Updated at 11:00 a.m. on May 24.

With no debate, and a quick call of the ayes and nays, the Massachusetts Senate approved a requirement last week that all doctors and nurses talk to dying patients about their end-of-life options.

The measure was included in a sweeping health care costs bill that the House expects to consider early next month.

In the Senate, no one raised any objections to amendment no. 121, “Palliative Care Awareness.” It says that physicians and nurses in Massachusetts must talk to terminally ill patients about their end of life options, their risks and benefits and how best to manage their symptoms and pain.

“The question comes on adoption of the amendment,” said Senate President Therese, without pause, barely glancing up. “All those in favor say Aye, opposed No, the Ayes have it, the amendment is adopted,” continued Murray.

Almost three years ago, Sarah Palin claimed that such counseling could turn into death panels.

“I picture it as a panel of bureaucrats deciding who will receive that care based on someone’s subjective judgement of their years left of productive life,” Palin told radio host Sean Hannity. “That’s a cruel and evil way of allowing Americans to receive the health care coverage that they want.”

In Massachusetts, end-of-life counseling advocates say they won’t let Palin’s interpretation derail their mission.

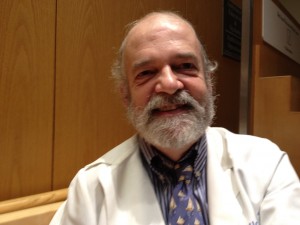

“The national controversy about death panels — what AARP called lies about death panels — is completely misguided,” said Dr. Lachlan Forrow, who directs ethics and palliative care programs at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. “In Massachusetts we can unite and show how to do it right.”

Forrow chaired an expert panel on end-of-life care that wrapped up last year. The Senate amendment is a first step toward filling the panel’s recommendations. Forrow says there’s widespread agreement in Massachusetts that to make sure patients get the care they want they must be informed about their options.

To prolong life “as long it might work in the ICU might be a choice,” says Forrow. Other patients might say “I want to be at home with my family, as comfortable as possible. People need the full range of choices. That needs to be documented if they (the patients) have preferences, and it has to be respected absolutely all the time.”

The next step, Forrow says, must be to train hospital and home care staff about how to follow a patient’s wishes.

Senate Republican leaders confirm that they have no objections to this amendment and it also has the support of one of the state’s leading right-to-life groups, the Massachusetts Family Institute. But the group’s president, Kris Mineau, has one caveat.

“We do have concerns down the road that, God forbid, should the physician assisted suicide referendum pass on the ballot in November, this could open up a Pandora’s Box,” says Mineau. A question about whether to allow physician assisted suicide may go before voters in Massachusetts this fall. If approved, Mineau would oppose adding that option to the choices doctors must mention to terminally ill patients.

New York requires hospitals and physicians to offer information and counseling about palliative care to terminally ill patients. The National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization says several bills that would establish end of life counseling funded by Medicare or Social Security (Wyden/Medicare and Blumenauer on Social Security) are pending on Capitol Hill but that state action is very unusual.

Such broad support for end-of-life discussions with doctors begs the question: Why is reception for this issue so different in the Bay State?

“People in Massachusetts are smarter than everywhere else,” said Sen. Richard Moore, laughing. Moore sponsored the the end-of-life counseling amendment. “No, seriously, we approached this in the right way, bringing in people who had experience with it.”

The point, Moore said, was “not to demonize anybody in the process, and I think that’s a big part of it.”

Moore stresses that the state would not require that patients make end-of-life plans or even have the conversation if they don’t want to. Under the Senate plan, the state would consult with the Hospice and Palliative Care Federation of Massachusetts on information and guidelines for counseling patients.

This issue is only in the Senate health care costs bill right now. House leaders declined to say if they would support such an amendment when the House takes up its version of the health care cost legislation.

This post is part of a reporting partnership that includes WBUR,

![]()

and Kaiser Health News.