The paragraphs, buried deep in the 1,000-page House health reform bill, appear innocuous, but they have ignited a firestorm among critics predicting government-sponsored euthanasia.

The paragraphs, buried deep in the 1,000-page House health reform bill, appear innocuous, but they have ignited a firestorm among critics predicting government-sponsored euthanasia.

The controversy, over proposed Medicare funding of end-of-life counseling, has come to epitomize some of people’s deepest fears about the government’s role in health care.

Yet physicians who work with patients on end-of-life planning say that while they are surprised and upset about criticism of the proposal, it has brought needed attention to what they view as a long under-funded and overlooked service. Jon Radulovic, vice president for communications at the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, says the dispute “is providing the end-of-life care community with an opportunity to talk about what good care is and the services that are available.”

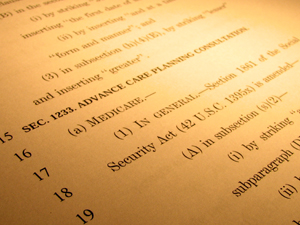

Section 1233 of the House bill would reimburse physicians for advance care planning consultations with any Medicare beneficiary, but it does not mandate the completion of any advance care directive or living will. The provision, advocates say, would pay for doctors to have those conversations while a patient is healthy and communicative rather than in the middle of a health crisis.

Much of the furor has centered on claims that the provision would give rise to ‘death panels’ and euthanasia, which experts have dismissed. But critics also have raised concerns about the vagueness and complexity of the language in the bill, asserting that it could be open to a wide interpretation and encourage government to play an excessive role in end-of-life issues.

Sen. Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa, the top Republican on the Finance Committee, vowed the panel would not include such a provision in its much anticipated health care reform package. “I don’t have any problem with things like living wills,” he said. “But they ought to be done within the family. We should not have a government program that determines if you’re going to pull the plug on grandma.”

Dr. Ted Epperly, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, often has advance end-of-life conversations in his work as a family physician and geriatrician in Boise, Idaho. He says the discussions can protect patients from having costly procedures done against their will.

Related Article

He describes such conversations as sensitive and time-consuming since they delve into the “nitty gritty” details: whether patients want to use ventilators to breathe, defibrillation to restart their hearts or feeding tubes for nourishment. He says the discussions are best done with a trusted physician who has developed a relationship with the patients. Family members are also sometimes involved, he says.

To start such a conversation, Dr. Diane E. Meier, an internist and director of the Center to Advance Palliative Care in New York City, says she asks her patients what they would want if they were hit by truck and in a coma or a situation where they were not expected to recover sufficiently to be aware of their surroundings. Some say they would want everything possible done to prolong life, But roughly nine out of 10 of her patients say they would want care to be focused on their comfort not sustaining life – if their brain was not functioning, according to Meier.

Dr. Gene Rudd, an ob-gyn and senior vice president of the Christian Medical & Dental Associations, said such conversations are part of good health care and should be encouraged. However, he worries that the provision could require that physicians use standardized language to counsel patients.

“It’s nothing novel here,” he said. “The novelty is the government then may be deciding that it can say what ought to be said in those sessions, not the fact that they ought to have these sessions and these discussions. It’s standard care.”

Still, health professionals say, these discussions are too rare. That’s largely because Medicare doesn’t explicitly pay for the service, discouraging doctors from taking the time to talk with patients about the issues. Private insurance companies often base their own payment policies on Medicare’s.

Currently, physicians generally classify the conversations under a funding code covering counseling and discussion of issues such as marital problems and depression associated with a job loss, Epperly says.

Medicare typically pays $92.33 for a 40 minute consultation, which Epperly says “drastically underpays for the complexity and the importance of this discussion,” adding that the creation of a new code – as called for in the House bill – would better value its importance.

Under the current payment system, Epperly notes, doctors could see five patients or complete a more lucrative procedure in the time it would take them to have an in-depth end-of-life consultation.

Meier, who also works as a professor of geriatrics and internal medicine at Mount Sinai School of Medicine, agrees: “It’s time consuming, it takes skills and it is so poorly paid that it is basically an act of charity … Physicians who are in a fee-for service environment legitimately cannot really afford to have” such conversations.”

“In my view, (the House bill) is a small and mostly symbolic effort to redress that imbalance of which physician services get paid for and which don’t,” she says.

In addition to the payment issues, doctors often don’t have such conversations because of time constraints and the sensitive nature of such talks. The shortage of primary care doctors has also contributed to the problem, experts say.

According to Epperly, as a result, only one out of five patients who should have such a consultation actually does.

Both opponents and proponents of the legislation acknowledge that it could produce significant savings. Studies show that 25 percent of the Medicare budget is spent on people during their final year of life with 40 percent of that spent in the final month.

Opponents worry that the cost savings might give doctors incentives to discourage treatment when they talk with their patients. The non-profit policy group Americans United for Life posted the following statement on its Web site: “The provisions that address end-of-life issues must be amended to leave no room for an interpretation that would pressure healthcare providers to make decisions based on cost rather than best medical care.”

Proponents say several studies show that having such conversations not only saves money but improves quality of care.

Researchers found patients with advanced cancer who had end-of-life care conversations with physicians had significantly lower health care costs in their final week of life while higher costs were associated with worse quality of care, according to a 2009 study published in the Archives of Internal Medicine.

In addition, hospice has been shown to improve quality of life and reduce costs during the end of life. Patients using hospice care save Medicare close to $2,400 per beneficiary, researchers from Duke University concluded in a 2007 study. Meanwhile, research has found that hospice patients lived an average of 29 days longer than similar patients who did not enroll in hospice, according to a 2007 study in the Journal of Pain and Symptom Management.

Congress has waded into this issue before. The Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003 established the Hospice Education Consult, which provides Medicare coverage for a one-time hospice consultation that examines end-of-life care.

However, in order for that consultation to qualify for payment, the patient must be diagnosed with a terminal illness and have a prognosis of six months or less to live. Also, the act did not create a unique funding code.