RALEIGH, N.C. — Each time Beverly Tucker visited a nursing home or long-term care facility this fall, she brought along a rolling tote bag packed with supplies from the Durham County Board of Elections.

Boxes of face masks and face shields. Latex gloves and cleaning wipes. Hand sanitizer from Mystic Farm & Distillery, a local facility that was among the first to switch from producing liquor to hand sanitizer in the early days of the pandemic. And most important — even if they were dwarfed by the cleaning supplies — the absentee ballots and ballot request forms that Tucker would help residents complete in time for the election.

“The equipment is clearly different this year,” Tucker said. “But I’m doing whatever is possible to help people vote.”

Seniors in such facilities across the country have struggled to find safe ways to vote amid the pandemic. In North Carolina, it’s a particular challenge. The state is one of two (the other being Louisiana) where facility staffers are prohibited by law from assisting residents with voting. A 2013 voter ID law makes it a felony for staff to even sign as the witness on an absentee ballot.

That’s where community members like Tucker come in. The 66-year-old Durham resident is a member of the county’s multipartisan assistance team, often called a MAT, which helps residents in nursing homes, assisted living and other facilities complete mail-in or absentee ballots. The teams are appointed by the county board of elections and must include at least two people who have different political party affiliations or are unaffiliated. Some counties pay the teams, while others ask members to volunteer.

This year, the convergence of coronavirus concerns and the election has unexpectedly thrust team members to the front lines. They are entering some of the state’s hardest-hit sites, with nursing home residents accounting for about 40% of North Carolina’s COVID deaths, as cases continue to rise. The added risk has disrupted this crucial system in some areas. At least one county was unable to recruit a team, and members in another county have been unwilling to visit facilities with documented COVID cases.

But those who do venture inside say the risk is worth it to help people vote.

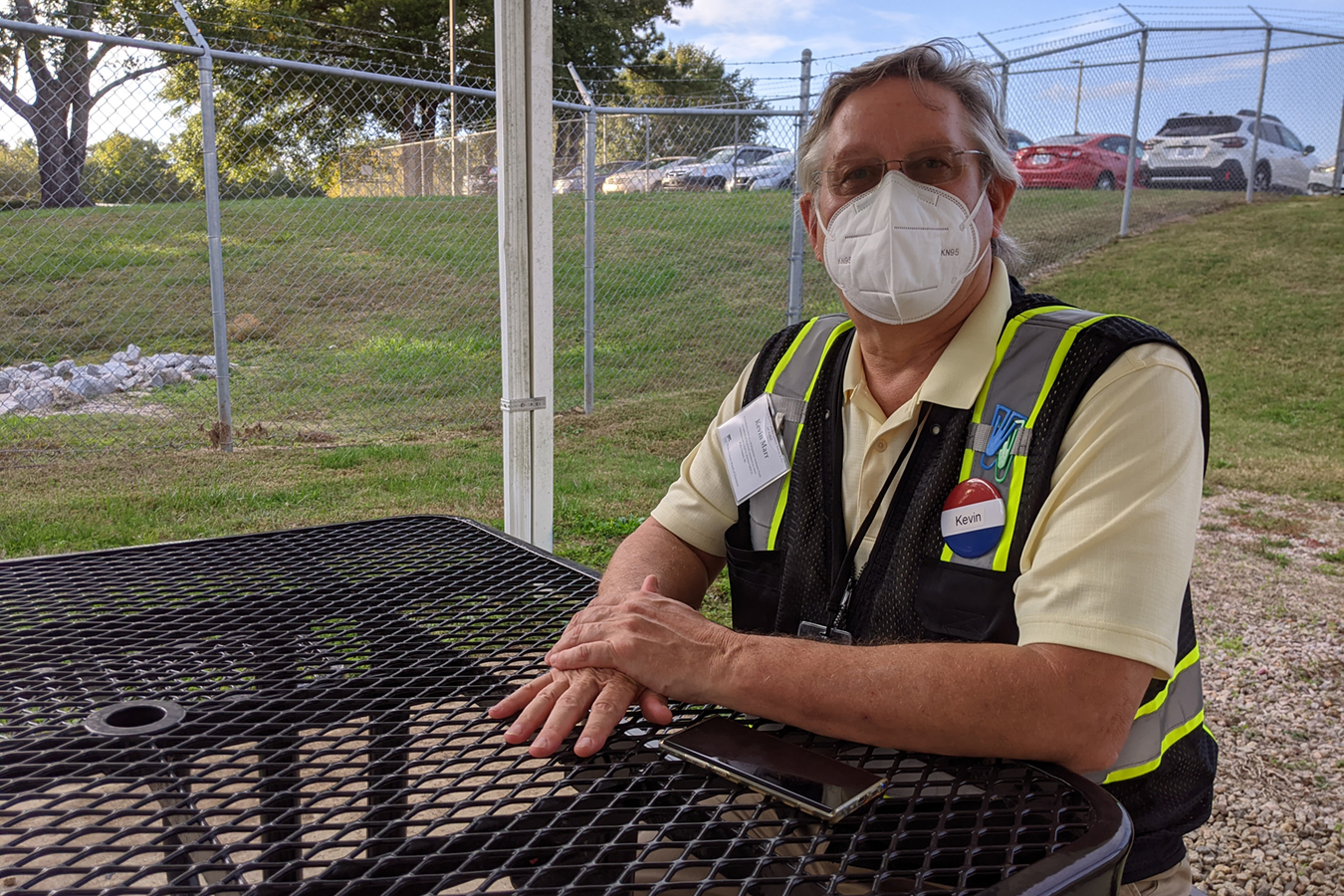

Kevin Marr, 66, has been volunteering with the voting assistance team in Wake County since 2017. He recognizes many of the residents now, even behind their masks. Although the visits are different this year, he said the residents’ enthusiasm to vote and receive their “I Voted” stickers is not. That’s what keeps him going, visiting about two facilities a day in recent weeks.

Kevin Marr has been volunteering with the voting assistance team since 2017. Although he said the visits are different this year, the residents are still eager to vote and get their “I Voted” stickers.(Aneri Pattani/KHN)

Tucker, of neighboring Durham County, has worked in public health for decades, including during the AIDS epidemic. She understood it was safer to go to residents in nursing homes and long-term care facilities than to risk them coming to polling sites with more people.

Still, when she first thought about holding voters’ hands to help them grasp a pen or sign a ballot, “I was instinctively reluctant to touch them,” she said. At the first nursing home Tucker visited, she felt anxious as a resident approached her without a mask.

But her concerns have eased over time, she said, and she simply focuses on ways to protect herself and her team. They conduct most of the visits outdoors, in the parking lot or front lawn. They put up plexiglass barriers between themselves and the voters, passing papers through an opening at the bottom. And they now carry masks for residents who may not have one.

It’s difficult to maintain social distancing when one team member is working with a resident to mark a ballot and the other is observing to ensure accuracy, but they do their best.

Foreseeing these challenges, the North Carolina Board of Elections asked the state legislature and courts earlier this year to temporarily suspend restrictions on facility staff assisting with voting. But neither request was fulfilled. A recent lawsuit contesting the restriction won accommodations for the plaintiff, who was a nursing home resident, but left the broader law intact.

At Brian Center Health and Rehabilitation in Goldsboro, administrator Julia Batts worried that MAT members would not be allowed to visit, since the facility has a designated COVID-positive unit with about a dozen residents. But when statewide visitation regulations eased in September, she eagerly reached out to them.

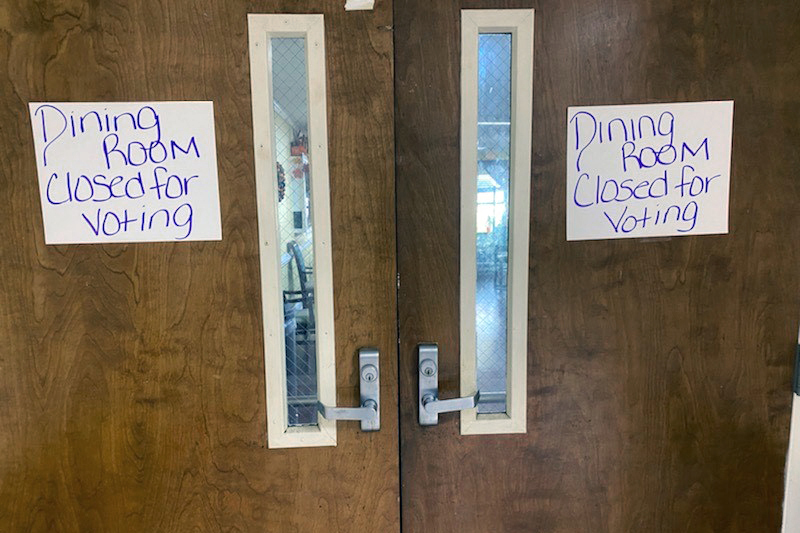

Brian Center Health and Rehabilitation in Goldsboro, North Carolina, used the dining hall of its COVID-free building as a polling place. By the end of the day, the team of volunteers helped about 20 residents vote.(Julia L. Batts)

The plan was careful and clinical. Have the team set up in the dining hall of the COVID-free building and bring in any residents who had tested negative to meet with them, two at a time, in alphabetical order.

But on the day the team arrived, it felt more like a celebration. Several women asked the staff to do their hair, and many residents “began wheeling themselves or taking their walkers to go vote,” Batts said. “They were almost racing.”

By the end of the day, the team helped about 20 residents vote. They’ll return next week to assist more residents, including new entrants who finished their two-week quarantine and those who have recovered from COVID, Batts said.

For Linda Williamson in Durham County, seeing the enthusiasm of voters reminds her of her grandparents. They took her along when they cast their first ballot in the 1960s, after African Americans won the right to vote. The then-9-year-old Williamson dressed in her Sunday best: hair ribbons and patent-leather shoes. As she watched her grandparents disappear behind the voting curtain, she couldn’t wait for it to be her turn someday.

When African Americans won the right to vote in the 1960s, Linda Williamson’s grandparents took her to the polls when they cast their first ballot. This election year, she worried that nursing home and assisted-living residents would not be able to cast a ballot. So she put her COVID fears aside, donned her PPE and visited five facilities this fall.(Aneri Pattani/KHN)

This year, she couldn’t bear to think that nursing home and assisted-living residents — many of whom likely fought for their right to vote just like her grandparents — would be robbed of that opportunity.

So Williamson, 64, put her apprehension about COVID aside, donned her face mask and gloves, and visited five facilities this fall.

To each resident she’d say, “Gosh, you picked a great day to vote.”