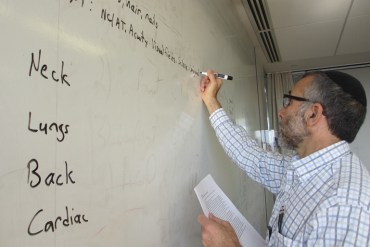

Dr. David Muller, a professor and dean at Mount Sinai Medical School, helps first-year students prepare to do physical exams on each other as part of a class called “The Art and Science of Medicine.” (Photo: Cindy Carpien for KHN)

NEW YORK — You can’t tell by looking which med students at Mount Sinai were traditional pre-meds in college and which weren’t. And that’s exactly the point.

Most of the class majored in biology or chemistry or some other “hard” science; crammed for the MCAT (the Medical College Admission Test) and did well at both.

But a growing percentage came through Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai’s “Hu-Med” program, which stands for Humanities in Medicine. They majored in things like English, history or medieval studies. And they didn’t even take the MCAT because Mount Sinai guaranteed them admission after their sophomore year of college.

Adding students to the mix who are educated in more than science is a serious philosophy at Mount Sinai.

David Muller is Mount Sinai’s Dean for Medical Education. One full wall of his cluttered office is a massive whiteboard almost totally full with to-do tasks and memorable quotes. One reads: “Science is the foundation of an excellent medical education, but a well-rounded humanist is best suited to make the most of that education.”

Mount Sinai Dean of Medical Education Dr. David Muller stands in front of a whiteboard in his office filled with notes along side memorable quotes. (Photo: Cindy Carpien for KHN)

The Hu-Med program dates back to 1987, when then-Dean Nathan Kase wanted to do something about what had become known as “pre-med syndrome.” That’s the idea that the drive for straight As and high test scores was actually producing sub-par doctors. Students were too single-minded.

Kase “really had a firm belief that you couldn’t be a good doctor and a well-rounded doctor and relate to patients and communicate with them unless you really had a good grounding in the liberal arts,” says Muller.

So the medical school began accepting humanities majors from a handful of top-flight liberal arts schools after their second year of college. They continue to follow their non-scientific interests for the remainder of their college careers.

Mount Sinai takes care of teaching them the science they need during the summers. It’s often not the science studied in pre-med programs.

The current required pre-med sciences – including basic chemistry, physics, and calculus – date from the early 1900s, when an educator named Abraham Flexner revolutionized medical school by turning it into a truly scientific endeavor.

But those core science courses haven’t changed much since Flexner, Muller says, while science has.

“The science for 1910 is only nominally relevant today; yet that’s the filter through which everyone has to come,” he said.

And it often weeds out people who could make excellent practitioners. Too frequently, he says, “if you can’t get an A minus in organic chemistry, you’re not going to be a doctor.”

Such artificial barriers “exclude people from medical school that we desperately need,” he says.

Studies have shown that the Humanities in Medicine students are just as successful in med school as any other student. And they are slightly more likely to choose primary care or psychiatry as a specialty – both areas where more physicians are needed.

At a recent end-of-year party thrown by the students for professors and administrators, even the teachers had trouble remembering who was a “Hu-Med” and who wasn’t.

Mount Sinai medical students in New York wait for free food to celebrate the end of the academic year. Even their teachers sometimes can’t remember which students came from traditional “pre-med” backgrounds and which pursued humanities as part of the school’s novel program. (Photo: Cindy Carpien for KHN)

Take Virginia Flatow, for instance. She’s a second-year student from New York. She majored in psychology at Bates College in Maine. Because she was also on the debate team, which meant lots of traveling to tournaments, she says she never would have been able to follow the classical pre-med track.

“There are very few courses – maybe I can think of one off the top of my head – where doing a lot of science in college helps you,” she says. “The rest of it is just a matter of how well do you study.”

Flatow agrees with a growing number of medical educators, for example, that organic chemistry is irrelevant for medical school. And that its difficulty discourages many students.

“I know so many people who took one semester of organic chemistry [and] dropped pre-med,” she said. “My brother was one of them.”

John Rhee, another second-year Hu-Med student, majored in public policy at Cornell. He was thinking about going into hotel management, but he decided to become a doctor after taking a summer job at a hospice.

“The experience was so deep for me,” he said, “partnering with a patient through end-of-life care.”

Keith Love (l) and Jimmy Murphy are first-year “Hu-Med” students at Mount Sinai. Neither majored in a “hard” science like biology or physics, nor did they have to take the dreaded medical school admission test. (Photo: Cindy Carpien for KHN)

Keith Love, a first-year Hu-Med from Colby College in Maine, said he originally gave himself a “zero percent chance” of going to medical school. He studied environmental science and anthropology in college, and still escapes Manhattan some early mornings to go birding. But, eventually, as he thought about how he wanted to make a difference with his career, he realized, “it was medicine.”

These non-traditional students also serve another role – they round out what could otherwise be a class full of science wonks.

“I think the cross-fertilization of ideas that goes [on] … ultimately, everyone benefits from it,” said Harsh Chawla, a third-year student from Danville, Calif. He did the traditional pre-med program, majoring in biology at the University of Southern California.

The effort has worked so well, in fact, that Mount Sinai is expanding it, opening it to students in any major from any college or university. Eventually half the class will be admitted from a slightly reconfigured program, which goes by the new name “Flex-med.”

Back in his office, Muller shows visitors his commanding view of the East River and East Harlem, “which is sort of the core community we serve as a medical school.”

Mount Sinai Dean of Medical Education David Muller gives a group of first year students a list of things to check during the physicals they are about to do on each other. (Photo: Cindy Carpien for KHN)

And while he describes his own pre-med training as “cookie cutter,” Muller has done his own share of thinking out of the box. Among other things, he is nationally recognized for helping create the largest academic home-visiting program for patients in the nation.

But what would he have pursued in college had he not headed straight onto the science track?

He thinks for a moment. “Literature, English lit,” he says in a wistful kind of way. “I read voraciously as a kid and that almost came to a complete standstill in college because there was just no time to breathe.”

And can pursuing different interests really make a better doctor? Of that Muller is confident.

“People who look at the same problems through different lenses will make us better in the long run,” he says. “Now, can I prove that’s going to be the case? No, but I’d like to believe that it is.”

This story is part of a reporting partnership between NPR and Kaiser Health News.