ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. — As a member of the Navajo tribe, Rochelle Jake has received free care through the Indian Health Service (IHS) her entire life. The clinics took care of her asthma, allergies and eczema – chronic problems, nothing urgent.

Recently, though, she felt sharp pains in her side. Her doctor recommended an MRI and other tests she couldn’t get through IHS. To pay for it, he urged her to sign up for private insurance under the Affordable Care Act.

“I couldn’t wrap my head around it,” said Jake, 45, sitting on the porch swing of her home in Albuquerque. She didn’t think Obamacare applied to her.

“I thought [IHS] should be responsible for my health care because I am Native American.”

Tribes, health care advocates and government officials across the nation are trying to enroll as many Native Americans as possible in Obamacare, saying it offers new choices to patients and financial relief for struggling Indian hospitals and clinics.

Rochelle Jake, 45, at her home in Albuquerque, New Mexico on Monday, August 3, 2015. As a member of the Navajo tribe, Jake says she thought the Indian Health Service should be responsible for her health care, not Obamacare. (Photo by Heidi de Marco/KHN)

Under the health law, many uninsured Native Americans can get coverage under the expanded Medicaid program for low-income Americans or buy subsidized plans through insurance exchanges. That allows them to receive treatment from private doctors and hospitals rather than rely solely on government and tribal facilities.

And the coverage allows Indian health facilities –which tribal leaders say are chronically underfunded – to bill insurers for care they already provide as well as offer new services.

Advocates see the health law as a chance to reduce the health disparities that have long afflicted Native Americans, including rates of diabetes that are three times higher than the U.S. population and a life span that is four years shorter. More patients now have access to substance abuse services, mental health treatment and preventive care.

“The Affordable Care Act is starting to fill the gap between need and current resources,” said Doneg McDonough, a consultant to tribes on implementation of the health law. “And it is a huge gap that has to be filled in.”

The Indian Health Service provides care to about 2.2 million American Indians and Alaska Natives in 35 states. But the federal agency, with a fixed budget of $4.6 billion, can’t afford comprehensive services at all its far-flung facilities.

“I don’t know if you guys have all heard of this saying, ‘Don’t get sick after June because IHS runs out of funding in June?’” one Obamacare enrollment worker recently told a crowd at a Navajo agricultural business near Farmington, N.M. “So don’t get sick in July or August.”

Enrollment workers have an uphill battle, however, because many Native Americans are unfamiliar with the law and insurance or are mistrustful of the government. And because of treaties that require the U.S. to provide free health care, Native Americans can get an exemption from the health law’s mandate that everyone get insurance.

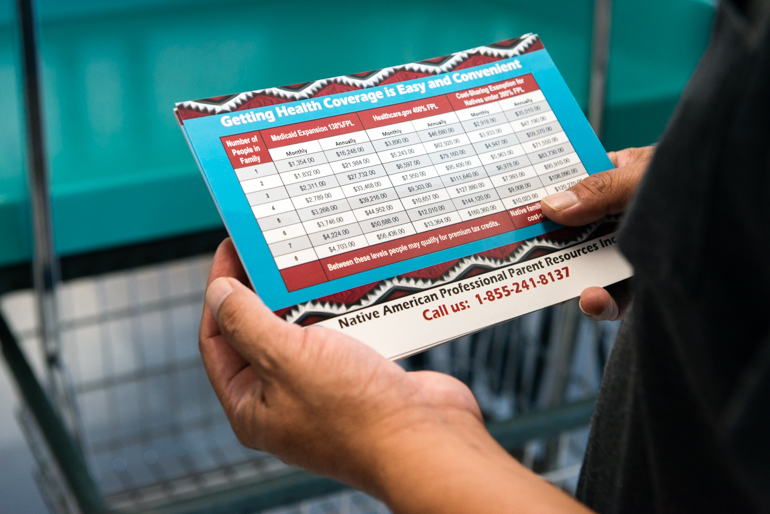

“We are just now starting to scratch the surface,” said Sonny Weahkee, outreach coordinator for Native American Professional Parent Resources, which has a contract with New Mexico to do outreach and enrollment among Native communities. “Insurance has always been available to other people, but it is brand new for us.”

Weahkee, who wears his hair in a long ponytail and greets friends with a hug, travels across the state to talk to Native Americans about Obamacare. His organization convinced Jake, despite her initial reluctance, to enroll in a plan through New Mexico’s exchange that costs about $37 a month. She can finally schedule an MRI.

“I was surprised when I was told I needed to pay,” said Jake, who works as a state tax processor. “But I got a good plan.”

Though the enrollment window for insurance exchanges has closed for most other people, Native Americans in federally-recognized tribes can sign up year-round. Weahkee meets one on one with potential enrollees where they work and live, answering questions and promoting the benefits of insurance.

At a traditional tribal feast in Santo Domingo, a small pueblo about 45 minutes from Albuquerque, he stood in front of a shaded table, handing out brochures and fans with the logo of the New Mexico exchange.

The next day, he traveled to the hilltop Navajo reservation in Shiprock, where he stopped to talk to customers at busy grocery store and a small restaurant where a handwritten menu featured mutton stew, Navajo burger and fry bread.

Weahkee also likes to visit laundromats, where people have time to kill.

At a Farmington laundromat, his colleague posted a flier with a cartoon picture of a Native American in a revealing hospital gown above the words, “Let’s get you covered.”

Weahkee spotted one woman folding clothes and launched into his spiel. “We signed up people in Jicarilla for like 32 cents a month. That’s all they paid … and they can go to any hospital.”

The woman, a Navajo tribe member, said would pass along the information to relatives. She’d already signed up for Medicaid.

Helping Hospitals Too

No reliable estimates exist on the total number of Native Americans who have enrolled in Obamacare. But tribal officials and experts around the country said Indian health facilities and contractors are already reaping the benefits. In fiscal year 2014, the Indian Health Service collected $49 million more in revenue because of patients newly insured through the Affordable Care Act, according to the agency.

In New Mexico, Leonard Thomas, acting IHS director for the Albuquerque region, said the money is helping the agency modernize aging facilities and add pharmacists, nurse practitioners and other medical staff. In addition, Thomas said IHS can now pay for more services, such as diagnostic tests and orthopedic care, if they have to be provided at outside facilities.

Before the law took effect, the agency only paid when patients’ lives were in danger. “It has increased our patients’ access to care,” Thomas said. “It really raises the bar on the type of services patients receive.”

San Juan Regional, a nonprofit community hospital in Farmington, N.M., lends space to outreach workers to sign up new enrollees. (Photo by Heidi de Marco/KHN)

Brian Garretson, director of patient financial services for the San Juan Regional Medical Center, a nonprofit community hospital in Farmington, was more than willing to lend space to outreach workers to sign up new enrollees. His hospital contracts with IHS to provide care to Native Americans but Garretson said the hospital can’t always recoup the cost from the agency.

“There are times when we get to the end of their fiscal year and they have already gone through all their money so we aren’t going to get paid,” he said.

At the Zuni Comprehensive Health Center on a reservation west of Albuquerque, a modest single-story building in a quiet neighborhood, CEO Jean Othole said she’s excited about the future. With added revenue, she plans to overhaul the obstetrics unit and expand the number of exam rooms throughout the hospital.

Still, Othole said, the hospital struggles to recruit doctors, and patients have to leave for surgeries and most emergency and specialty care. That includes women who need C-sections or who face high-risk births.

The Affordable Care Act is helping to improve services at IHS hospitals and clinics well beyond New Mexico, health officials and tribal leaders say.

In Oregon, the ability to bill insurers means tribal health facilities aren’t “running out of money as quickly,” said Jim Roberts, who serves on the Northwest Portland Indian Area Health Board. Ed Fox, health director for Port Gamble S’Klallam tribe in Washington, said added Medicaid funds were used to increase fitness programs, expand chiropractic and acupuncture services and hire community health nurses.

Fox said the tribe not only strongly encourages members to sign up, it even pays the exchange premium for some members.

Much More To Do

For all its promise, the health law has had an uneven impact on Native Americans and health centers that serve them.

Not all states chose to expand their Medicaid programs. Low-income members of a tribe who live in North Dakota can get Medicaid coverage, while others is the same tribe who live in South Dakota cannot.

And because of the way the law defines Native American, only certain tribal members are entitled to special benefits such as a restriction on out-of-pocket costs like co-pays and deductibles.

Some people are more receptive to health insurance than others. Krystal Raye, 35, who is Navajo and lives in Pinehill, said she and her entire family signed up for Medicaid. The plan pays for transportation to Albuquerque two hours away, which she said has been especially helpful since her mother is still recovering from a stroke and her brother recently had a heart attack.

Raye said a lot of Native Americans don’t realize that insurance can pay for costly health care off the reservation – which is a shame because so many are poor. “Nobody makes that much money out here,” said Raye, a home health care provider.

But Galen Martinez, a teacher who lives on the Acoma pueblo west of Albuquerque, filed for the exemption allowed to Native Americans under the law. As he cooked chicken wings at a tribal ceremonial gathering in Gallup, Martinez explained that he was borderline diabetic. He’s trying to keep healthy by running.

From his perspective, the U.S. government should fully fund Indian facilities and provide comprehensive health care to Native Americans for free. Insurance doesn’t solve the problem – even if you have it, getting from remote reservations to cities for care is burdensome, he said.

Weahkee, who is part Navajo and part Pueblo, agrees — the “U.S. signed on the dotted line” to provide free health care. But he said some services are only available from private providers, and the government’s promise “doesn’t pay for them bills once the bill collector comes calling.”

Even as outreach and enrollment continues, Weahkee and others said they are also moving onto their next goal: getting Native Americans like Margaret Thompson to use their new plans.

Thompson, a stocky Navajo woman who sells beaded necklaces, signed her husband and herself up for a private plan through the exchange. This was the first time in her life that she had insurance. The tax credits cover the entire monthly premium of $811, and she doesn’t have any co-pays or deductibles, she said.

Thompson, 59, has arthritis and diabetes and knows she needs to see a physical therapist and an eye doctor, services she hasn’t been able to get through IHS. But Thompson said she is used to the Indian Health Service and nervous about seeking out private doctors.

“I don’t know where to begin,” she said.