The Maryland Proton Treatment Center chose “Survivor” as the theme for its grand opening in 2016, invoking the reality-TV show’s tropical sets with its own Tiki torches, palm trees and thatched booths piled with pineapples and bananas.

It was the perfect motif for a facility dedicated to fighting cancer. Jeff Probst, host of CBS’ “Survivor,” greeted guests via video from a Fiji beach.

But behind the scenes, the $200 million center’s own survival was less than certain. Insurers were hesitating to cover procedures at the Baltimore facility, affiliated with the University of Maryland Medical Center. The private investors who developed the machine had badly overestimated the number of patients it could attract. Bankers would soon be owed repayment of a $170 million loan.

Only two years after it opened, the center is enduring a painful restructuring with investors poised for huge losses. It has never made money, although it has ample cash to finance operations, said Jason Pappas, its acting CEO since November. Last year it lost more than $1 million, he said.

Volume projections were “north” of the current rate of about 85 patients per day, Pappas said. How far north? “Upper Canada,” he said.

For years, health systems rushed enthusiastically into expensive medical technologies such as proton beam centers, robotic surgery devices and laser scalpels — potential cash cows in the one economic sector that was reliably growing. Developers got easy financing to purchase the latest multimillion-dollar machine, confident of generous reimbursement.

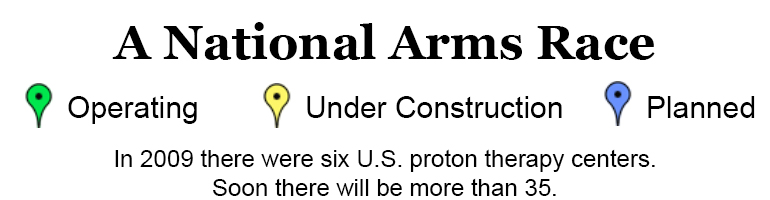

There are now 27 proton beam units in the U.S., up from about half a dozen a decade ago. More than 20 more are either under construction or in development.

But now that employers, insurers and government seem determined to curb growth in health care spending and to combat overcharges and wasteful procedures, such bets are less of a sure thing.

The problem is that the rollicking business of new medical machines often ignored or outpaced the science: Little research has shown that proton beam therapy reduces side effects or improves survival for common cancers compared with much cheaper, traditional treatment.

(Story continues below.)

If the dot-com bubble and the housing bubble marked previous decades, something of a medical-equipment bubble may be showing itself now. And proton beam machines could become the first casualty.

“The biggest problem these guys have is extra capacity. They don’t have enough patients to fill the rooms” at many proton centers, said Dr. Peter Johnstone, who was CEO of a proton facility at Indiana University before it closed in 2014 and has published research on the industry. At that operation, he said, “we began to see that simply having a proton center didn’t mean people would come.”

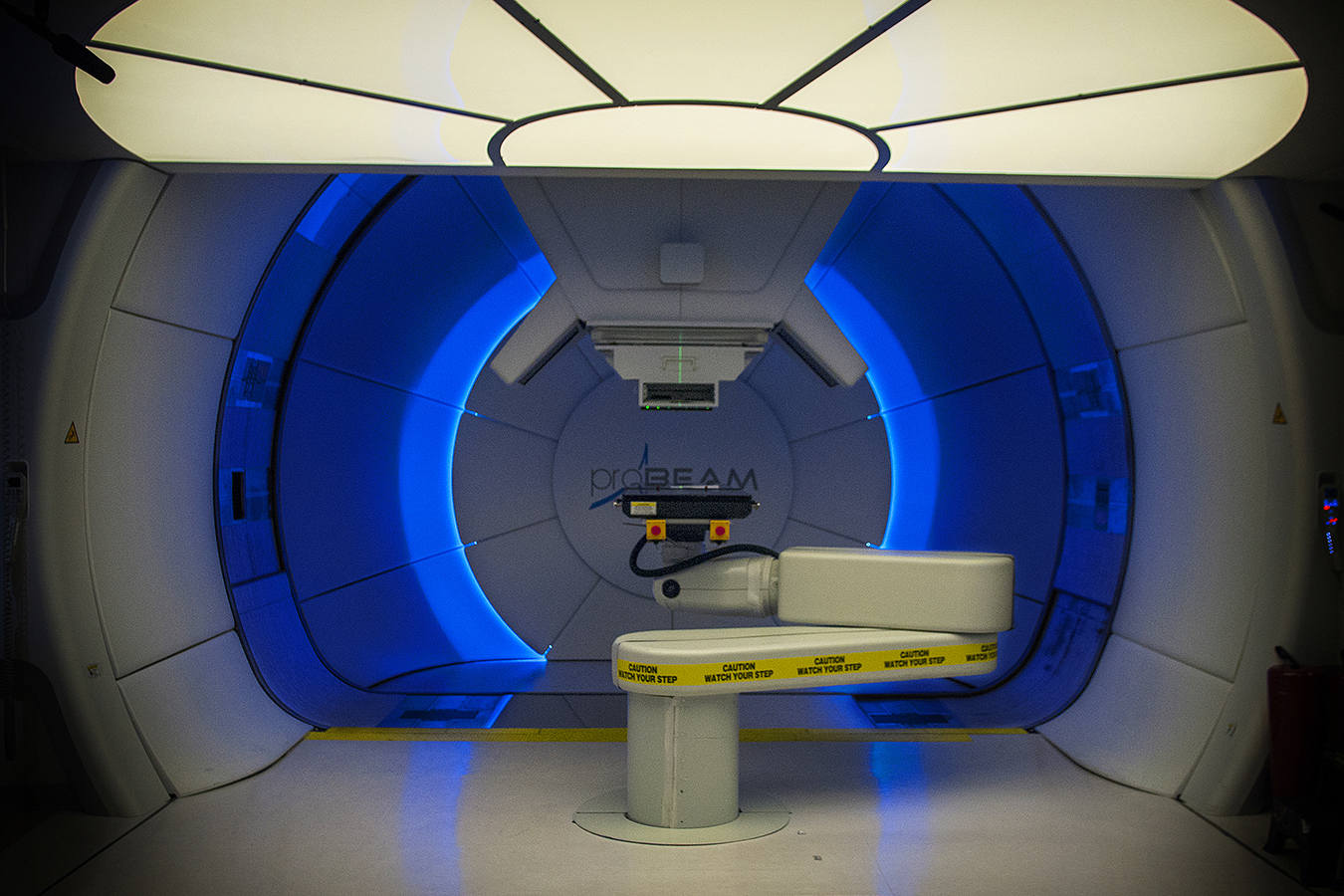

Sometimes occupying as much space as a Walmart store and costing enough money to build a dozen elementary schools, the facilities zap cancer with beams of subatomic proton particles instead of conventional radiation. The treatment, which can cost $48,000 or more, affects surrounding tissue less than traditional radiation does because its beams stop at a tumor rather than passing through. But evidence is sparse that this matters.

And so, except in cases of childhood cancer or tumors near sensitive organs such as eyes, commercial insurers have largely balked at paying for proton therapy.

“Something that gets you the same clinical outcomes at a higher price is called inefficient,” said Dr. Ezekiel Emanuel, a health policy professor at the University of Pennsylvania and a longtime critic of the proton-center boom. “If investors have tried to make money off the inefficiency, I don’t think we should be upset that they’re losing money on it.”

Investors backing a surge of new facilities starting in 2009 counted on insurers approving proton therapy not just for children, but also for common adult tumors, especially prostate cancer. In many cases, nonprofit health systems such as Maryland’s partnered with for-profit investors seeking high returns.

Companies marketed proton machines under the assumption that advertising, doctors and insurers would ensure steady business involving patients with a wide variety of cancers. But the dollars haven’t flowed in as expected.

Indiana University’s center became the first proton-therapy facility to close following the investment boom, in 2014. An abandoned proton project in Dallas is in bankruptcy court.

California Protons, formerly associated with Scripps Health in San Diego, landed in bankruptcy last year.

A number of others, including Maryland’s, have missed financial targets or are hemorrhaging money, according to industry analysts, financial documents and interviews with executives.

- The Hampton University Proton Therapy Institute in Virginia has lost money for at least five years in a row, recording an operating loss of $3 million in its most recent fiscal year, financial statements show.

- The Provision CARES Proton Therapy Center in Knoxville, Tenn., lost $1.7 million last year on revenue of $23 million — $5 million below its revenue target. The center is meeting its debt obligations, said Tom Welch, its president.

- Centers operated by privately held ProCure in Somerset, N.J., and Oklahoma City have defaulted on debt, according to Loop Capital, an investment bank working on deals for new proton facilities.

- A facility associated with the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance, a consortium of hospitals, lost $19 million in fiscal 2015 before restructuring its debt, documents show. Patient volume is growing but executives “continue to be disappointed in the slower-than-expected acceptance of proton therapy treatment” by insurers, said Annika Andrews, CEO of SCCA Proton Therapy.

- A center near Chicago lost tens of millions of dollars before restructuring its finances in a 2013 sale to hospitals now affiliated with Northwestern Medicine, documents filed with state regulators show. The facility is “meeting our budget expectations,” said a Northwestern spokesman.

Representatives from ProCure and the facilities in San Diego and Hampton did not respond to repeated requests for interviews.

“In any industry that’s really an emerging industry, you often have people who enter the business with over-exuberant expectations,” said Scott Warwick, executive director of the National Association for Proton Therapy. “I think maybe that’s what went on with some of the centers. They thought the technology would grow faster than it has.”

In the absence of evidence showing protons produce better outcomes for prostate, lung or breast cancer, “commercial insurers are just not reimbursing” for these more common tumors, said Brandon Henry, a medical device analyst for RBC Capital Markets.

The most expensive type of traditional, cancer-fighting radiation — intensity modulated radiation therapy — costs around $20,000 per treatment, while others cost far less. The government’s Medicare program for seniors covers proton treatment more often than private insurers but is insufficient by itself to recoup the massive investment, analysts said.

The rebellion by private insurers “is very, very good” and may signal the health system “is finally figuring out how to say no to low-value procedures,” said Amitabh Chandra, a Harvard health policy professor who has called proton facilities unaffordable “Death Stars.”

Proton centers are fighting back, enlisting patients, legislators and nonprofits to push for reimbursement. Oklahoma has passed and Virginia has considered legislation to effectively require insurers to cover proton therapy in more cases.

An entire day at the 2017 National Proton Conference in Orlando was dedicated to tips on getting paid, including a session titled “Strategies for Engaging Health Insurance on Proton Therapy Coverage.”

Proton facilities tell patients the therapy is appropriate for many kinds of cancer, never mentioning the cost and guiding them through complicated appeals to reverse coverage denials. The Alliance for Proton Therapy Access, an industry group, has online software for generating letters to the editor demanding coverage.

In hopes of navigating a difficult market, many new centers are smaller — with one or two treatment rooms — and not as expensive as the previous generation of units, which typically have four or five rooms, like the Baltimore facility, and cost $200 million or more.

Location is also critical. Treatment requires near-daily visits for more than a month, which may explain why larger centers such as Maryland’s never attracted the out-of-town business they needed.

To make the finances work, hospitals are combining forces. The first proton beam center in New York City is under construction, a joint project of Memorial Sloan Kettering, Mount Sinai and Montefiore Health System.

Smaller facilities, which can cost less than $50 million, should be able to keep their rooms full in many major metro areas, said Prakash Ramani, a senior vice president at Loop Capital, which is helping develop such projects in Alabama, Florida and elsewhere.

Maryland’s center hopes to break even by year’s end, executives said. That will involve refinancing, converting to nonprofit, inflicting losses on investors and issuing municipal bonds.

But plans call for four centers soon to be open in the D.C. area.

“It’s a real arms race,” said Johnstone, the former proton-center CEO, who has co-authored papers on proton-therapy economics. He is now vice chair of radiation oncology at Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, which doesn’t have a proton center. “What places need now are patients — a huge supply of patients.”