Black Americans are receiving covid vaccinations at dramatically lower rates than white Americans in the first weeks of the chaotic rollout, according to a new KHN analysis.

About 3% of Americans have received at least one dose of a coronavirus vaccine so far. But in 16 states that have released data by race, white residents are being vaccinated at significantly higher rates than Black residents, according to the analysis — in many cases two to three times higher.

In the most dramatic case, 1.2% of white Pennsylvanians had been vaccinated as of Jan. 14, compared with 0.3% of Black Pennsylvanians.

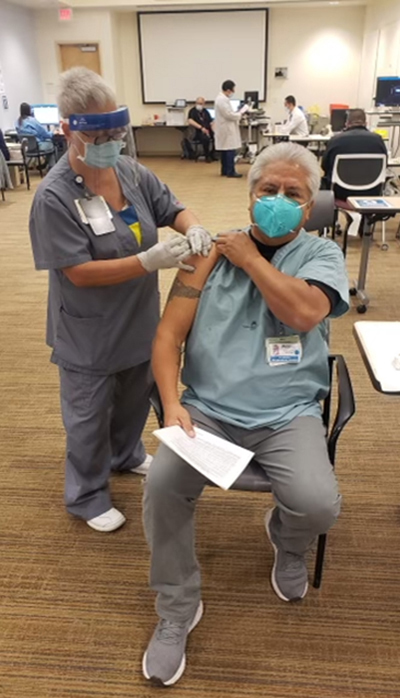

The vast majority of the initial round of vaccines has gone to health care workers and staffers on the front lines of the pandemic — a workforce that’s typically racially diverse made up of physicians, hospital cafeteria workers, nurses and janitorial staffers.

If the rollout were reaching people of all races equally, the shares of people vaccinated whose race is known should loosely align with the demographics of health care workers. But in every state, Black Americans were significantly underrepresented among people vaccinated so far.

Access issues and mistrust rooted in structural racism appear to be the major factors leaving Black health care workers behind in the quest to vaccinate the nation. The unbalanced uptake among what might seem like a relatively easy-to-vaccinate workforce doesn’t bode well for the rest of the country’s dispersed population.

Black, Hispanic and Native Americans are dying from covid at nearly three times the rate of white Americans, according to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention analysis. And non-Hispanic Black and Asian health care workers are more likely to contract covid and to die from it than white workers. (Hispanics can represent any race or combination of races.)

“My concern now is if we don’t vaccinate the population that’s highest-risk, we’re going to see even more disproportional deaths in Black and brown communities,” said Dr. Fola May, a UCLA physician and health equity researcher. “It breaks my heart.”

Dr. Taison Bell, a University of Virginia Health System physician who serves on its vaccination distribution committee, stressed that the hesitancy among some Blacks about getting vaccinated is not monolithic. Nurses he spoke with were concerned it could damage their fertility, while a Black co-worker asked him about the safety of the Moderna vaccine since it was the company’s first such product on the market. Some floated conspiracy theories, while other Black co-workers just wanted to talk to someone they trust like Bell, who is also Black.

But access issues persist, even in hospital systems. Bell was horrified to discover that members of environmental services — the janitorial staff — did not have access to hospital email. The vaccine registration information sent out to the hospital staff was not reaching them.

“That’s what structural racism looks like,” said Dr. Georges Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Association. “Those groups were seen and not heard — nobody thought about it.”

UVA Health spokesperson Eric Swenson said some of the janitorial crew were among the first to get vaccines and officials took additional steps to reach those not typically on email. He said more than 50% of the environmental services team has been vaccinated so far.

A Failure of Federal Response

As the public health commissioner of Columbus, Ohio, and a Black physician, Dr. Mysheika Roberts has a test for any new doctor she sees for care: She makes a point of not telling them she’s a physician. Then she sees if she’s talked down to or treated with dignity.

That’s the level of mistrust she says public health officials must overcome to vaccinate Black Americans — one that’s rooted in generations of mistreatment and the legacy of the infamous Tuskegee syphilis study and Henrietta Lacks’ experience.

A high-profile Black religious group, the Nation of Islam, for example, is urging its members via its website not to get vaccinated because of what Minister Louis Farrakhan calls the “treacherous history of experimentation.” The group, classified as a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center, is well known for spreading conspiracy theories.

Public health messaging has been slow to stop the spread of misinformation about the vaccine on social media. The choice of name for the vaccine development, “Operation Warp Speed,” didn’t help; it left many feeling this was all done too fast.

Benjamin noted that while the nonprofit Ad Council has raised over $37 million for a marketing blitz to encourage Americans to get vaccinated, a government ad campaign from the Health and Human Services Department never materialized after being decried as too political during an election year.

“We were late to start the planning process,” Benjamin said. “We should have started this in April and May.”

And experts are clear: It shouldn’t merely be ads of famous athletes or celebrities getting the shots.

“We have to dig deep, go the old-fashioned way with flyers, with neighbors talking to neighbors, with pastors talking to their church members,” Roberts said.

Speed vs. Equity

Mississippi state Health Officer Dr. Thomas Dobbs said that the shift announced Tuesday by the Trump administration to reward states that distribute vaccines quickly with more shots makes the rollout a “Darwinian process.”

Dobbs worries Black populations who may need more time for outreach will be left behind. Only 18% of those vaccinated in Mississippi so far are Black, in a state that’s 38% Black.

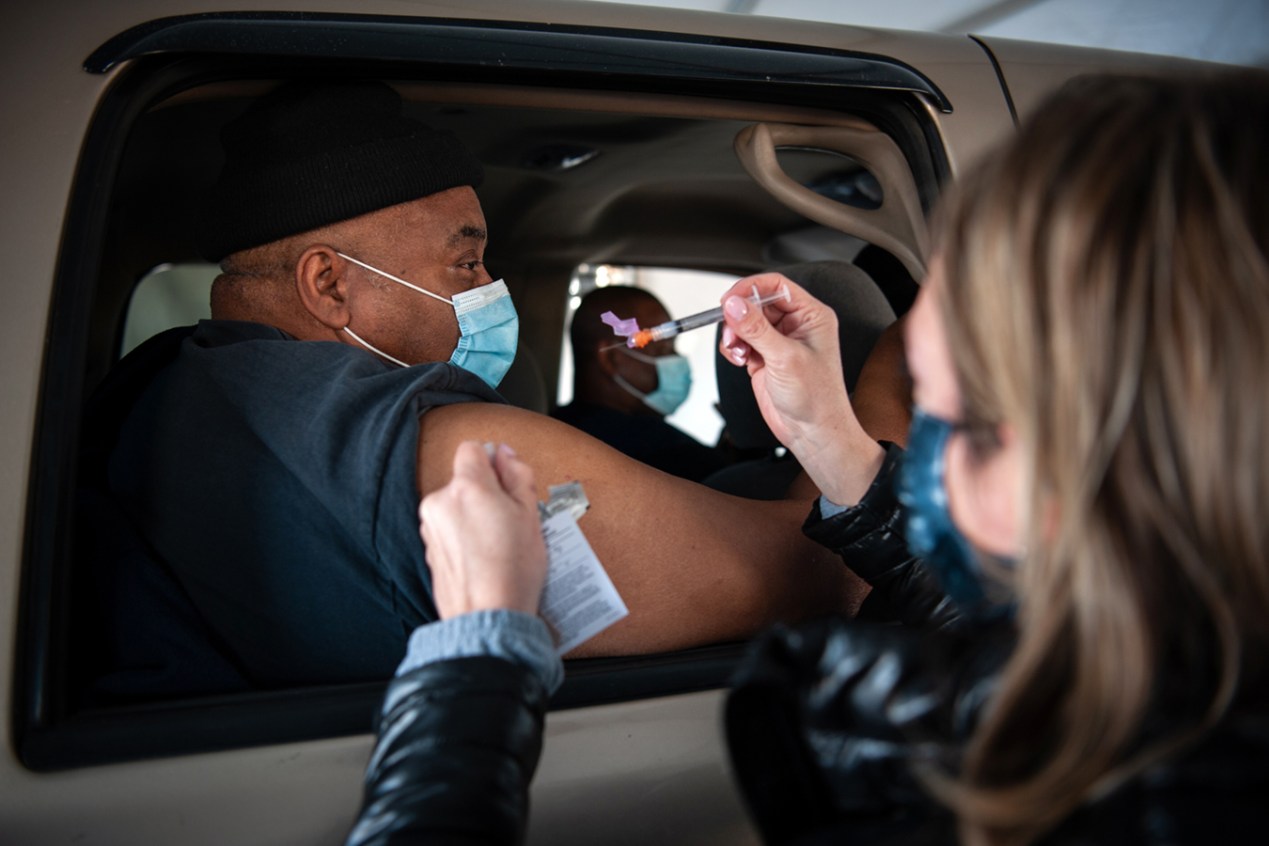

It might be faster to administer 100 vaccinations in a drive-thru location than in a rural clinic, but that doesn’t ensure equitable access, Dobbs said.

“Those with time, computer systems and transportation are going to get vaccines more than other folks — that’s just the reality of it,” Dobbs said.

In Washington, D.C, a digital divide is already evident, said Dr. Jessica Boyd, the chief medical officer of Unity Health Care, which runs several community health centers. After the city opened vaccine appointments to those 65 and older, slots were gone in a day. And Boyd’s staffers couldn’t get eligible patients into the system that fast. Most of those patients don’t have easy access to the internet or need technical assistance.

“If we’re going to solve the issues of inequity, we need to think differently,” Boyd said.

Dr. Marcus Plescia, chief medical officer at the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, said the limited supply of vaccine must also be considered.

“We are missing the boat on equity,” he said. “If we don’t step back and address that, it’s going to get worse.”

While Plescia is heartened by President-elect Joe Biden’s vow to administer 100 million doses in 100 days, he worries the Biden administration could fall into the same trap.

And the lack of public data makes it difficult to spot such racial inequities in real time. Fifteen states provided race data publicly, Missouri did so upon request, and eight other states declined or did not respond. Several do not report vaccination numbers separately for Native Americans and other groups, and some are missing race data for many of those vaccinated. The CDC plans to add race and ethnicity data to its public dashboard, but CDC spokesperson Kristen Nordlund said it could not give a timeline for when.

Historical Hesitation

One-third of Black adults in the U.S. said they don’t plan to get vaccinated, citing the newness of the vaccine and fears about safety as the top deterrents, according to a December poll from KFF. (KHN is an editorially independent program of KFF.) Half of them said they were concerned about getting covid from the vaccine itself, which is not possible.

Experts say this kind of misinformation is a growing problem. Inaccurate conspiracy theories that the vaccines contain government tracking chips have gained ground on social media.

Just over half of Black Americans who plan to get the vaccine said they’d wait to see how well it’s working in others before getting it themselves, compared with 36% of white Americans. That hesitation can even be found in the health care workforce.

“We shouldn’t make the assumption that just because someone works in health care that they somehow will have better information or better understanding,” Bell said.

In Colorado, Black workers at Centura Health were 44% less likely to get the vaccine than their white counterparts. Latino workers were 22% less likely. The hospital system of more than 21,000 workers is developing messaging campaigns to reduce the gap.

“To reach the people we really want to reach, we have to do things in a different way, we can’t just offer the vaccine,” said Dr. Ozzie Grenardo, a senior vice president and chief diversity and inclusion officer at Centura. “We have to go deeper and provide more depth to the resources and who is delivering the message.”

That takes time and personal connections. It takes people of all ethnicities within those communities, like Willy Nuyens.

Nuyens, who identifies as Hispanic, has worked for Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles Medical Center for 33 years. Working on the environmental services staff, he’s now cleaning covid patients’ rooms. (KHN is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.)

In Los Angeles County, 92% of health care workers and first responders who have died of covid were nonwhite. Nuyens has seen too many of his co-workers lose family to the disease. He jumped at the chance to get the vaccine but was surprised to hear only 20% of his 315-person department was doing the same.

So he went to work persuading his co-workers, reassuring them that the vaccine would protect them and their families, not kill them.

“I take two employees, encourage them and ask them to encourage another two each,” he said.

So far, uptake in his department has more than doubled to 45%. He hopes it will be over 70% soon.