There’s a prescription drug abuse problem sweeping the United States, but fixing it will require a systematic change focused on how most health professionals prescribe drugs, rather than changing the practices of a few bad apples.

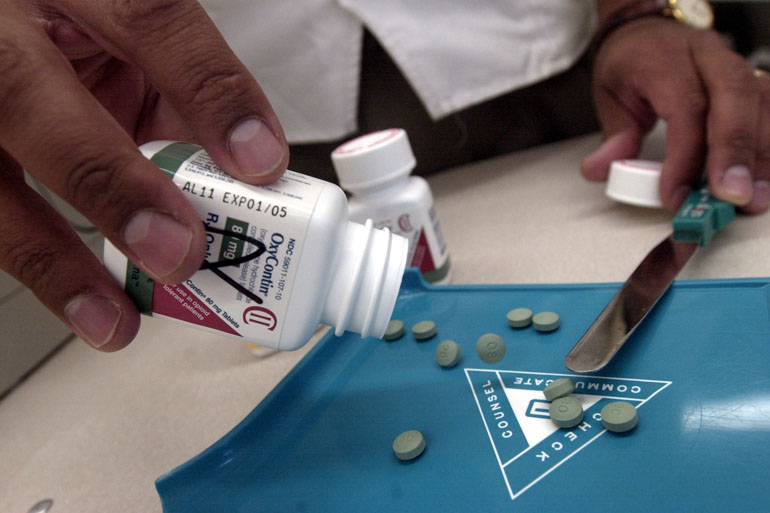

At least, that’s the recommendation put forth in a research letter published Monday in JAMA Internal Medicine. Researchers examined Medicare claims from 2013 to see which doctors prescribed opioids — a class of drug that includes OxyContin, morphine and codeine — and how many prescriptions they filled.

They found that the drugs are prescribed by a broad cross-section of medical professionals – including doctors, nurse practitioners, physicians’ assistants and dentists – rather than concentrated among a small group of practitioners. That means overprescribing opioids, they suggested, is a problem to which a majority of health professionals are contributing, not the work of a small minority.

“You need to address everyone, or at least a larger amount of prescribers than a few deviants,” said study author Dr. Jonathan Chen, who is also an instructor at the Stanford University School of Medicine. “If you want to come up with a solution, you need to take that into account, or nothing will be effective.”

Abuse of prescription painkillers has become a national concern – raising alarms among public health experts, policymakers and law enforcement officials. According to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, almost 19,000 people died from prescription painkiller overdoses in 2014, the most recent year for which data are available.

Previous research suggested that as much as 80 percent of opioids are prescribed by a small subset of medical professionals. But the authors of this research letter provide a nuanced assessment. They found that 57 percent of these prescriptions are filed by 10 percent of doctors, nurse practitioners, physicians’ assistants and dentists.

That figure demonstrates that patterns for opioid prescriptions are consistent with those for other medications, even ones that aren’t commonly abused. Generally, 10 percent of doctors are responsible for 63 percent of medical prescriptions overall.

That’s noteworthy, Chen said. It suggests that there aren’t a few errant or villainous doctors single-handedly fueling the opioid crisis. Instead, the frequency of doctors who prescribe these painkillers is almost the same as that of doctors who recommend any kind of medicine.

Whenever you look at any medication trend, the top prescribers will account for more than other people, he said. But if a few doctors were driving the opioid crisis, he said, you’d see a smaller proportion of them responsible for a larger amount of drugs compared to other medication.

“What this told us is opioids aren’t special in any way,” Chen said.

That’s why public health initiatives intending to address prescription drug abuse needs to account for all doctors, he said.

That kind of systematic approach is essential, said Dr. Caleb Alexander, co-director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Drug Safety and Effectiveness, who was not affiliated with the study. “We’re taking our eye off the ball if we’re focusing on a very small subset of doctors alone,” he said.

And the proportion of opioids prescribed by the top few is still a worry, he said. “Opioid prescriptions are skewed. It’s a little bit immaterial – it’s a second-order question how skewed prescribing is.”

The study also doesn’t account for the length of individual prescriptions are or their strength: whether, for instance, the prescription is for two weeks or 30 days; or 30 milligrams of a drug versus 60 milligrams. It’s possible and even likely, he said, that the 10 percent of prescribers highlighted in the JAMA study could be writing longer prescriptions and consequently fueling the drug abuse.

Alexander’s research, which isn’t yet published, analyzed pharmacy claims in Florida over a single year, finding there that 4 percent of providers made 40 percent of opioid prescriptions – a proportion that translated to 67 percent of all the drugs when accounting for the prescriptions’ sizes.

Some differences between studies are probably the result of the people being studied, Chen said. Medicare beneficiaries have diverse backgrounds in a number of ways, for instance, but skew older.

What matters, he said, is recognizing the role a number of doctors may play in getting patients easy access to opioids.

“Going after deviants, ‘pill mills’ or bogus pain clinics – it feels good to do that, because you have a villain. You feel that if you get rid of them, the problem is solved, and what we’re trying to say is, ‘I don’t think that’s going to be enough,’” Chen said. “Maybe all of us are contributing to this problem, even if we don’t realize it.”