Tens of thousands of uninsured residents in the poorest and most rural parts of Mississippi may be unable to get subsidies to buy health coverage when a new online marketplace opens this fall because private insurers are avoiding a wide swath of the state.

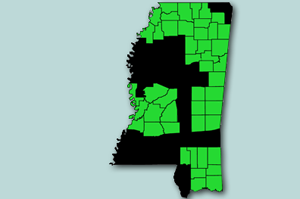

No insurer is offering to sell plans through the federal health law’s marketplaces in 36 of the state’s 82 counties, including some of the poorest parts of the Delta region, said Mississippi Insurance Commissioner Mike Chaney.

As a result, 54,000 people who may qualify for subsidized coverage would be unable to get it, estimates the Center for Mississippi Health Policy, a nonpartisan research group.

Many make a living picking soybeans, working on tree farms or in fast food restaurants, earning too little to buy coverage on their own.

“That’s the place where it’s most needed,” said Roy Mitchell, executive director of the Mississippi Health Advocacy Program. “There’s a high uninsured population there. One of the highest infant mortality rates in the country is in that area. A real lack of preventive care.”

One of the goals of the health law was to provide coverage to people who cannot afford coverage today. The gaps in Mississippi could undermine that promise for many residents of the Magnolia State.

There is still some time: The federal government has extended a deadline and allowed Mississippi to grant insurers several more weeks to file applications to sell coverage, Chaney said. The marketplaces open for enrollment Oct. 1, for individuals and small businesses.

Insurers declined to comment on the reasons they chose not to offer plans in those counties. But Chaney and others said concerns include the difficulty of creating networks of doctors and hospitals in rural areas, the poverty of the region and uncertainty about the health law.

Insurers “have a tendency not to want to come to a poor state and the poorest part of poor state,” said J. Stansel Harvey, CEO of Delta Regional Medical Center in Greenville, Miss.

Mississippi’s marketplace will be overseen by the federal government, following disagreement between Chaney and Republican Gov. Phil Bryant, who opposed Chaney’s plan to create a state-run online market.

Nationally, 17 states are running their own markets; the rest have defaulted to federal control.

Humana and Centene’s Magnolia Health Plan will offer coverage in more than half of the state’s counties when the marketplace opens, according to data from Chaney. But they aren’t offering plans in the other counties because they don’t have the needed networks of doctors and hospitals, Chaney said. He added that “uncertainty about the law” led BlueCross BlueShield of Mississippi, which currently sells in all parts of the state, not to seek approval for plans in the new marketplace.

“There’s a great concern about submitting plan to be approved on federal marketplace,” said Chaney.

Obama administration spokeswoman Joanne Peters declined to address the situation in Mississippi, but said the government “is working hard to create competitive marketplaces across the country.”

She did not answer questions about whether other states were facing similar problems.

Like hospital executives nationwide, Harvey was counting on expanded health coverage under the Affordable Care Act to cover many of the poor, uninsured patients who cost his 327-bed hospital millions each year in uncompensated care. Little or no relief is expected from increased Medicaid coverage, either, he noted, as a majority of state lawmakers appear opposed to expanding eligibility for that program under the health law.

“Where are these people going to get coverage?” asks Harvey.

Insurers currently sell policies in all 36 counties – and are expected to continue to do so next year – but only outside of the new marketplaces. Subsidies are available only through the marketplaces, so those sold outside of it come with no subsidy, and many residents are unlikely to purchase them without one.

“They are working in jobs that don’t provide them with health coverage, and their incomes are so low that they can’t afford to buy regular coverage,” said Margaret Gray, CEO of the Family Health Care Clinic, which serves 15,000 patients in the south and central parts of the state.