The end of nationwide abortion protections has been met with a wave of calls from lawmakers and governors in at least a dozen states for special legislative sessions that would reshape the state-by-state patchwork of laws that now govern abortion in the U.S.

“I haven’t seen so many states focusing their attention so quickly on one issue,” said Thad Kousser, a professor who studies state politics.

Peverill Squire, a professor who specializes in legislative bodies, agreed. “The number of special sessions likely to be held this year directly in response to Dobbs is out of the ordinary,” he said, referring to the June decision in which the Supreme Court struck down its 1973 ruling in Roe v. Wade.

But Kousser, Squire, and Mary Ziegler, a legal historian, said the rush to convene lawmakers during what otherwise would be legislative downtime was predictable.

After the Supreme Court granted states unfettered power to regulate abortion, the experts said, many want to address old laws, clarify conflicting laws, and create or extend enforcement mechanisms. And, Ziegler said, calls to restrict or expand abortion rights can be politically expedient for lawmakers, especially in deeply conservative states.

Kousser, a political science professor at the University of California-San Diego, said the coming lawmaking binge, triggered by the court’s ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson’s Women Health Organization, is unusual, even when compared with hot-button Supreme Court cases from the past. “Almost all of the Supreme Court rulings on social issues have taken power away from the states, and so there was no reason for states to call a special session after Obergefell v. Hodges because they lost their discretion, or after Griswold v. Connecticut,” Kousser said, referring to the decisions that legalized same-sex marriage and contraception use nationwide.

But in Dobbs, the court overturned the constitutional right to abortion nationwide and in doing so gave states more authority over the practice.

Squire, a political science professor at the University of Missouri, said state legislatures have a practical reason for responding to the Dobbs decision with special sessions. “Given that most controversial U.S. Supreme Court cases are handed down at the end of their term, in May or June, at a time when many state legislatures are no longer in regular session, having to call special sessions to address the court’s decision is not surprising,” he said.

Ziegler is a law professor at the University of California-Davis and studies the history of abortion. She said state lawmakers who want to further restrict abortion face tricky legal questions, such as whether they can prevent people from traveling to other states for abortions or from receiving abortion medications in the mail.

“How is anybody going to stop that from happening?” she said.

The special sessions are “a product of our contemporary politics of abortion,” Ziegler said, and differ from the reaction 49 years ago when the Supreme Court decided Roe v. Wade. “There were definitely some special sessions that happened not long after Roe to restrict access to abortion in limited ways, but abortion wasn’t the political hot-button issue then that it is now.”

Ziegler said many calls for special legislative sessions are occurring in “politically uncompetitive states” where Republican majorities are in control. “I think in some instances, even if polling would suggest that people in those states don’t want more abortion restrictions, Republicans don’t really have to worry about that because they’re not really worried about general elections,” she said. “So there’s probably, from their standpoint, no downside to doing this.”

Backing anti-abortion laws during special sessions could be politically advantageous for lawmakers, Ziegler said, especially in Republican primary elections.

Just a handful of states have full-time legislatures. In 14 states, only the governor may call a special session; in 36, either the governor or lawmakers can.

Governors and politicians in at least a dozen states responded to the Dobbs ruling with calls for special sessions. Most were in conservative states seeking to limit abortion access; lawmakers in a few liberal states want to protect abortion rights.

Lawmakers in Indiana, South Carolina, West Virginia, and South Dakota are planning sessions to ban or further restrict abortion.

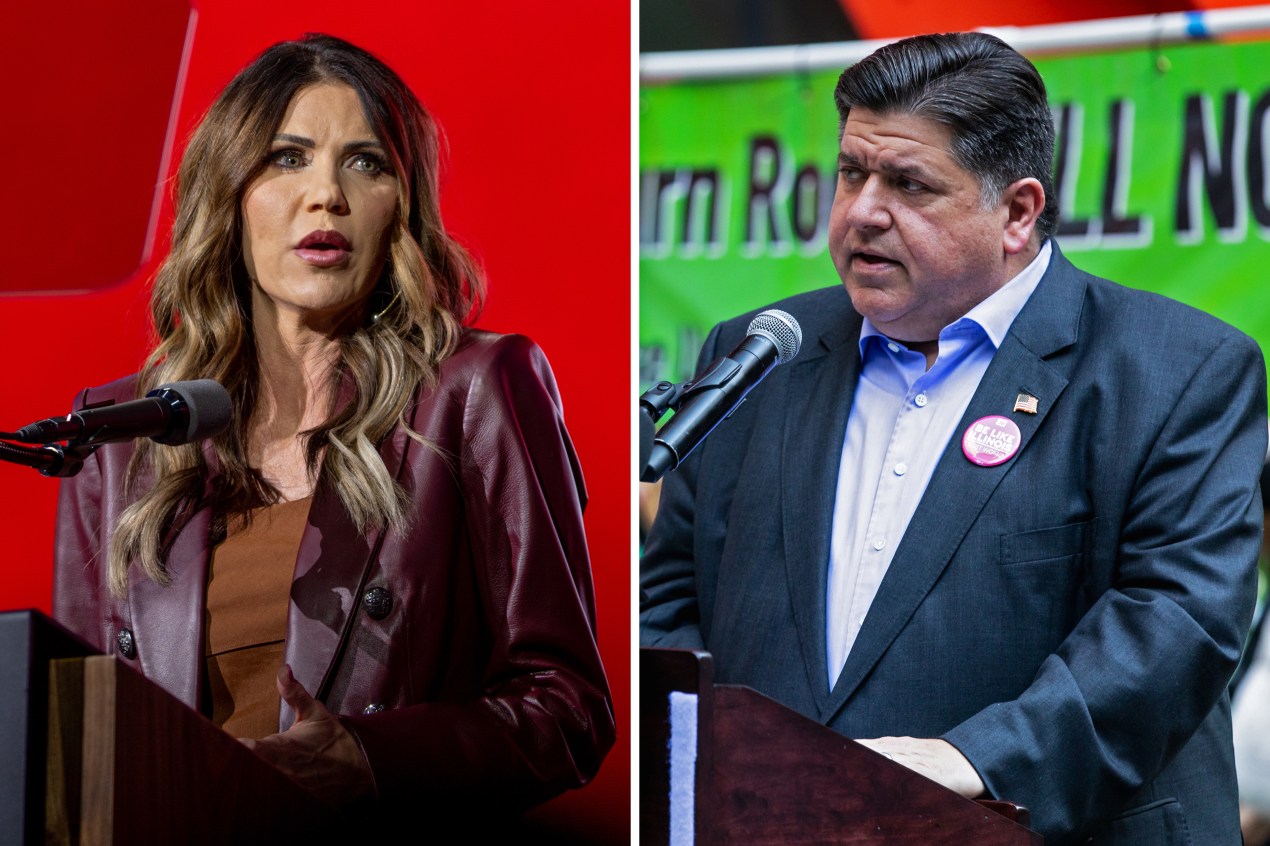

In South Dakota, Gov. Kristi Noem and legislative leaders announced they will convene a special session even though abortion was immediately banned there after the Dobbs decision by the state’s “trigger law.” Republican Jon Hansen, speaker pro tempore of the state’s House of Representatives, pledged to seek a litany of additional abortion restrictions.

In a May Twitter thread, Hansen outlined a half-dozen moves the legislature may consider, including criminalizing the use and shipment of abortion medications, prohibiting the advertisement of abortion services in the state, banning companies from paying travel costs for employees seeking abortions, and requiring out-of-state doctors to refer South Dakota abortion patients to third-party counseling before seeing them.

Leaders in multiple other states where abortion has been restricted have discussed, but not committed to, holding a special session. At least two Republican governors who have professed affinity for further restricting abortion have prioritized abortion-related litigation, instead of special sessions.

Other states have recently taken steps to expand abortion rights or plan to do so during special sessions.

At least nine states recently codified abortion rights or expanded access and protections. Gov. JB Pritzker in Illinois has called for a special session of the legislature to strengthen his state’s laws. Pritzker, a Democrat, pledged that Illinois would also prepare for an influx of people seeking abortions from states that now have bans.

And on July 1, New York lawmakers advanced legislation to give voters a chance to install protections for abortion and contraception in the state constitution.

Less pronounced in the rush to commence post-Roe lawmaking are calls to expand assistance for women who no longer have access to abortions. In South Dakota, the statement released by Noem’s office that calls for a special session mentions “helping mothers impacted by the decision.” But Noem hasn’t released a list of what, if any, social programs she proposes to add or expand.

Reporting and academic studies show that many states with laws that restrict abortion have limited participation in government assistance programs and high rates of poor health, economic, and social indicators. For example, South Dakota, which has high rates and racial disparities in infant and maternal mortality, has not expanded Medicaid eligibility or postpartum coverage, does not require paid family leave, and does not offer universal prekindergarten. Abortion restrictions are also associated with higher maternal mortality rates, according to a 2021 study by Tulane University researchers.

Ziegler questioned whether states that claim an interest in banning abortion will also claim a governmental duty to support pregnant people, suggesting they will instead “outsource” that role.

Will there “be anything actually done to support women other than just telling them to go to religious charities and crisis pregnancy centers?” she asked.