Dr. Thomas Bellavia transformed his traditional medical practice in Hasbrouck Heights, N.J., into a so-called medical home where patients are seen by teams of doctors and nurses. He says it has paid off in better, more coordinated care for his patients and healthier income for the nurse practitioners and physicians in his group.

Dr. Mark Holthouse took a different tack — limiting his El Dorado, Calif., clinic to 400 patients a year, and adding services such as acupuncture and fitness coaching. He said he and his team now spend more time with patients, who pay a monthly fee of $220 for a package of basic services, on top of what their insurance plans reimburse the practice.

Like Bellavia and Holthouse, many doctors are changing how they work in response to turmoil in the health care system. Both newly minted and veteran physicians face economic uncertainty amid sharpening demands from the government and insurers to improve quality while curbing costs – trends that accelerated under the 2010 health care overhaul.

The buzz, and anxiety, in the medical profession is palpable – trade magazines tout new coping strategies, doctor groups discuss the transformation of practices. Physicians are experimenting with business models and new practice techniques, hoping to find work that is both financially and personally rewarding.

“It’s not just the financial piece,” said Dr. Susan Turney, president and CEO of the Medical Group Management Association, the nation’s largest membership group of medical practice managers.

“It’s also the clinical — it’s bridging a gap so you can make the best decisions all around.”

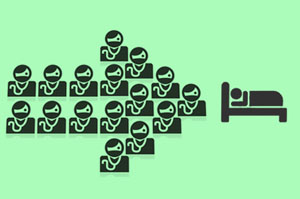

The changing landscape is reflected in the growing number of doctors who are employed by others, rather than working for themselves. Consulting firm Accenture reported in 2012 that the proportion of independently practicing physicians, working in groups or solo, will fall to 36 percent this year. One-third of those will choose a subscription-based model like Holthouse’s.

The majority, though, are seeking steadier salaries and hours: about 91,300 doctors and dentists were employed by community hospitals in 2010, according to the American Hospital Association, 30,000 more than in 1998.

But clinicians remaining independent must invest and innovate.

Bellavia’s goal of offering integrated care has cost him an estimated $300,000 since 2011 for staff training and equipment. The medical home model’s focus on preventive care includes newer technologies, like a weighing scale that reports a patient’s weight directly from home to the clinic, and reminders to patients of routine diabetes or cancer screenings. The Heights Medical Center, as the practice is called, has also expanded from two to five doctors and nurses, and hired a patient coordinator who organizes doctor visits, referrals and prescriptions.

With a medical home accreditation from the nonprofit National Committee for Quality Assurance, the Heights receives higher reimbursement payments per patient from insurance companies like Horizon Blue Cross Blue Shield of New Jersey and Aetna.

“It was all experimental,” Bellavia said. “I had to transform my staff and the way I practice. But it has paid me back considerably.”

While Bellavia figured out how to increase his insurance reimbursements, doctors like Holthouse are trying to insulate themselves from the insurance system and government budget cuts.

In 2005, Holthouse started what is sometimes called a functional medical practice – a setup that incorporates acupuncture, herbal medicines and a nutrition and exercise program. He soon found that the only way to remain profitable was to increase the number of patients treated at the practice, now called the n1Health Center for Functional Medicine — something he thought would compromise the quality of care.

“We couldn’t deliver the kind of care we wanted to with regular insurance,” he said.

With the subscription, or concierge, model that he introduced in January, Holthouse will treat about eight to 10 patients a day who pay about $2,600, in addition to the reimbursements paid by their insurance plans. By contrast, each provider at Heights Medical Center treats up to four patients per hour. Holthouse also has an herbal pharmacy with supplements and nontraditional remedies, and an acupuncturist on staff as part of his effort to offer alternative treatments along with traditional medicine.

Patients at Holthouse’s practice are still responsible for an insurance copayment for medical services that aren’t covered under the monthly fee, which accounts for basic diagnostic tests, physicals and screening. Despite the monthly costs, Holthouse said his patients supported the changes after the practice held 15 “town hall” meetings to explain the new model.

“By the time we did the conversion, one hundred percent understood why we were doing it,” he said. “They feel like they’re getting time and quality care.”

He also said that patients were spending less on medications and hospital fees, making the subscription a worthwhile investment.

Holthouse, like Bellavia, does not accept patients with Medicaid, the state-federal program for low-income people, because of the low reimbursement rates. He puts little confidence in the federal government when it comes to paying physicians fairly or streamlining the high cost of health care– one impetus for choosing the subscription-based model.

But James Doulgeris, a health care strategist at research and marketing firm HCP, said physicians who adopt innovative practices will benefit from the federal health law, because it gives financial incentives to doctors and hospitals that hold down costs while improving quality.

“It’s a 180-degree change, but physicians will have a great incentive to provide optimal care and focus on wellness,” he said.

Holthouse, however, is not convinced. “Unless you remain independent, you will have no say in what kind of medicine you practice,” he said.