challenged given the California precedent.

The council leads what advocates call the “Pro-Truth” campaign, which has mapped out so-called fake clinics in New York City. Since the Supreme Court decision, the campaign plans to distribute brochures and flyers at community centers and colleges.

“We’ve learned that we can’t rely on laws and policies,” Zadoff said. “We as advocates have to work hard to educate each other and do what the law won’t do to protect women.”

Valle, of Black Women for Wellness, said the group has tried to create messages that resonate with women who use public transportation. The tricky part, she said, is describing a complicated matter in a small space. “We want to get the word out, but we don’t want to create fear of going to the doctor, because as it is, women of color are more likely to put off health care,” Valle said.

Black Women for Wellness is also sponsoring pop-up ads for mobile phone apps that link people to more information on these pregnancy centers. Valle estimates the mobile ads will reach approximately 250,000 people in San Bernardino, Riverside and Sacramento counties.

Meanwhile, chalk squads have hit the streets in Los Angeles, San Francisco and other cities.

After their work is done, the activists often remain near the pregnancy centers toting signs. Sometimes cars honk in support, Pollock said, or she’ll engage in fruitful conversations with locals.

“For the most part, neighbors are really receptive,” Pollock said, “but one time someone did call the police on us.”

KFF Health News' coverage of these topics is supported by California Health Care Foundation and The David and Lucile Packard Foundation

This story was produced by KFF Health News, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.