In the shadow of Silicon Valley, the hub of the world’s digital revolution, California officials still submit their records to the feds justifying billions in Medicaid spending the old-fashioned way: on paper.

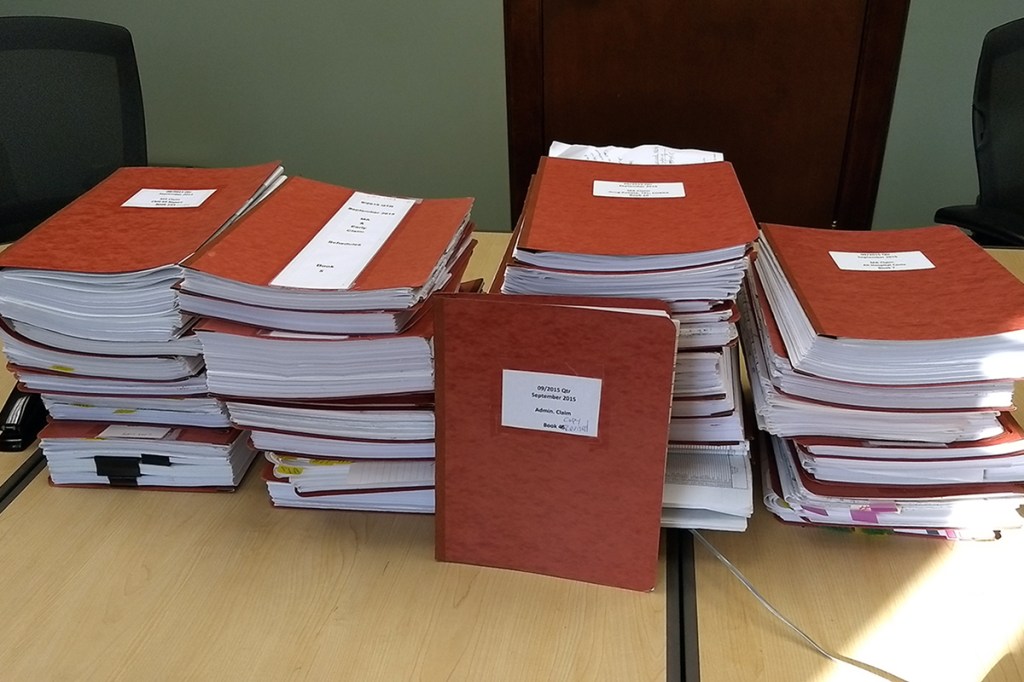

Stacks and stacks of it.

Stuck with decades-old technology, the nation’s largest Medicaid program forces federal officials to sift through thousands of documents by hand rather than sending electronic files. That’s one of the critical findings in a Sept. 5 report from the federal government’s chief watchdog citing inefficient and lax oversight of Medicaid nationwide.

To illustrate, the U.S. Government Accountability Office published a photo showing piles of records submitted for one three-month period. One folder was placed upright to show the height of the heap.

“It’s really amazing when you look at that picture,” said Carolyn Yocom, a health care director at the GAO who focuses on Medicaid, the federal-state health insurance program for low-income people. “For this type of reporting on expenditures, California really should be able to provide that electronically.”

California, with more than 13 million Medicaid enrollees, said it’s hamstrung because it uses 92 separate computer systems to run its Medicaid program — although it has plans underway to modernize its technology.

“Given system limitations and the magnitude of the supporting documentation, providing it electronically is currently not feasible,” the California Department of Health Care Services said in a statement.

The state’s Medicaid program, known as Medi-Cal, has struggled with technology for years. The state thought it had a solution in 2010 when it awarded a $1.7 billion contract to Xerox, which included $168 million for a new system. But after years of delay, the state scrapped the contract in 2016 and started from scratch, leaving the patchwork system in place a few more years.

Nationwide, despite industry buzz about electronic medical records, smartphone apps and artificial intelligence, a lot of paper is still being pushed across the health care system. Consider all those forms patients repeatedly fill out in the waiting room, the screeching sound of fax machines inside doctors’ offices and the bulging binders of patients’ records in file rooms.

Under Medicaid, states submit data quarterly to the federal government on their spending and include supporting documents such as invoices, cost reports and eligibility records. In California, reports on spending are shared electronically, but the copious supporting documentation required for federal review is not, according to the GAO.

When the Xerox venture failed, the company agreed to pay California more than $123 million as part of a settlement agreement, according to state officials.

Meantime, Conduent, the services unit of Xerox that was spun off into a separate company, was left to keep operating the system and process claims.

Last month, the state awarded a contract to DXC Technology of Tysons, Va., to take over some operations from Conduent. The state said the contract could be worth $698 million over 10 years.

Separately, California’s Medicaid officials are working on plans for a new system that would cost an estimated $500 million. Under the federal-state partnership on Medicaid, the federal government would cover 90 percent of those costs for design and implementation, and the state’s share would be about $50 million.

Pressure has been mounting on California to fix the situation. The Medicaid IT system “needs to be replaced, because it is more than 40 years old, its operations are inefficient, maintaining the system is difficult and there is a high risk of system failure,” state auditor Elaine Howle wrote in a June 26 letter to Gov. Jerry Brown and legislative leaders.

In her letter, Howle said the state was paying about $30 million annually to maintain the legacy system.

Overall, Medi-Cal serves 1 in 3 Californians. The annual Medicaid budget in California is about $104 billion, counting federal and state funds.

Beyond California, the GAO criticized the U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) more broadly. One complaint: Federal officials assign a similar number of staff to states for reviewing case files — even though some states, like California, pose a far bigger risk for enrollment errors and misspent money due to their size and complexity.

For instance, the report’s authors said, CMS reviewed claims for the same number of newly eligible Medicaid enrollees — 30 — in California as it did in Arkansas, even though California had 10 times the number of newly enrolled patients under the Affordable Care Act.

The report also said CMS devoted a similar number of staff to review both California, which represents 15 percent of federal Medicaid spending, and Arkansas, which accounts for 1 percent.

CMS “needs to step back and assess where are the biggest threats and vulnerabilities,” Yocom said. “If you aren’t looking, you don’t know what you aren’t catching.”

Overall, from fiscal years 2014 to 2018, federal Medicaid spending increased by about 31 percent, according to the GAO report. But the full-time staff at CMS dedicated to financial oversight declined by roughly 19 percent over the same period.

In a July 18 letter to the GAO, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services agreed with the agency’s recommendations for improving oversight efforts.

HHS wrote that it “will complete a comprehensive national review to assess the risk of Medicaid expenditures reported by states and allocate resources based on risk.”

This story was produced by KFF Health News, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.