McALLEN, Texas – Sanjuanita Espinoza, 55, doesn’t seem like a gold mine for private insurers. She’s disabled, has high blood pressure and has no family to help with her care.

Yet, to some Texas insurers, she is an opportunity. In August, the state picked five health plans in South Texas to oversee care for people such as Espinoza who are enrolled in Medicaid, the state-federal program for the poor. This scenario is playing out across the country as states increasingly turn to private insurers to rein in the cost of Medicaid.

But Medicaid managed care is a risky business. Many new enrollees are older and sicker than the people health plans typically cover. The political environment is fierce, and insurers face resistance from doctors, hospitals and perhaps patients.

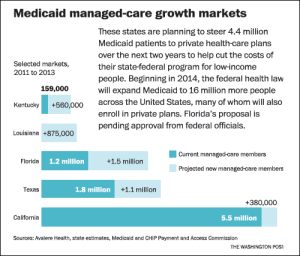

The federal health law calls for a huge expansion of the Medicaid program in 2014 – a potential bonanza for insurers if the law survives court challenges and opposition by Republican contenders for the White House. The expansion will add 16 million enrollees, mostly in private plans, bringing the total nationwide to about 65 million and raising the stakes for controlling costs.

As budgetary pressure rises, states are increasingly passing it on to private plans. Plans typically get a monthly sum to cover a patient’s health costs and try to save by cutting wasteful spending, such as an expensive emergency room visit when a family doctor would do.

“There is a lot of waste in the system, but it’s not something that you just flip a switch and it all goes away,” said Steve Zaharuk, a Moody’s Investors Services analyst. “There’s always the risk that, no matter how good you are, this is still a political game.”

Even so, insurers are willing to gamble, given the potential money to be made. Enrollees such as Espinoza yield on average $7 a month profit, financial analysts estimate. The margin is small, but it will add up quickly as managed care spreads. With the expansion of Medicaid managed care underway in at least 20 states and the surge of enrollment in 2014, insurers expect $60 billion in new annual revenues.

Proving ground

The Rio Grande Valley, where insurers stand to gain 425,000 new Medicaid enrollees beginning in March, could be a proving ground for the managed-care industry. Texas wants to cut its Medicaid bill there by $290 million over two years. But to accomplish that, and make money for themselves, insurers must overcome obstacles of politics, poverty and culture, including language barriers and resistance from health providers.

If plans succeed here, said John Littel, an executive vice president at Amerigroup, a leading Medicaid health plan operator, “it will show that you can bring managed care in and improve [health care] anywhere.” Amerigroup leads the Texas Medicaid market and won new business elsewhere in the state this month, but not in the valley.

The McAllen area is an epicenter of high government health spending. A widely circulated 2009 New Yorker magazine piece showed Medicare, the federal health program for seniors, spends twice the national average per patient here. Older and disabled Medicaid patients, such as Espinoza, cost the state more here than in any populated area, $15,311 a year on average.

One reason is that “Medicaid in the valley is more than a safety net,” said deSaussure Trevino, a nurse who administers a two-doctor physician practice. It’s an economic engine that covers nearly 40 percent of the insured population, underwriting doctors’ practices and hospitals and fueling home-care companies and other services plans could struggle to control.

Elected officials, lobbied by doctors and hospitals, barred Medicaid managed-care from several counties beginning in 2003, even as it spread elsewhere in Texas. Lawmakers broke the embargo in June, responding to an 18-month lobbying campaign by insurers, the New Yorker article fallout, which focused lawmakers attention on the area’s high costs, and a two-year state

budget deficit totaling as much as $27 billion.

Gerardo (Jerry) Casas and Sanjuanita Espinosa relax during a recreational time at the adult day care center Home Away from Home in Penitas, Texas. (Photo by Delcia Lopez/AP)

?”Our Medicaid population and the accompanying financial burden are growing as we speak, and, in 2014, Obamacare will cause them to explode,” Gov. Rick Perry said in a February speech. Perry, a Republican presidential candidate, publicly contemplated ending Medicaid in Texas last year. He opposes the health law – though Washington would pick up most of the tab for expanding Medicaid – for putting Texas “on a collision course with bankruptcy.”

“The state was looking for savings in every corner,” said state Sen. Juan Hinojosa, a McAllen Democrat who is vice chairman of the finance committee and an ally of local doctors. “We knew we were going to get run over.” Providers surrendered, but there are early signs they are regrouping.

“People are leery,” said Steve O’Dell, regional vice president of Molina Healthcare, which won valley contracts. “They’re worried we’re going to clamp down and they’re not going to be able to practice medicine like they used to.”

“The valley’s always going to be a political struggle,” O’Dell added. “But we have to provide health care on a budget.”

Eyes on private plans

Investors see the warning signs. As it became clear Medicaid managed care would grow, stock prices surged – Amerigroup’s price doubled between early 2010 and last month. But a poor earnings report in July sunk its share price from a high of $75 that month to $47 Friday. Competitors such as Molina and Centene also fell.

Initially, “it was considered a growth story,” said Ana Gupte, a Sanford C. Bernstein & Co. analyst. But the stock prices’ plunge “has heightened the awareness of [Wall] Street of the risk.”

But states continue to turn to managed care to restrain Medicaid spending for lack of other options, said Joy Wilson, health policy director for the National Conference of State Legislatures.

California began moving 380,000 older and disabled patients into private plans in June. Louisiana debuted managed-care contracts in July, affecting 875,000 enrollees. In October, New York plans to begin moving about 1.5 million patients into managed care. Florida is negotiating with the federal government to move most of its 3 million Medicaid enrollees into private plans. One sticking point is whether limits would be enforced on how much plans can earn.

Plans do deliver savings, said Stan Rosenstein, a former California Medicaid director who advises states for the consulting firm Health Management Associates. They “can find inefficiencies in the system and do it cheaper than the state,” he said.

But when savings expectations are beyond their reach, companies sometimes retreat. WellPoint, the largest national insurer by membership, exited Connecticut and Nevada in 2009 and passed on Louisiana. An executive told Louisiana officials in a May letter their expectations “cannot be achieved” quickly.

“The business issue I look at is, can we actually deliver the results that the state expects,” Kevin Hayden, WellPoint’s top Medicaid executive, said in an interview at the time.

Plans chasing new Medicaid business run the risk of accepting unrealistically low reimbursement rates in this climate of austerity, said Les Funtleyder, a portfolio manager for Miller Tabak. “Anyone can roll out the red carpet and get everyone in Medicaid, but at what price?”

Struggles and resistance

Texas is confident of its savings projections for the valley because it has had more than a decade of experience setting rates in other parts of the state, said Stephanie Goodman, a spokeswoman for the Health and Human Services Commission.

But Molina has struggled in some parts of Texas. Financial reports show that in San Antonio and Houston, where it already covers seniors and disabled people, the company lost $2 million between September and February after the state cut payments. Molina also says it is losing money in Dallas, where it began operating in February.

“The number one explanation,” Molina’s O’Dell said, “is the management of personal assistant services” delivered at patients’ homes. “It is highly fragmented, and it’s very small proprietors that do that business.”

South Texas, including the valley, spends twice as much on home care and related long-term care services as the state average: $4,791 a year per eligible Medicaid patient.

Jon Scepanski, a manager of home-care firm Apex Primary Care, said plans will wonder “how many home care companies would it really take to support the people here?” To succeed, he predicts, they’ll have to push some out of business and limit patient services.

That could spark resistance from a range of providers. Doctors Hospital at Renaissance, which depends on Medicaid for 30 percent of its billings, is ready to fight back at the legislature if insurers cut revenues, according to Dr. Carlos Cardenas, its chairman. A political force, Doctors Hospital helped raise $275,000 for Perry and $225,000 for Lt. Gov. David Dewhurst since 2006 as it battled to keep managed care out of the valley.

Patients are also nervous. Espinoza, the disabled patient struggling to make ends meet, worries plans might limit her choice of doctors or cut the $28 a day Medicaid pays for her to attend the Home Away From Home Adult Daycare in Penitas, where on a recent day seniors gathered to play bingo under a canopy of brightly colored streamers.

“I don’t like being told what to do,” she said.