Indiana expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act in 2015, adding conditions designed to appeal to the state’s conservative leadership. The federal government approved the experiment, called the Healthy Indiana Plan, or HIP 2.0, which is now up for a three-year renewal.

But a close reading of the state’s renewal application shows that misleading and inaccurate information is being used to justify extending HIP 2.0.

This is important because the initial application and expansion happened on the watch of then-governor and now Vice President Mike Pence. And Seema Verma, who is President Donald Trump’s pick to lead the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, helped design it. (Among other functions, CMS oversees all Medicaid programs.) So, states are watching to see if the approval of Indiana’s application is a bellwether for Medicaid’s future.

To get the program extended again, the Indiana Family and Social Services Administration has to prove to CMS that the experiment is working and that low-income people in the state are indeed getting access to care and using health care efficiently.

The key part of Indiana’s experiment requires low-income participants to make monthly payments. Advocates say this promotes recipients’ taking personal responsibility for their health care. But some health policy experts say the information provided by the state shows that the provision isn’t working as well as it should. Some examples:

The Claim: Most members are making regular payments to maintain coverage.

The Fact: A lot of people are missing the first payment.

The state’s application says that “over 92 percent of members continue to contribute [to their POWER accounts] throughout their enrollment.”

This claim is missing context. Here’s a primer on how HIP 2.0 works: Members can get HIP 2.0’s more complete coverage, the HIP Plus plan, by making monthly payments into a “Personal Wellness and Responsibility Account,” or POWER account.

If they don’t make the payments, there are penalties. If a recipient makes less than the federal poverty level — about $12,000 a year — they’re bumped to HIP Basic, a lower-value plan that requires copays and doesn’t include vision or dental insurance.

If a recipient is above the poverty line and misses a payment, they become locked out of coverage completely for six months.

The state’s claim that 92 percent of members make consistent payments is based on data in a report by the Lewin Group, a health policy research firm in Virginia that evaluated HIP 2.0’s first year.

But the Lewin report also says that when people sign up for HIP 2.0 they can be declared “conditionally enrolled,” which means they’re eligible but have not yet made their first payment.

According to the Lewin report, in HIP 2.0’s first year, about a third of people who were conditionally enrolled never fully joined.

“I don’t see those numbers being captured,” said Dr. David Machledt, senior policy analyst with the National Health Law Program, which advocates for low-income individuals. Machledt said the state should recalculate the figure to include those people, because it’s potentially an indicator that people are confused about how the program works or that they can’t afford the payments.

He added that the figure cited is based on the first year of HIP 2.0, and that the rate of losing coverage for missing payments has increased substantially since then.

The Claim: HIP 2.0 users check their POWER account.

The Fact: More than half of people don’t even know they have one.

The state says the POWER account is promoting personal responsibility in health care; meaning, if someone is aware of how much they are spending, they’ll choose their medical care wisely. As evidence, the state writes in its application that 40 percent of HIP Plus members “check their [POWER Account] balance at least once a month.”

Again, the state leaves out important context. According to the Lewin report, most people in HIP Plus didn’t know they had a POWER account. Of those who did, 40 percent checked their account once a month, but that’s much smaller than 40 percent of all HIP Plus members. In fact, an analysis of the numbers shows only about 19 percent of HIP Plus members reported checking the balance of their POWER account monthly.

Rather than evidence of personal responsibility, Judy Solomon, vice president for Health Policy at Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, sees evidence of confusion.

“I think that’s another really significant finding [in the Lewin report] that so far I have never seen the state come to terms with,” said Solomon.

A spokesperson for the state wrote in an e-mail that the phrase “of the members surveyed” was unintentionally omitted from the application.

The message did not address the overall concern that the statement was misleading.

The Claim: People on HIP Plus are more responsible.

The Fact: Experts say HIP Plus is just better insurance.

The application also says “HIP members who contribute [to their POWER accounts] are twice as likely to obtain primary care (31 percent to 16 percent), have better prescription drug adherence (84 percent to 67 percent), and rely less on the emergency room for routine treatment.”

Machledt said simply showing that HIP Plus members use the emergency room less frequently than HIP Basic members doesn’t tell the whole story.

“They don’t talk about the risk profile of those different groups,” Machledt said. He said people who are above the poverty line are generally less likely to frequent the ER in the first place. “There’s no evidence to me that they’ve risk-adjusted … to show that they’re comparing apples to apples,” he said.

Indiana argues that the higher levels of primary care use and drug adherence for those making POWER account payments “confirms the principle of personal responsibility.”

But Solomon said the differences in behaviors simply confirm something else: Those who pay their POWER account have better insurance. HIP Plus makes it easier for people to access primary care and to adhere to their prescription drug regimens, Solomon said.

“The policy for people in HIP Plus is that they get a three-month supply of drugs, and can even use mail order, without any copays,” she said. Meanwhile, people in HIP Basic have to pay copays and are limited to a one-month supply of drugs.

Solomon said getting less primary care and relying on the ER for health crises is worse for patients and could also mean higher costs. “You have large numbers of people that are not getting care in the right place at the right time, and not maintaining adherence to prescription drug regimens.”

The Claim: HIP 2.0 is meeting its enrollment projections.

The Fact: No, it isn’t.

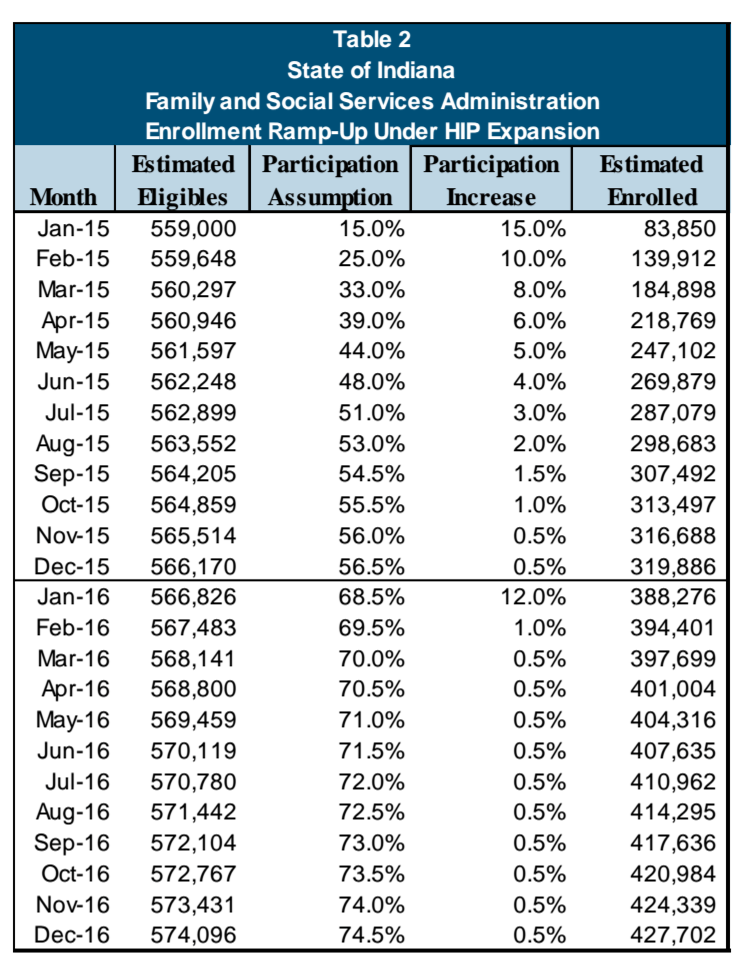

Enrollment projections for HIP 2.0 submitted to CMS in 2014. (Healthy Indiana Plan Expansion Proposal/FSSA)

The state’s application reads “HIP has continued to meet its enrollment goals with over 394,000 individuals fully enrolled in HIP as of December 1, 2016.”

But the state isn’t meeting its enrollment goals. According to a chart published in 2014 in Indiana’s original proposal for HIP 2.0, its enrollment goal for December of 2016 was higher: 424,339. (The chart is off by a month, because the state started HIP 2.0 a month later than planned, so the actual projection for December 2016 appears on the line for November 2016.)

The most recent enrollment report shows 403,142 HIP members in January 2017, short of the state’s projection of 427,702.

The Claim: The survey shows people like HIP 2.0

The Fact: The survey’s data and methodology are unreliable.

There’s reason to doubt the survey results that underlie much of the Lewin report, according to Dr. Leighton Ku, director of the Center for Health Policy Research at the Milken Institute School of Public Health at George Washington University.

“They were not using what would generally be considered best practices in their survey methodology,” Ku said.

Ku said the methodology available to the public is vague. From the information provided, he said, there are multiple ways that bias could have been introduced into the survey results used in the Lewin report. For one thing, the sample sizes of the survey were too small to draw accurate conclusions, Ku said, and the data was analyzed using “not an optimal method.”

Ku said that the results are not displayed in a scientific manner and that it appears the survey and analysis were done in a hurry. “You would not, as a survey researcher, have great confidence in the results that they show,” he said.

Conclusion

As Indiana looks to extend HIP 2.0, health policy experts say it’s important to get an accurate picture of how well the program is working. Requiring POWER account payments was key to making the program a reality in Indiana, but they say a more traditional Medicaid expansion — one that does not require monthly payments and six-month lockouts — is a better option.

Dr. Jennifer Walthall heads the Indiana Family and Social Services Administration, the government agency that runs HIP 2.0. She said that in order to comment on discrepancies between the state’s extension application and the Lewin report, “I would have to go back and look at the way that these data were reported.” She continued, “I’m happy to look into that and get that for you.”

In a separate prepared statement, the agency noted that the state “has made significant achievements” on HIP 2.0’s stated goals and that it looks forward “to continuing to build on these successes with future versions of HIP. … The analysis of this program is constant and ongoing and includes continuous conversation with our federal partners to discuss all aspects of the proposed waiver as well as program outcomes.”

If the application does not go forward, the state could choose to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act without any special provisions, or not accept the expansion at all. The federal government welcomes public comment on Indiana’s application until March 17.

This story is part of a partnership that includes WFYI, Side Effects Public Media, NPR and Kaiser Health News.