In the past year, new hepatitis C drugs that promise higher cure rates and fewer side effects have given hope to millions who are living with the disease. But many patients whose livers aren’t yet significantly damaged by the viral infection face a vexing reality: They’re not sick enough to qualify for the drugs that could prevent them from getting sicker.

An estimated 3 million people have hepatitis C. Faced with a cost per patient of roughly $95,000 or more for a 12-week course of treatment, many public and private insurers are restricting access to those who already have serious liver damage. Other strategies that limit access include restricting who can prescribe the drugs or requiring early proof the drug is working before continuing with treatment. In addition, many state Medicaid programs require that patients be drug and alcohol free for a period of months before they can get the hepatitis C drugs.

“Everybody is trying to figure out how best to deliver needed treatments without blowing out resources because of the cost,” says Brendan Buck, a spokesman for America’s Health Insurance Plans, a trade group. AHIP has been an outspoken critic of high prices for specialty drugs.

Insurers base their coverage decisions in part on practice guidelines issued by clinical groups such as the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD). That organization recommends giving patients with advanced liver disease priority in treatment. “Limitations of workforce and societal resources may limit the feasibility of treating all patients within a short period of time,” the organization said in a press release announcing the recommendations.

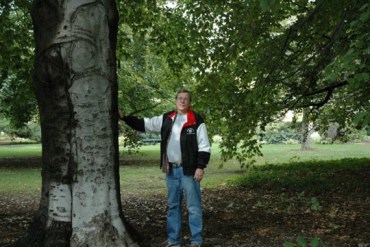

Paul Walker is one of the healthy ones. For the first time in many years, the self-employed computer systems consultant has health insurance, a silver-level HMO from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Texas for which he pays $211 a month to cover himself and his wife. (Walker had earlier investigated getting insurance through Texas’ high-risk pool but balked at the $1,200 monthly premium for two people.)

Diagnosed with hepatitis C in 1998, the 53-year-old Tyler, Texas, resident was thrilled to learn that his liver is still basically healthy. A biopsy showed only slight evidence of the fibrous scar tissue that can cripple the liver, eventually resulting in cirrhosis or liver cancer.

Many baby boomers who have hepatitis C contracted it years ago from blood transfusions at a time when blood was not screened for the virus.

Walker’s doctor prescribed Sovaldi, a pill approved by the Food and Drug Administration in December that can cure the chronic infection in 12 weeks, significantly faster than the nearly year-long course of treatment often required under older drug regimens. Sovaldi must be taken with another hepatitis C drug such as interferon, which can cause flu-like symptoms, nausea and depression and which adds to the cost. Instead of interferon, Walker’s physician prescribed Olysio, another recently approved hepatitis C drug that is popular among physicians. But its use in combination with Sovaldi for cases like Walker’s hasn’t been approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

Walker’s insurer denied his physician’s request for the drug. Walker appealed the denial and was turned down again. The insurer cited the off-label use of Olysio in its denial, but Walker says he doesn’t think an approved combination of drugs would have changed the decision. The insurer generally doesn’t approve Sovaldi for patients like Walker, whose liver fibrosis is stage “F1” on scale of F0 to F4, he said. Only patients with more severe liver damage, stage F3 or F4, are typically approved for Sovaldi.

“We are committed to providing our members access to quality, cost-effective medications,” Dan McCoy, chief medical officer for Blue Cross Blue Shield of Texas, said in a statement. “Our coverage criteria is based on clinical trial data, published literature and recommendations from a wide variety of medical specialty societies. We constantly review and update our coverage criteria as new information becomes available or new specialty drugs or treatments come to market.” The insurer didn’t respond to a request for specific coverage criteria.

In October, the FDA approved another hepatitis C drug, Harvoni, a daily pill that doesn’t have to be taken with another drug. A typical 12-week course of treatment will generally cost about the same as for Sovaldi used with another drug (unless it’s Olysio, which can push the total treatment cost to $150,000 or more). Patients like Walker might be cured in as little as eight weeks using Harvoni, however, slashing the cost by a third.

Walker says he hopes he’ll be approved for Harvoni.

“The fact that I’m only F1, that’s good,” says Walker. “But until I actually get the medication and am cured there’s going to be a lot of anxiety.”

Many baby boomers who have hepatitis C contracted it years ago from blood transfusions at a time when blood was not screened for the virus. Walker believes he got it following a childhood accident that sent him to the hospital. Others got it from contaminated needles while experimenting with injection drugs. Now, hepatitis C infections are on the rise again as a new generation of prescription opioid abusers moves from pills to injection drugs.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, up to 70 percent of people infected with the hepatitis C virus will develop chronic liver disease and up to 20 percent will eventually develop cirrhosis, a severe scarring of the liver. Up to 5 percent will develop liver cancer.

Patient advocates say that in addition to helping individual patients avoid health problems down the road or infecting others, the new drugs present an enormous public health opportunity.

“We can address hepatitis C and eradicate it,” says Ryan Clary, executive director of the National Viral Hepatitis Roundtable, an advocacy group.

Please contact Kaiser Health News to send comments or ideas for future topics for the Insuring Your Health column.