Recovery coaches and peer mentors — known in Alcoholics Anonymous as “sponsors” — have for decades helped those addicted to alcohol or drugs. Now, peer support for people with serious mental illness is becoming more common. Particularly in places like Texas, where mental health professionals are in short supply, paid peer counselors are filling a gap.

David Woodside, who has lived with bipolar and schizoaffective disorder his whole life, is getting help this way. Not long ago, he wound up in a Dallas County jail for the first time, at age 57. Woodside had gotten upset and kicked his brother.

“Nothing good happens in jail,” he said. “They don’t give you your medication.”

After his brothers, including the one he kicked, bailed him out, Woodside enrolled in an anger management class in Dallas at Metrocare, a nonprofit serving people with mental illness in North Texas.

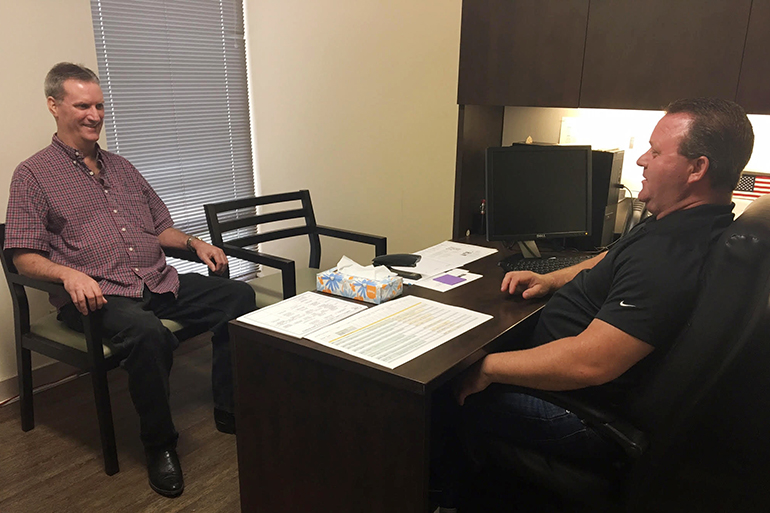

At Metrocare, Woodside started visiting David Yarborough’s office several times a week. Inside, there’s an American flag on the wall, a popcorn machine in the corner and tissues on the wooden desk.

The two Davids have much in common.

Both are fathers and have worked as electricians, and both are taking the same antipsychotic medicine. That’s because Yarborough also copes with mental illness. He’s not a volunteer — he’s a full-time, paid, peer specialist. Woodside said, for him, seeing Yarborough has been better than seeing a psychiatrist.

David Woodside visits David Yarborough’s office several times a week to get helpful coaching on how to manage the symptoms of his bipolar and schizoaffective disorder. “Dave’s been through a lot of the things I’ve been through — and vice versa,” Woodside says. (Lauren Silverman/KERA)

“[Psychiatrists] see you for about six or seven minutes,” Yarborough said. “They don’t know what’s going on with you. And Dave’s been through a lot of the things I’ve been through — and vice versa.”

Metrocare employs five trained peer specialists, including two who are part of the statewide Military Veteran Peer Network. In Texas, more than 900 people have gone through the statewide certification process provided by the nonprofit organization Via Hope. The training requires 43 hours over five days and covers topics such as ethics, effective listening, the role of peer support in recovery and using your personal story as a recovery tool. The certification is valid for two years, and a person needs to earn continuing education credits to renew their certification.

Dennis Bach, executive director of Via Hope, said most of the certified peer specialists are employed by community mental health clinics and state hospitals.

Jim Zahniser, with The Meadows Mental Health Policy Institute, said the idea of peer services has been around for decades but only recently have research studies shown how powerfully effective the approach can be.

“One of the problems with mental health is we’ve learned how to keep people ‘stable’ on their medications and get them out of the hospital. But recovery is about having a life in the community,” Zahniser said. “And peer services are often focused on those things: How do you get your life back?”

Studies show peer support specialists can do as well as traditional case managers — if not better — in keeping patients with severe mental illnesses out of psychiatric hospitals.

And, Zahniser said, when it comes to persuading people who are suspicious of doctors to seek help, peers are often the ones who can connect fastest, and get them to accept treatment.

Peer counselors historically were volunteers. But as the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services recognized their value, and more training programs were established and standardized, it became easier for hospitals and clinics to employ these specialists full time.

Texas is one of more than 35 states that finance peer services through Medicaid. There’s a severe shortage of mental health care providers in the state, so certified peer specialists bridge the treatment gap.

Joanne Spetz, a researcher of workforce issues with the Institute for Health Policy Studies at the University of California-San Francisco, says peers play a critical role in mental health teams — alongside doctors and social workers.

“When [programs] first brought in peers,” Spetz said, “[they] had to spend a lot of time with the social workers, explaining to them that we were not going to take their work and hand it off to a cheaper person — that what the peer did was complimentary, but it was different.”

(Martin Barraud/Getty Images)((Martin Barraud/Getty Images))

Peer specialist Yarborough was offered a job precisely because of his success in coping with his own mental illness and overcoming his past use of methamphetamines. When he works with clients, he can talk openly about how, decades ago, he fell into a very dark place.

“I went from the outdoorsman — fishing, yardwork, just really enjoying all that stuff — to … the guy who wants to lie in bed all day and stare out the window,” Yarborough remembers.

He started having suicidal thoughts.

“I gave my wife the key to my gun safe,” Yarborough said, “because I did not feel comfortable having access to my pistols.”

Eventually, Yarborough was diagnosed with bipolar II disorder. His condition has been stable for seven years and he has been drug- and alcohol-free for 10.

When he trained to become a peer specialist, Yarborough said, he learned to work with others while keeping a close watch on his own mental health. Every week, he helps dozens of people manage their symptoms.

His mantra? “It’s not how you fall, it’s how you get back up,” he said. “And I’ve really stuck to that concept.”

There can be a lot of stumbling with a mental illness, Yarborough noted, and having a shoulder to lean on makes the journey much smoother.

The idea of relying on peer providers in this way isn’t unique to the U.S.

“There are many parts of the world where peer specialists are being deployed in the health care system to provide mental health care interventions,” says Dr. Vikram Patel, a psychiatrist and professor of global health and social medicine at Harvard Medical School.

Patel says nearly 450 million people are affected by mental illness worldwide. In developing countries, the vast majority go untreated, he says, because psychiatrists are in such short supply. Patel has looked at the potential of peer support to help meet mental health needs in India and Pakistan.

“We’ve completed trials showing people affected by schizophrenia can be very effective in supporting other people in their own community by befriending them and giving them social support,” he said.

Patel is completing a trial that trains women in a community to help their neighbors recover — mothers suffering from depression.

He hopes Texas and other states in the U.S. continue to experiment with using peer providers, especially to serve people who are finding it difficult to get access to mental health professionals.

“Many groups experience such difficulties — for example, minorities and those who are homeless,” Patel said. “This model is one that should be adopted and integrated into the mental health care system.”

This story is part of a reporting partnership with KERA, NPR and Kaiser Health News.