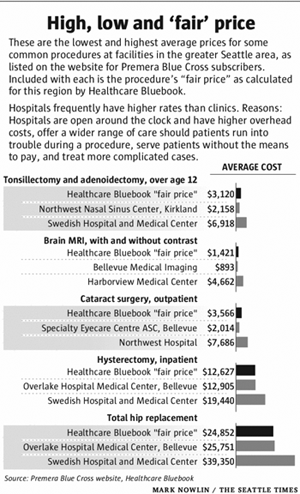

What if you had a headache that wouldn’t go away? At the area’s top trauma center, a brain MRI will cost more than $4,600, while an imaging center on the Eastside will charge $900.

Need your tonsils out? A Kirkland nasal-and-sinus clinic will charge you $2,200, but the surgery will be nearly $7,000 at a Seattle hospital. Which would you choose?

A prime objective of the Affordable Care Act is to bring down America’s health-care costs, which are the highest per person in the world. But how can the U.S. shrink its medical bills if patients are almost always buying health care with no idea what it costs?

Washington has been able to do little to shed light on health-care costs, and the state last year earned an “F ” for its cost-transparency laws, according to groups promoting health-care reform.

That soon could change.

Gov. Jay Inslee and some state lawmakers are pushing for new rules that would create a database listing hundreds of medical procedures, what they will cost at clinics and hospitals statewide, and information about the quality of the medical providers.

“We made a decision with the Affordable Care Act to use competition to control costs,” said Bob Crittenden, Inslee’s senior health-policy adviser. “Competition requires a number of things. You need enough information to make decisions, and we don’t have that right now.”

The proposal has backing from many big players in medicine and business, but the support is not universal. The state’s largest insurance companies — Regence Blue Shield and Premera Blue Cross — oppose requirements to share the treatment prices they’ve privately negotiated with clinics and hospitals.

There’s also the challenge of pairing cost data with information about the quality of a doctor or hospital. After all, who wants the cheapest physician if he’s also the worst?

And there are questions whether transparency can drive down prices. Hospitals and clinics have been consolidating, creating fewer, bigger companies and less competition. Lifesaving drugs and treatments might be available from only one company or location, giving patients little choice.

The biggest question is whether patients will seek this information and use it to shop more wisely. Transparency supporters think the public is ready for them to pull back the curtain on cost and quality.

“More information will beget more curiosity,” said Mary McWilliams, executive director of the Washington Health Alliance, a nonprofit that has earned national kudos for tracking the quality of health-care delivery.

“I think people have assumed it’s all the same quality and all the same cost,” she said. “Getting them to recognize that it’s not all the same is the first threshold.”

“Huge price variation”

When Jeff Rice was dinged $200 for cholesterol blood work that should have cost $20, the Tennessee-based physician turned his frustration into a business opportunity.

In 2008, Rice launched Healthcare Bluebook, a company that collects data on what insurance companies pay for medical care, then calculates a “fair price” for procedures from allergy tests to heart surgery. Consumers can search for prices for free online and use the information as a benchmark to shop around.

“Many patients don’t know there is this huge price variation,” Rice said.

There are other transparency tools available, but all have their limitations. Many insurance companies have online cost-comparison tools for their customers. A recent search on the Aetna site found prices for roughly 30 common procedures, while Regence lists prices for 350 services.

On the quality side, the Washington Health Alliance publishes “Community Checkup Report,” which evaluates the quality of doctors, clinics and hospitals. The national Leapfrog Group scores hospitals.

In coming months, lawmakers in Olympia will consider various proposals to expand and greatly improve such transparency. One bill would require insurance companies to enhance their shopping tools to include price and quality information side-by-side.

Recent hearing

A more controversial proposal would create an “All-Payer Claims Database.” Hospitals and clinics have a “billed” rate for services, but insurance companies negotiate lower “allowed” rates, the amount they agree to actually pay for a procedure. The legislation would require payers — mostly insurance companies — to reveal what they are spending on services at different locations, so the data could be compiled into a database available to everyone.

At a recent hearing for the bill, representatives from the Washington State Hospital Association, Washington State Medical Association, Seattle Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce and the National Federation of Independent Business all testified in support of creating the database.

Only Regence and Premera officials spoke against it.

The insurance companies carefully guard the rates they negotiate. They consider it proprietary information they are not keen to share with competitors, health-care providers and others.

“We simply do not believe that [the All-Payer Claims Database] has any history of demonstrating any meaningful cost or quality improvement,” said Premera’s Len Sorrin, at the hearing.

The companies do, however, support cost tools for their own customers. A spokesman for Regence testified that searching for prices drives patients to lower-cost options.

Databases in 11 states

So far, at least 11 states have created these databases in various forms, and many more are interested. Most of the databases were built in 2008 or later, and there’s little information on their effects on costs or quality.

But the world of health insurance is changing. Deductibles — the amount a patient must pay before an insurance company starts covering medical bills — are going up. More than one-third of insured workers have deductibles of $1,000 or more, and many plans also have “coinsurance,” which sets a percentage of medical bills patients must pay even if they’ve reached their deductible cap.

Gone are the days of visiting the doctor and paying a $15 copay. Patients are more frequently footing the bill.

“When it’s your money, you ask a lot more questions about what things cost,” said Rice, the founder of Bluebook.

But shopping for health care can be more complicated than buying other essentials.

Transparency supporters like to illustrate the influence of price by comparing it with buying gasoline. Most drivers check the posted per-gallon price before filling up. If one station offered gas at $4 a gallon, they would drive past the pump offering it for $20 a gallon — a degree of price difference seen in some medical services.

But is that the right metaphor? What if you’re driving on fumes and there’s no other pump for miles around? When you’re a desperate shopper, chances are you’ll pony up if you can.

Challenges, limitations

Some argue that by publishing the cost information, the cheaper locations will raise their prices rather than the expensive sites dropping theirs. Douglas Conrad, a professor in the University of Washington’s School of Public Health, called that argument a red herring. Over time, he said, the prices come down, whether through market forces or action by antitrust authorities.

The relationships patients develop with their doctors pose potentially more difficult complications.

Conrad acknowledges the challenges and limitations to how much influence transparency can exert on the health-care system, but he thinks it can make a positive difference.

“If price and quality information get out there, and there is a push by the state to force transparency where it’s been difficult to get … that could change things,” Conrad said. “The promise is there.”